There once was a little boy who lived on a farm. Every morning he woke up, ate an egg-in-a-hole made with eggs from his own chickens, and watched his mother brew coffee in her faded nightshirt. Sometimes, after his father emerged from the bathroom holding the newspaper, the little boy would watch him slip a hand up her shirt as his mother peeped with surprise, like a stuck chick. After breakfast, the little boy would go and visit the laying hens, as it was his job to collect their eggs and give them food and water. The king of the flock was named Mr. Flash, and as the only rooster, he felt very important and protective of his hens. Every morning, Mr. Flash would fluff his tail feathers, crow at the top of his lungs, and—usually while the boy wasn’t watching but occasionally when he was—fuck a layer, even though she squirmed to get away, just like nature intended.

The boy wasn’t necessarily fond of Mr. Flash, but the rooster provided entertainment and a musicality that set the mood, except when the little boy’s sister was napping outside, and his mother shouted, “Goddamnit!” and raced to check underneath the blanket she’d thrown over the stroller to keep her little parrot from waking up and talking. Mr. Flash, despite his regular vulgarity with the hens, did his due diligence keeping order, and on a few occasions he even successfully fought off the neighborhood fox, coming to try his luck at a free lunch. So the little boy’s family accepted the fowl’s patriarchal benevolence and continued to provide him with food, water, bedding, and all the other demands of a responsible animal husband.

Then, one day, Mr. Flash woke the little boy and his family early with a god-awful crowing, louder than ever before and incessant, as if to announce a change of heart. For Mr. Flash began to show aggressive behavior toward his benefactors, even daring to attack the little boy while he was filling the feed dish and collecting the morning eggs. This was, of course, frightening, though at first the little boy gave the rooster the benefit of the doubt. He would approach Mr. Flash diplomatically with ripe rosehips, only to be lunged at and chased until the boy hurdled over the coop’s perimeter fence. Finally the little boy abandoned the treats and resorted to wielding a pine branch as a shield every morning, waving it around desperately to protect himself from Mr. Flash’s daggerlike spurs. After nearly a week, the little boy divulged the violence of his mornings to his mother, who was disturbed and who recounted the story to the little boy’s father that evening when he returned home from work. And so later that night, while the little boy was sleeping, his father went out with a .22 and killed Mr. Flash, throwing his body into the woods.

The next morning the little boy woke up as usual, came downstairs, and watched his mother make his egg-in-a-hole in her faded nightshirt. He saw his father pour his mother a cup of coffee and give her a loving pat. And then he noticed something different: the rooster hadn’t crowed. And when he went outside after breakfast, pine shield in hand, Mr. Flash was nowhere to be seen. The little boy thought this was weird and went inside to tell his father, who was reading the newspaper at the breakfast table, toast hanging from his mouth. His parents followed the little boy to the coop, and agreed that Mr. Flash was missing.

“That’s odd,” said his father.

“That’s strange,” said his mother. “Maybe the fox got him.”

The fox. Of course! The little boy was sure it was the fox. In fact, he had heard a scuffle outside the night before, as he was falling asleep. That devil. He had finally gotten what he had been wanting. Still, the little boy was sure that Mr. Flash had been eaten while bravely trying to save the layers, so the little boy could still have his fresh eggs for breakfast every morning. (It was one thing to be murdered, and quite another to die a hero.)

Later that day, after the little boy had safely collected the eggs from the henhouse with no fear of injury, he went on a walk with his mother and baby sister down the long dirt driveway to the mailbox. On the way, the little boy noticed a pile of poop in the center of the lane. He ran ahead to investigate. Sure enough, it was still warm; the boy let his hand hover over the pile without touching it. He picked up a stick from the side of the road and began poking at the poop, breaking it apart to inspect its contents. He saw seeds, some grass, and a few whole half-ripe blackberries. But then, there it was. Right in the middle of the biggest poop was a beak! The boy was triumphant—the fox had done it, and shat out proof.

__________________________________

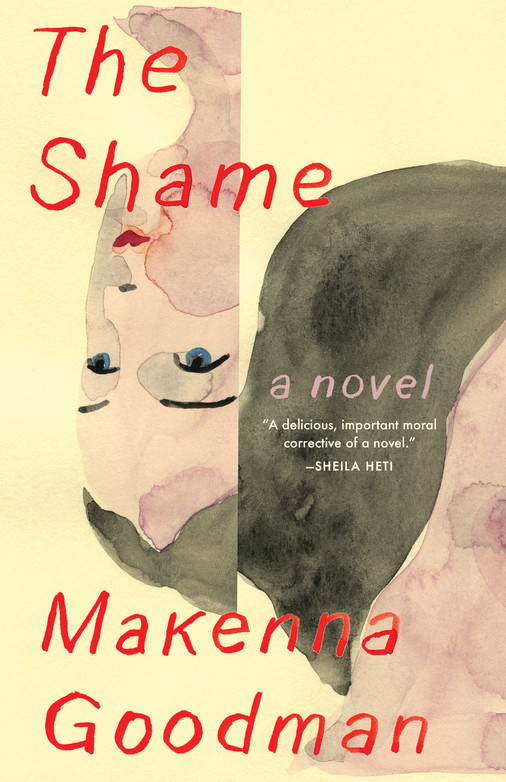

From The Shame by Makenna Goodman (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2020). Copyright © 2020 by

Makenna Goodman. Reprinted with permission from Milkweed Editions.