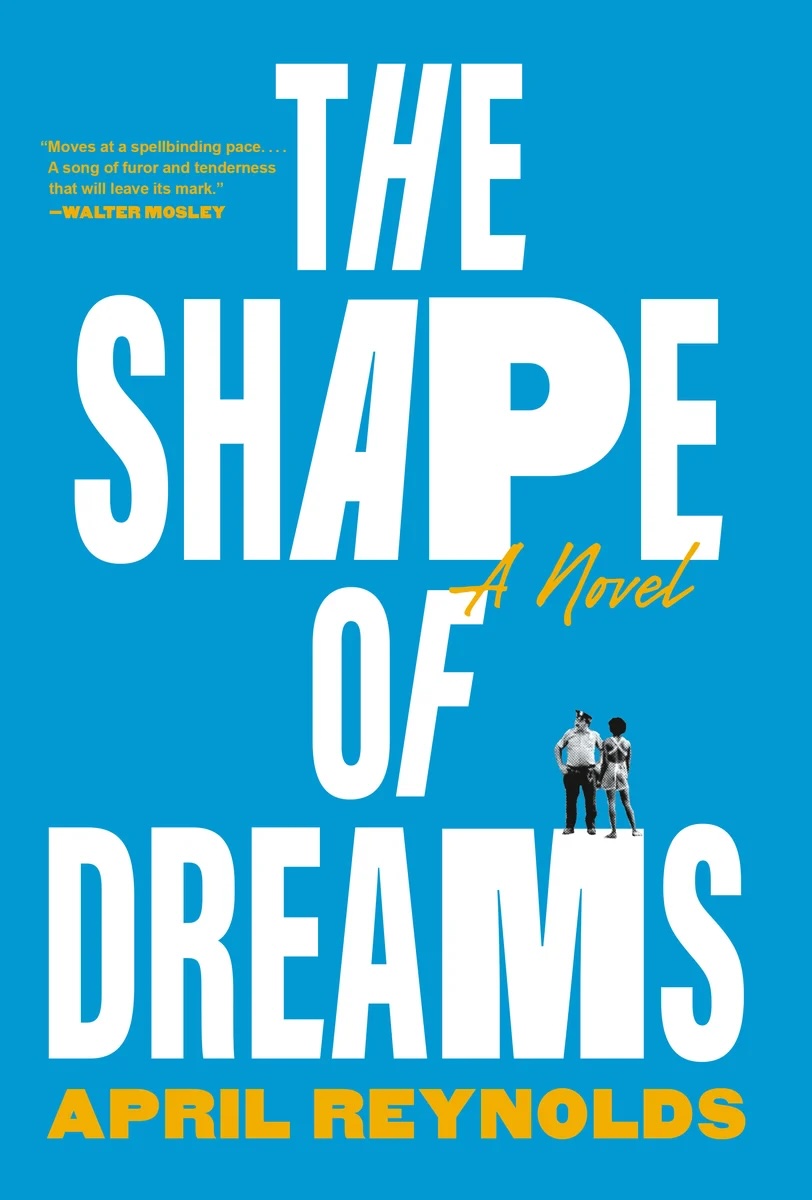

The Shape of Dreams

April Reynolds

October 1985

It was not a pretty neighborhood. There was too much hunger and lack for gorgeous architecture to take hold. Rich people were never interested in building block after stately block of brownstones. So the good people of East Harlem gussied up where they lived with what they had. Saint Agnes and Saint Thomas peeked out windows, surrounded by dumb cane and Chinese evergreen. Puerto Rican flags provided both curtains and declarations. This neighborhood was not as grand as Harlem proper, but everyone who hung their hat here knew its allure. One hundred forty-one blocks crowded in Germans, Scandinavians, the Jews, the Irish, Italians, blacks, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Dominicans, and Mexicans who wanted to make this patch of Manhattan their first stop on the island. As folks came and went, the neighborhood changed its name to fit the times—East Harlem, then Italian Harlem, then El Barrio or Spanish Harlem for those who couldn’t roll their r’s. The Italians fought and lost to Robert Moses’s wrecking whims; Puerto Ricans who could fled to Jersey for the privilege of a backyard. But black folks stayed.

When East Harlem was farm country, black people picked crops; when shantytowns sprang up, they moved in and worked the stockyards. They worshipped in storefront churches, ate arroz con pollo, and bought whiting from the fish market for breakfast. Washington, Lincoln, and Jefferson housing projects were built and black folks settled in, dreaming of moving in with their better-off cousins who lived near Lenox Avenue. And every once in a while, some black family scraped together what they could, got a loan from Grandmomma, told an Uncle Willie Boy he could have the top floor if he pitched in, and bought a building that in the seventies no one else wanted.

Twin Johnson lived in one of those buildings. Instead of an Uncle Willie Boy, she had an Uncle Manuel, and instead of being at home and in bed—it was well before dawn—Twin crouched on the sidewalk, watching her neighborhood reveal a murderous secret.

Sitting on her fat haunches and surrounded by a week’s worth of city garbage, Twin wanted to spit. Instead, she swallowed hard. Twice. The smell of Modelo beer bottles overflowing with pee filled her nose, but so did the stink of the dead boy she had just found. She could only see his face’s profile and an arm. The rest of him was concealed, tucked under corded cardboard and trash bags. Small black flies marched along his unbearably long lashes.

Their constant movement made it seem as if he were winking. Twin rummaged her memory. Did she know him? This kid wasn’t one of her cousin’s lookout boys or some little man making a score for his momma. He wasn’t one of the neighborhood’s young who dared each other to walk up to her and ask her to let him hold ten dollars for a couple of days. Twin touched his elbow and thought, Naw, he’s just one more dead black boy on Second Avenue between 109th and 110th hidden beneath garbage on a Wednesday. She ought to have been grateful that the building and its trash out front weren’t hers, but she couldn’t get the emotion off the ground.

Twin looked down the avenue to make sure no one was coming. With dawn hours away El Barrio was still dark. Its sidewalk empty. Gaylord White, Lehman, Wilson housing projects created high square mountains; the avenue made the valley; trash bags cluttered together looked like out-of-place shrubbery. Like always the East Harlem skyline took her breath away. This scenery—bodegas, funeral parlors, pizza shops—was the only kind of nature Twin knew and loved. And since she wasn’t being watched for her well-known antics as the neighborhood crazy, she peered at the kid’s half-opened mouth (he really was beautiful) and murmured what was on her heart: “Oh, sweet baby.”

What Twin wouldn’t give right now for her own hands to be her mother’s or a preacher’s. On her knees, the older woman massaged her scalp then rubbed her elbows. His eyelids still moved as if he dreamt. Back and forth. Her skin erupted in goose bumps, and Twin told herself it was because of the weather. She hung her head. She had earned her place as a bitch you don’t fuck with in El Barrio, or at least on 117th Street. But her thickened skin, along with her toughened reputation, felt supple now. This was the third dead body she had seen this year. The second one she had touched. It was only October. Not even cold yet.

In February she had found an old white woman, freckled and soft, folded into a piece of luggage. Maybe you got limber, she had thought, when you get that little and old. Twin was glad for once that she was a big woman. Otherwise some asshole could put her whole person inside a suitcase meant for weekend travel. Naked as a newborn the dead old lady was smiling, so Twin had zipped her back up and left her in the abandoned community garden underneath the tire where she had found her. Twin didn’t shake a bit when she told her uncle all about it over rice and peas. That was winter, 1985. Then at the start of spring she had walked around some Puerto Rican guy in a black-and-green tracksuit and a torn wifebeater, murdered on the footbridge at 103rd that connected Manhattan to Wards Island. Shot a bunch of times in the stomach, twice in the head, stabbed in the arm. Whatever he had done, the fucker who did him wanted to make sure he was good and dead. Twin had lifted a leg, pointed a toe, and stepped over him, careful not to step into the puddle of blood.

Stranger danger, baby girl. Those two bodies, she thought, had been the price she paid for being a roaming soul. Since she was twelve, she had a body that woke hours before dawn and wanted to be outside. Her momma had told her, “Stranger danger, baby girl. The Lord only looks after the good and the innocent, and you ain’t neither one.” But the warning never stopped her from shoving her size eleven feet in slippers, in sneakers, in combat boots, longing for outside, craving to breathe in the four a.m. chill. Fifty years later her uncle Manuel, who bossed her, her cousin, and his drug enterprise, still asked, “What you do out there, girl?” when she trudged back home with hefty bags full of odds and odder.

“Roam.”

Sometimes she would tilt her head and marvel at the only things that soared in El Barrio: the housing projects. Twin looked down the rare building alleys, stuck her hand in sandboxes, found combs with missing teeth, unopened letters from Child Services. She’d stuff them all inside her black plastic bag. It was a good way to mark the time.

In her fifty-seven years of wandering, nobody had messed with her. Twin, almost six feet tall if you included her picked-out Jheri curl, a kiss away from three hundred pounds, walked El Barrio all times of night, sober as a church, mean as a drunk. Most of her neighbors crossed the street when they saw her coming. The hustlers and the homeless nodded when she passed by. Her uncle and cousin dealt weed and crack out of a Jamaican botanical shop on 110th and Second Avenue; they had made a trap in the basement of the tenement building where they all lived. They owned the place; they thought they owned the block. “We the ones who keep you safe.” Twin would nod her head as she emptied out her private treasure from a trash bag. There was no harm in nodding. She never told her family what she really thought—that every now and again when she found a preacher and a church that would have her, it was the congregation that kept her safe and whole, even when she wasn’t sitting in the pews. Her uncle would never believe that folks would be worried they might be fucking with a follower of the Lord God, Jesus Christ Our Savior. As it was, Twin managed to smile when Uncle Manuel would warn her, “Well, keep at it and you gone find some shit you wish you didn’t.” Ain’t that the truth, she thought, looking at the curve of this beautiful dead boy’s cheek.

Twin should have stood up and left. She knew this. Calling the cops would get her nothing but a night or three in the Tombs. If she walked to a phone booth and called for help, her cousin Junior and uncle would lose it. “Don’t step in mess” was the family mantra.

She shuffled closer to the body. Twin wasn’t really moving her arm; all by itself it traveled over to the dead boy. She herself didn’t want to see his haircut; it was her hand that was interested. Maybe somebody during morning rush would stop if they saw him sprawled on the sidewalk. He’s not old or Puerto Rican; he’s one of mine. Maybe. Twin lifted three bags of trash off the kid and took a hard look. His sneakers broke her heart. Red-and-black British Knights. Every kid in the hood wanted a pair.

She wished she knew the phone number of the preacher of the last church she attended. Carl’s name perched on the tip of her tongue. Their church had burned down. He was kind and good and sometimes fierce. She should call him now and ask his advice. What am I supposed to do? How am I supposed to be, when I know some momma put a week’s salary on this kid’s feet? Some family ate a month’s worth of canned beans just so this boy could strut to school in these sneakers. The laces weren’t even dirty.

Until right now Matilda “Twin” Johnson had lived her adult life both as a nighttime roamer and as a daylight commentator. In Spanish Harlem there was always a clutter of folk standing on the sidewalk, watching and paying witness to days filled with mayhem. Stay out on an East Harlem sidewalk long enough and you could see it all: cops only came out when the coast was clear. The men in blue looked at nothing and wrote their stories in notepads. But the sidewalk commentators had stories too, riddled with escape, survival, triumph. They were shot, yes, but somehow they managed to pluck out the bullets. They were drug heads okay, but after two nights on their mothers’ couches, they were again sober. If their story was especially heartbreaking, if their fellow teller hadn’t had the time to get cleaned up and change clothes, if they had to stand before neighborhood witnesses clutching a tattered shirt together, their friends, the sidewalk commentators held off. “Look at you,” they whispered.

“Okay now. It’s okay.” Neighbors rocked victims in their arms.

Twin was one of their number. She was the one who heard hurt for what it really was, then laughed the loudest. She was the one who had the gall to curse at the violence of gangsters, whose spoken wisdom was so sharp that after her sentences you could see the bone. For almost fifty years she had listened to the story of every slap and punch that happened from 125th to 96th Streets east of Central Park. But never had she been on the other side—the somebody swaying in tatters, the chump running for their life. If she could just wait for daylight and the morning commute, some good citizen in the hood would do the right thing, call in about the body. Right? Twin looked at the pay phone, then down at the dead boy. She heaved herself to her feet and rummaged in her pockets for change.

It took fifty-five minutes for an ambulance to arrive, and then the police showed up ten minutes after that. The hood-wise Twin knew it would take forever for the cops to get there—it always took forever for the police to show up—but still she was surprised at how angry she got from waiting. Twice she almost left. But the dead kid’s eyes held her to the corner of 110th. When the paramedics finally showed, looking fully caffeinated yet bored, she learned two lessons. One, she couldn’t tell who was the Irish cop or the Italian one when they all wore the same uniform, and two, there’s a difference between telling a story after the fact and living within one. The paramedics put on gloves and face masks, and Twin’s heart lurched when they lifted the boy from the sidewalk. She expected the body to be a cardboard of rigor mortis. But that didn’t happen. His body was as limber as laundry.

The morning commuters arrived and parked themselves in front of the police tape. “Yo, that’s a kid, man.”

“He dead? For real?” The bystanders grew in number. Six people, then a dozen more joined them. “What’s up? What’s happening?” While the paramedics tried to decide whether to walk around or step over the stinking trash, a neighborhood’s shock began to bloat. Forty neighbors found themselves asking the same questions: “How long this little boy been out here? Who done this? Who is he?” The ambulance moved to the corner so the paramedics didn’t have to climb over the heaps of garbage. The three cops who showed up weaved through the crowd trying to find the somebody who made the phone call. Twin waved at them, and finally the police spotted her hiding in plain sight, standing beside her neighbors. “Here they come, Twin,” a guy said.

“Ma’am, you found the body?” The police hadn’t surrounded her, not with Twin’s back against the police tape, but it felt like it. The mustached cop stood on her left. She turned her head, her normally sleepy big eyes wide-awake, and looked him in the eye. “Ma’am, what time did you find the body?”

The truth burped out of her mouth, “I don’t know. Morning. Early.” Her heart fluttered.

“Your name.”

“Twin.”

“Your real name.”

Twin felt a sharp humiliation. Hadn’t she scolded men, women, and children who stumbled over their own names when saying it aloud to some authority figure? Hadn’t she admonished those who had aw-shucked the police that she would never cower? Where was that dreamt-up woman? Twin could hear her neighbors grousing but unable to swallow their anger and spit out her own. “Y’all can’t throw a sheet over that little man?” she said.

“What’s your real name?”

She hadn’t known this would happen, how her heart would tilt and her stomach and bladder join in on the fun. Her mouth was so dry. “Twin. Matilda ‘Twin’ Johnson,” Twin said. The cops took a step too close. The one in front of her, the one without the mustache, reached out to touch her elbow and for no reason at all stopped himself. His arrested move gave Twin courage.

“Step back,” she said.

“Excuse me?”

“You heard me.”

“I think you need to come over to the precinct. Answer some questions.”

“Naw, man. I ain’t doing that.”

The cop in front of her touched her wrist, the mustached one clamped a hand on her shoulder, and the one to her right grabbed her sleeve.

“Yo, don’t touch me. I mean it.” Twin hoped her neighbors would have her back, but it was clear their attention was fractured. Dressed for work—janitor jumpers, nurse’s aide tunics, checkered chef pants—their jobs beckoned to them to get going, but most of them were still looking at the dead boy who still hadn’t been covered with a sheet, whose new shoes in the morning sun look like their hard work. “You don’t got to handle him like that,” she said.

“Yo, respect the little man,” one in the cluster said. “Throw a sheet over him.”

“How long he been out here?”

“Yo, who did this to the little man?”

The crowd’s questions and comments began to get loud, and all at once they realized nothing held them back but flimsy yellow tape. “Let’s get back to the house,” the mustached cop said and pushed down on Twin’s shoulder, pulling her toward the police car. She wanted to ask a question of her own, one that she had wondered about before the paramedics, the police, or even her neighbors came.

A question that would answer a neighborhood’s anger.

Nothing came to mind.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Shape of Dreams by April Reynolds. Copyright © 2026 by April Reynolds. Published by arrangement with Alfred A Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Lit Hub Excerpts

An excerpt every day, brought to you by Literary Hub.