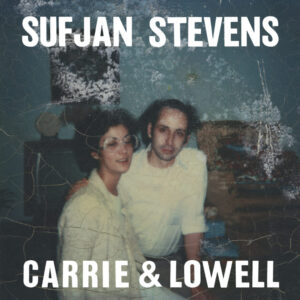

"The Songs Prove That We Were Here": Ocean Vuong on Sufjan Stevens

The Author of "The Emperor of Gladness" Considers the Life Raft of Music

When Carrie & Lowell was first released in 2015, I was still in grad school at NYU, trying to finish what would become my first book of poems, Night Sky with Exit Wounds. I remember listening to the album while walking around Greenwich Village, down 11th street towards 5th avenue, then back towards 6th via 10th street. I’d circle those blocks while the album emptied from my phone and into my body, trying to solve particular ticks and problems in my writing. I didn’t know then that Sufjan had studied Creative Writing at The New School, on that very same block fifteen years prior. That we shared this geographical and vocational space touches me deeply—especially since Sufjan’s music has been such a pivotal soundtrack to my life as a writer: his tenderness for all living things expressed through numinous lyrical softness, the songs populated by peoples of all ilk, parents, brothers, lovers, losers, criminals, ghosts, nobodies, the living and the lost. But also the careful and meticulous craft in how these songs are made: undergirded by the images and objects that prove a life has been lived fully, the detritus around the human body as we traffic through time is marked (in this album and elsewhere), not merely as texture, but as effervescent naming and expanding personhood via memory. The only other songwriter I could think of that has such fearless, even stubborn, specificity, ignoring the tired adage for songs to be simple in order to “reach” the most people, is Joni Mitchell. And like Mitchell, Stevens’ album feels carved from a space already experienced without apology or fear, that is, they feel reverent to human life with all its flaws, joys, sorrows, obsessions and triumphs. Like the best writing, it doesn’t turn away from the outcasted center.

The songs prove that we were here. They are made of air—and yet we walk on them.

“What’s the point of singing songs,” Sufjan croons in ‘Eugene,’ “if they never even hear you?” And the question sits at the heart of all written art, and is the question I’ve been asking my whole life. Strangely enough, it was ten years earlier, back in 2005, when I first heard Sufjan’s voice—in Illinois. I was 17 and it was August. The heat rose all around from the night like the exhales of tired travelers, and the crickets and treefrogs droned in the trees as I crossed the baseball field of my tenement neighborhood, toward the car parked on the far edge of the park. Despite the heat, I wore a hoodie thinking I could hide in it, that whoever was on the other side would have to burrow through it and find me. I wore my best black Levi’s 501s, as if this was some date and not a hookup set up on AIM messenger after hours scrolling on chatrooms praying I’d meet anyone near enough to touch me. My shadow, made larger than life by the headlights, crept along the gravel and fell into the shotgun window, then over his face. I opened the door and noticed his basketball shorts. Chicago Bulls. His tank top darkened at the pits, the vinegar and asphalt scent of body odor in the air, proof he had driven over an hour white-knuckling through the night. That quick moment of fixed staring, one I would come to know again and again, both of us gauging who we are, what we should be, to one another. He said he was 28 and looked it. And I hoped I was as 21 as I could muster. It was my first time doing this and, palms sweaty in the passenger, I asked if we could just talk a bit. And for some reason, after some fumbled small talk, when he mentioned he worked as a weatherman for a local station, I couldn’t do it. The idea never occurred to me, and though it made no difference—he was handsome, he was there, and I like what I like—I couldn’t bring myself to be with a weatherman, the word suddenly stripped of all sexual ethos. And in my shame, in my naïve, unknowable teenage head, I turned away, to the fields smoldering across the ways, fields I ran through only two years ago playing baseball and hop scotch, so deep in childhood it felt inconceivably vast, when I reality I was already on the cliff of it. “I’m sorry,” I said to the floor, tucking the words neatly between my white Vans, “I can’t. I just kinda can’t right now, okay? I never did this yet.” And maybe it was the fear in me trying to find a reason to back out, maybe I have an unexamined aversion to weathermen stripped to tank tops and basketball shorts, who knows.

But this is not about a botched hookup. It’s about what happened next. He rolled down the windows, put his hand on my hand and held it for a bit, then suggested we just sit for a while. Then he pressed a button on the stereo and soon the CD played and the opening track to Illinois filled the cab as the crickets hummed around us. And I started to cry, and he put his hand on my back and said “it’s alright. Hey, it’s alright, buddy. You’re fine. You’re doing fine.” And all of a sudden, I was a little brother beside a big brother in a car listening to music I couldn’t fathom could feel like it’s coming from inside my bones. “You wanna get some Dunkin Donuts?” he said after a while, and soon we drove to the drive-thru and he got me an iced coffee, encouraging me to get a shot of blueberry flavor in it—to make it “nice.” He was right—it was nice. We sat listening to more of the album, on low, while he spoke between sips of iced coffee. Then he dropped me off at the edge of the park, which by then might as well been the edge of the world. I stood, waving, as he pulled out of the lot. And I walked home across the fields of my youth, filled with a kindness I didn’t know could be afforded me, one I didn’t know I deserved. And never saw him again.

Sometimes it feels like the only time anybody is whole is when they’re gone. Something complete about not finding the pieces of us scattered across our lives. Something so clean about the memory because I can’t locate it anywhere. I have no way back to him, to that night—I don’t even know his name—no way back but the songs. And those songs would grow into Carrie and Lowell, and Sufjan’s voice would find me again just as I was finding my words. The songs prove that we were here. They are made of air—and yet we walk on them. Or better yet, as was my case that night in August 2005, it became a little boat the weatherman and I rode on. We are, I hope, somewhere both riding still.

___________________________________________

Carrie & Lowell (10th Anniversary Edition) is available via Asthmatic Kitty.

Ocean Vuong

Ocean Vuong is the author of the New York Times bestselling poetry collection Time is a Mother (Penguin Press 2022), and the New York Times bestselling novel On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous (Penguin Press 2019), which has been translated into 37 languages. A recipient of a 2019 MacArthur "Genius" Grant, he is also the author of the critically acclaimed poetry collection Night Sky with Exit Wounds, a New York Times Top 10 Book of 2016, winner of the T.S. Eliot Prize, the Whiting Award, the Thom Gunn Award, and the Forward Prize for Best First Collection. Born in Saigon, Vietnam, he currently lives in Northampton, Massachusetts and serves as a tenured Professor in the Creative Writing MFA Program at NYU.