The Soul of a New Narrative: Another Look at Stories of Mixed Heritage

Sophfronia Scott on Passing, and Tracing the Boundaries of Prejudice in Biracial Characters

In the politically contentious days of the mid-1800s, the noted writer and abolitionist Lydia Maria Child published a short story, The Quadroons, in which a girl named Xarifa discovers her mixed-race heritage, is sold into slavery, and commits suicide after being raped by her new owner. Child ends the story with these challenging sentences: “Reader, do you complain that I have written fiction? Believe me, scenes like these are of no unfrequent occurrence at the South.”

The author meant to drive a stake into the heart of slavery, but she also brought forth with Xarifa’s death a new entity marked by its own assumptions and limitations—the trope of the tragic mulatto. The term mulatto, derived from the Spanish word for small mule, which itself is a cross between a horse and a donkey, once described a person with parents of different races.

The tragedy of the mulatto’s existence stemmed from either being exiled from white society after learning of their parentage or choosing to pass as white and making the decision to cut themselves off from their Black relatives. The gravity of these issues often left the characters feeling that they belonged nowhere, and suicide often became their final choice.

Today “mulatto” is an offensive, outdated word, and “tragic” is not the assumed outcome in a world where the likes of former president Barack Obama, Vice President Kamala Harris, and Super Bowl winning quarterback Patrick Mahomes are celebrated for all aspects of their varied heritages. But “celebrated” or even “accepted” doesn’t mean a lack of struggle—note Colin Kapernick, or Meghan Markle, the Duchess of Sussex. Society still can’t wrap its mind around “both and,” and the question “What are you?” persists.

And I do wonder about what that struggle looks like today as the word “belonging” has become the catch phrase across multiple organizations. Companies want to build a culture of belonging in the workplace. Colleges want students to feel that they belong on that school’s campus.

Belonging is, in fact, a human need. Individuals want to belong to a larger group, to feel that they are connected to a larger entity. But does that mean there will always be boundaries that must be crossed or left behind? What would it look like if we knew how to belong to ourselves first? Only telling new stories will allow us to explore the answers and perhaps provide agency to characters that had no choice before. I have sought to do this in my novel Wild, Beautiful, and Free with the mixed-race character of Jeannette Bébinn, a girl sold into slavery in the American South of the 1850s but whose fate is quite different from that of Xarifa’s.

The following works are worth noting because the journey of their mixed-race characters tells us something about ourselves and where we most want to feel at home—in our own skin. And perhaps more importantly, they make us aware of where we draw boundaries that are entirely capable of erasure—a discovery that leads to a world opening, and not doors closing.

*

Marcus Gardley, The House That Will Not Stand

Marcus Gardley’s 2014 play focuses on a “liminal moment” in Louisiana’s history when rules regarding miscegenation and slavery were sufficiently blurry enough to allow “free people of color” access to status and wealth. As the common law wife of rich landowner Lazare Albans, the mixed-race matriarch Beartrice lives such an existence in the New Orleans of 1836. But she recognizes the precarious state of her rights. When Lazare dies mysteriously, Beartrice is determined to ensure claim to her home and the inheritance of her daughters, even if she must threaten Lazare’s legal white wife to do it.

But the teenaged girls, Agnès, Maude Lynn, and Odette, fast becoming young women, have their own concerns, wanting to be loved and to grasp identities that go beyond the lightness or darkness of their skin. Agnès and Odette plot to sneak out to the annual masked ball where they might captivate white lovers of their own, not realizing what they desire is what their mother sees as akin to slavery. The family’s competing desires clash over the course of a desperate night. “Oh, you hate me now,” Beartrice says to her bewildered offspring. “But age will teach you how great was my love.”

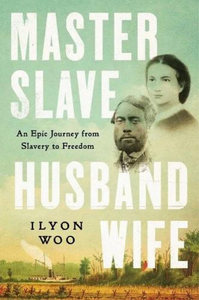

Ilyon Woo, Master Slave Husband Wife

At the age of 11, Ellen Craft, the daughter of an enslaved woman and her enslaver, a white city surveyor, was taken from her mother and presented to her white half-sister as a wedding gift. When she eventually married herself, Ellen and her husband William resolved to have their children born free.

In 1848 they devised a daring escape. Ellen, fair-skinned enough to pass for white, disguised herself as a man debilitated by illness. William pretended to be this character’s slave, and together they traveled openly, making it to freedom in Pennsylvania and later a life in Canada and then England. In England they would learn to read and write and, at long last, Ellen would give birth to free children.

Woo’s 2023 book, now a bestseller, describes the lives of the Crafts and their thrilling escape in satisfying, rich detail. But I should note that I learned of the Crafts from a book I found while shopping at a used book sale sponsored by my local library and used in my research for my novel Wild, Beautiful, and Free. The book, Runaway Slaves, published in 2004 by Greenhaven Press as part of its History Firsthand series that “explores major events in world history through eyewitness accounts” devoted ten pages to the escape of William and Ellen Craft. Their story electrified me. It felt hopeful and empowering, both elements I wanted to elevate the tale of my character Jeannette’s perilous experiences. I knew the Crafts’ escape, at least in part, would become Jeannette’s.

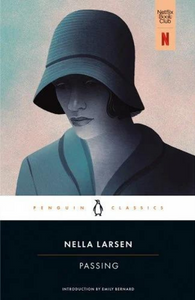

Nella Larsen, Passing

On a sweltering day in 1920s Chicago, Irene Redfield passes for white, temporarily, so she can take refuge and sip iced tea in the breezy rooftop restaurant of an upscale hotel. There she encounters a childhood friend, Clare, who, Irene learns, is passing too but not just for the afternoon. She lives her life as a white woman and has married a racist white man who doesn’t know her background.

Though the story is told from Irene’s point of view, author Larsen (herself half Black, half Danish) makes it evident that Clare suffers a loneliness she cannot shake, which makes her repeatedly seek out Irene. She even shows up unannounced to Irene’s Harlem home and infiltrates her life, much to her friend’s chagrin. Irene is irked by the attention, but at the same time she holds a grudging admiration for Clare, is curious about her life and her intentional actions taken to achieve what she wants. She begins to doubt her own choices even when Clare’s choices lead to destruction. Netflix released a film based on Larsen’s Harlem Renaissance novel in 2021.

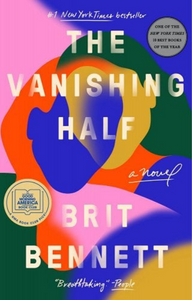

Brit Bennett, The Vanishing Half

Brit Bennett takes up the mantle of Passing and plays out its storyline across generations. Except the two characters at the heart of the novel are not childhood friends, they are sisters—and twins. Initially Desiree and Stella escape their rural Louisiana home together to make a life for themselves in New Orleans. But soon Stella realizes how much easier her life is when she pretends to be white, and she decides to make the pretend permanent by leaving Desiree behind and marrying a white man.

Like Clare in Passing, Stella feels the lonely strain of upholding her denied background. She’s also haunted from witnessing, as a girl, the death of her father at the hands of white men. But Stella refuses to give up, even when her daughter crosses paths with Desiree’s and the unacknowledged niece insists on knowing the woman who broke her mother’s heart. The argument ensues. What is identity? Who are we really? Stella insists she is the life she has lived, the life she has chosen.

James Welch, The Death of Jim Loney

This 1979 novel features the archetype of the biracial character who belongs nowhere. Jim Loney, half-white, half-Native American, is disenfranchised and lives a solitary, alcohol-soaked reality in a bleak Montana landscape despite the attentions of a caring sister who tries to will him to life. But is this because Jim can’t find a place to fit in, or because the boundaries of both heritages conspire to keep him out?

Abandoned by his mother and rejected by his white father, Jim is plagued by dreams that seem to mirror the type of vision quest he would have had as a young man in Native American traditions to help focus his life. He tries to puzzle out the images while remaining a sphinx to those around him. The direction he comes to, though, ends up having its own sad limitations.

James McBride, The Color of Water: A Black Man’s Tribute to His White Mother

Growing up in the Brooklyn projects with his 11 siblings and twice-widowed mother, McBride’s life was too chaotic to settle into the question of why their mother was so obviously white and he and his brothers and sisters were not. As a young man and a writer, he finally, through a series of interviews with his reluctant subject, pries from her the details of the family she ran away from—her strict and abusive Orthodox rabbi father, her handicapped mother, and the store they ran in a rural town in Virginia heavy with its own racial divides.

McBride crisscrosses his mother’s story with his own coming-of-age narrative in which he keenly feels that for all his determined life as a Black man, he must incorporate all the pieces his mother has left behind so that can be truly whole.

Heidi W. Durrow, The Girl Who Fell from the Sky

Preteen Rachel Morse, the daughter of a Danish woman and a Black GI, survives a family tragedy and is sent to live with her father’s family and attend a school where suddenly she must account for what she is. “There are 15 black people in the class and seven white people,” she observes. “And there’s me.”

While Durrow, of the same parentage as her character, is well aware of the trope of the doomed mixed-race character, she acknowledges the past (even naming Rachel’s mother Nella after author Larsen) and writes boldly, resolved to create a character whose life would not be defined by tragedy. “I really wanted to give her a voice to see how she might grow up,” said Durrow in an interview.

In Rachel’s journey, Durrow expresses a viewpoint which, I believe, we share: Life is a gift, likewise the struggle for identity, for love, for family. It doesn’t have to be tragic no matter how hard. Rachel, said Durrow, is “still able to be whole, ultimately, and I think ultimately triumphant.”

__________________________________

Sophfronia Scott is the author of Wild, Beautiful, and Free, available now from Lake Union Publishing.

Sophfronia Scott

Sophfronia Scott is a novelist, essayist, and leading contemplative thinker whose work has received a 2020 Artist Fellowship Grant from the Connecticut Office of the Arts. Her book The Seeker and the Monk: Everyday Conversations with Thomas Merton won the 2021 Thomas Merton “Louie” Award from the International Thomas Merton Society. She holds a BA in English from Harvard and an MFA in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Her latest book is Wild, Beautiful, and Free, a historical novel set during the Civil War. Sophfronia’s other books include Unforgivable Love, Love’s Long Line, and This Child of Faith: Raising a Spiritual Child in a Secular World, co-written with her son Tain. Sophfronia is currently the director of Alma College’s MFA in Creative Writing, a low-residency graduate program based in Alma, Michigan. She lives in Sandy Hook, Connecticut.