The Secrets and Silences of The Golden Bowl

Dinitia Smith on Henry James’s Difficult, Powerful Final Novel

The Golden Bowl is a novel about secrets, about what happens to an immensely wealthy family when its secrets begin to rise to the surface. It is James’s most difficult work, an interweaving of filaments of words and sentences, luring the reader on as he begins to sense the eroticism and cruelty embedded in it. The secrets in James’s novel are made more awful because they are never explicitly defined, the people often silent, mirroring the book’s atmosphere of concealment and secrecy.

Typical of James’s “Late Style,” the book has a muffled quality, its characters moving from grand estate to grand estate—(no one seems to have a job)—their exquisite manners veiling their actions, none of them speaking the truth. One of its pleasures for the modern reader is that James takes us back into a world that no longer exists, a 19th Century world of grand estates and formal gardens in which the characters enact their desires and their lies.

James’s style became increasingly complicated throughout his career. In The Golden Bowl, his last complete novel, the complexity reached its apogee. Gone are the typical conventions of the Victorian novel epitomized by Dickens—the scene fully described, people speaking more or less in full sentences, like actors on the stage. In the Victorian novel, the characters are known for what they look like and what they say. James’s characters are known through the ins and outs and digressions of their consciousnesses. The reader sees the truth of his inner life, reflected back at him from the page. James’s style has been called a pre-cursor of modernism and it reverberated through succeeding generations of writers, from Edith Wharton, to Joseph Conrad, to Ezra Pound and others who took their cue from him, delving into their subjects’ minds.

People in The Golden Bowl often speak in partial sentences, not in the set speeches and complete paragraphs of James’s predecessors. Almost for the first time in the development of the novel, the reader recognizes the reality of his own language, its fits and starts, its hesitations. James understood that when confronted with the unthinkable, people often cannot find the words to express it, that unfinished utterances convey far more effectively the horror of the situation, leaving the reader to wonder about its worst possibilities.

The story of The Golden Bowl is thus: Adam Verver is a widower and an industrialist from the newly-rich robber baron class of late 19th Century America—his hometown fittingly called American City. Like many robber barons and their descendants he is an art collector, a god-like figure, inscrutable, ruling over his empire with quiet power. His daughter, Maggie, to whom he is extremely close, is an innocent, engaged to an impoverished Italian prince, Amerigo, in a marriage arranged by the busybody Mrs. Assingham, whose actions propel the plot. Amerigo, in the tradition of the Gilded Age, marries partly to better his fortunes, and in exchange, will bestow upon the newly-rich Ververs the cachet of royalty

Unbeknownst to Maggie, her future husband had an affair with her childhood friend, Charlotte. They couldn’t marry because neither had any money. Just as the marriage is about to take place, Charlotte comes on the scene again. He “saw her in her light … like a lamp she was holding aloft for his benefit and his pleasure. It showed him everything—above all her presence in the world, so closely, so irretrievably contemporaneous with his own: a sharp, sharp fact, sharper during these instants than any other at all, even than that or his marriage.” With its endless clauses, its elaborate structure, it is a typically complicated James sentence, but buried amidst its labyrinthine prose, the words “light” and “irretrievably,” the repetition of “sharper,” stand out even more and have more impact.

Amerigo and Charlotte shop for a wedding present for Maggie. Charlotte almost buys a gilded crystal bowl, but the Prince notices a crack in it. Perhaps seeing it as a sign that his forthcoming marriage is doomed, he stops her.

The marriage goes forward, and Amerigo and Maggie have a son. Maggie begins to sense the attraction between her husband and Charlotte, “She had but wanted to get nearer, nearer to something that she couldn’t, that she wouldn’t, even to herself, describe.” Typically, James never reveals what that “something” is.

The awareness fills Maggie with “the horror of the thing hideously behind, behind so much trusted, so much pretended nobleness, cleverness, tenderness.” Again, James doesn’t tell us what “the thing” is, further drawing us in to wonder about its dimensions, what Maggie will do. As the novelist John Bayley once wrote, Henry James “equates love with the abnegation of knowledge, the readiness not to know.”

In an effort to separate Charlotte and the prince, Maggie encourages a relationship between her father and Charlotte and the two eventually marry.

One rainy day, Charlotte arrives at the Prince’s house. Maggie and the child are out. “They were silent at first,” James writes, “only facing and faced, only grasping and grasped.” Then, they kiss, “with a violence that had sighed itself the next moment to the longest and deepest of stillness they passionately sealed their pledge.” The reader is made to infer from the long sentences that follow the sexual encounter that follows.

How can Adam Verver, not see what is happening before his eyes, his wife having an affair with his son-in-law? Adam tells his daughter that he has never been jealous. Maggie’s only gives her father “a look that seemed to tell of things she couldn’t speak.” Again, the characters never say what they know and mean.

Charlotte desperate to discover what Maggie and Adam, upon whom everyone’s fortunes depend, know about her relationship with Amerigo, confronts Maggie. The few words they utter are interpolated with Maggie’s inner thoughts. “She couldn’t say yes, but she didn’t say no.”

The moment of truth comes when Maggie herself buys the golden bowl with its crack. The shopkeeper remembers that the prince and Charlotte had almost bought it, thinking they were “a couple.”

At this point, Maggie and her father, carrying the weight of their knowledge—still left unspoken between them—engage in a scheme of Machiavellian cunning. Adam announces that he is taking Charlotte back to America, a country she hates, to build a museum, separating her forever from her prince and Maggie will keep him. She and her father, with their exquisite manners, have done something monstrous, imprisoning their spouses in marriages with people they do not love.

Charlotte is left to wonder what the man with whom she is to live out her life, knows about the affair. Emily never tells the Prince what she knows, leaving him to wonder if one day the words will burst out of her. Will she employ her rich family’s legal resources to separate him from his child? At the end, the Prince approaches Maggie. “’I see nothing but you,’” he says. “And the truth of it had with this force after a moment so strangely lighted his eyes that as for pity and dread of them she buried her own in his breast.” Sentences like these make The Golden Bowl a difficult work.

The Golden Bowl is also a novel about the power of silence, another element of its difficulty. Maggie and her father never define the exact nature of the punishment, its foreseen consequences. James leaves us on edge.

The reader is left to imagine for himself all the terrible ways that Charlotte and Amerigo’s lives will be like.

This silence makes The Golden Bowl a difficult work. In his essay, “The Art of the Novel,” James called it “the power to guess the unseen from the seen.” Or, the power to guess that which is unsaid. The reader’s imagination is activated. The onus is on him.

James considered The Golden Bowl his best, his most finished work, and the effort to read it is worth it.

__________________________________________________________

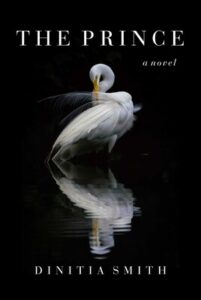

Dinitia Smith’s The Prince is available now via Arcade.