The Secret Language of Tawny Owls

“These are owl woods and always will be unless something is done to remove them.”

Every evening I listen out for the tawnies. On some dark winter days, they call late in the afternoon but usually they wait for dusk and their voice in my mind is inseparable from that subtle and lingering time of day. As the light drops, the stillness of the dark comes on, the trees acquire their night-time solidity, and the hooting of the owls begins. The night mist leaks in as the sun goes down. The dogs’ breath starts smoking in the cold. A jet heads south and in the western sky Venus appears white and washed.

“A tawny owl calls from the wood’s dark hornbeam heart,” J.A. Baker wrote of his Essex woods in The Peregrine.

He gives a vibrant groan; a long sensitive pause is held till almost unbearable; then he looses the strung bubbles of his tremulous hollow song.

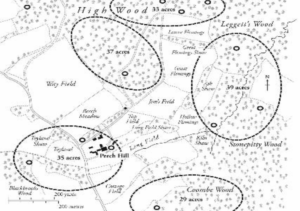

I have spent many early evenings walking in the woods listening to that “hollow voice floating like a sail in the dark,” as Baker described it, trying to map their presence from the calls I can hear around me. It is not easy because the owls are always on the move and I cannot be sure of the boundaries, but the farm is afloat in the owl world, wide pools of owl-life distributed around me in territories of between thirty and fifty acres each.

These are owl woods and always will be unless something is done to remove them. They are as present here as the night air.

Never far from my mind is Olivier Messiaen’s wonderful description of a tawny’s voice: “vocifération douloureuse et lugubre.”

I look at the rough map I have drawn and see in it a country made of owls, as if the owls were as emergent here as the trees. The oak has long been called “the Sussex weed,” as saplings will spring from acorns wherever they are allowed space and time, and the tawny owl is something of the same. These are owl woods and always will be unless something is done to remove them. They are as present here as the night air.

My diary is full of attempts to distinguish one tawny voice from another:

5:58 in the morning and the tawny is still beating on in Stonepitty Wood. The old man of the night, the watchman not yet in bed.

Sometimes the owl in Lower Leggett’s goes a little hesitant. His voice breathes before he means to say anything, like a cry muttered in sleep, a sigh-cry.

The dropping, distant tawny on the far side of Coombe Wood. Sounding as if it is saying ‘Coombe Wood’. Half a mile away, too faint for Merlin.

So mournful the distant owl in Black Brooks. Northern, frosted.

In the half dark of High Wood, the owl hoots around my path. Calling three times, a hoot, a pause, then the shortest and quietest of interruptions, like a comma, very faint, and finally the long wavering, dropping pennant of song, trembling as it ends, with all the owl’s commanding solemnity in it.

No one has ever described these duets between owl and dusk more richly than J.A. Baker in The Hill of Summer. In his account of an Essex owl evening, all senses seem to merge, and all distinction between animate and inanimate disappears. As the dark fills his wood, owl and dark become each other’s intimates.

It was the stillness of the trees that made them so vividly alive. They were drawing together across the last remaining light, closing in, massing. The soft greyness of the wood was hardening to a unity of black . . . A smoke of sounds drifted from the distant village: the fraying bark of a dog, a dusk of voices.

The tawny owl’s dark release of song quavered from the pine wood. The sleek dusk bristled with it, like the fur of a cat. I moved under the gloomy trees. The owl surfed out across the rising night. He could hear the turn of a dry leaf, the relaxing of a twig, the loud scamper of a soft-skinned mouse. To him the silence was a flare of sound, a brilliant day of noises dazzling through the veins of dusk.

Baker’s synaesthesiac grasp of the tawny’s song, in which its voice can ruffle the fur of night and in which silence is luminous, may be reflected in the neural structure of the owl’s brain. As Jennifer Ackerman has described, the Dutch ecologist Kas Koenraads has found that “part of the hearing nerve that goes to the brain, ‘branches off to the owl’s optical centre . . . Owls may actually have a visual image of what they hear. It could be that if an owl hears something moving in the dark and forested environment, it gets some kind of visual information of where the audio cues are coming from.’”

Koenraads could not be sure of this—how can one enter the mind of an owl and see what he hears?—but speculated that when an owl hears something at night, he may see “an illuminated dot of light in the dark forest.”

It is as though the owl is inspecting its own internal oscilloscope screen. But if owls can see what they hear, the distinction between seeing and hearing may not in the end be significant. If we hear an owl, perhaps we are, in a sense the owl would understand, seeing it. Presence is aural in the dark. We see its voice; its body is its voice, so much that to see a tawny owl is uncanny. I remember coming down to the birdhouse one summer night (it was June 3) and seeing one sitting like a finial on the very peak of the building as I approached. As much as the wren coming to adopt the birdhouse as its own, this was another blurring of the boundaries. The tawny slipped silently away as soon as I saw him, off down towards the ash shaw, where after a while he hooted to me in the wood and with my wooden owl call I hooted back.

I have long treasured Edward Thomas’s desolate, wartime poem written in 1915 before he joined up, on the summons made to a wider consciousness by the sadness of the tawny’s voice. Thomas, not yet in the war but struggling with the thought that he should go to France, had been out all day and come into the warmth and comfort of an inn. Inside, with the door shut, he sat by the fire and

All of the night was quite barred out except

An owl’s cry, a most melancholy cry

Shaken out long and clear upon the hill,

No merry note, nor cause of merriment,

But one telling me plain what I escaped

And others could not, that night, as in I went.

And salted was my food, and my repose,

Salted and sobered, too, by the bird’s voice

Speaking for all who lay under the stars,

Soldiers and poor, unable to rejoice.

We all hear that distance and removal in what the owl says, its nakedness and reproach, a song in silence, but Thomas was also responding to something he knew well, the song with which Shakespeare had ended Love’s Labour’s Lost, tracing the story of love and desire through the year, and coming in the end to the winter when

nightly sings the staring owl,

“Tu-whit, tu-whoo!”— a merry note . . .

To Thomas and us this sounds like the oddest of characterizations. We know the owl’s call is far from merry; and most of us know that no owl ever said “Tu-whit, tu-whoo.” The whit and the whoo are from different owls. On a few nights here I have heard an upside-down version of the phrase “Uh-hoo, ke-wick.” It came from two owls, in all probability a male calling as he set off to hunt in the evening and his mate’s response “Uh-hoo, ke-wick” is a double tawny owl statement of close pairing.

True to his reputation as a naturalist, Shakespeare had transcribed a duet of love and partnership between two owls as part of a song of lust and merriment. His instinct was right: always to my own surprise, on the corner of Long Field Shaw, or buried in the depths of High Wood, on autumn evenings or in early summer, nothing sounds merrier than two long-paired, territory-sharing tawny owls greeting each other with “Tu-whoo, Tu-whit.”

I have been on this farm for thirty years. It is likely that one or more of the tawny owls I hear around me has been here almost as long.

We all have tawny owls in our lives. It is the commonest of all owls, perhaps twenty thousand pairs in Britain and a million in Europe. There is a famous pair in Kensington Gardens and they, like many others, hoot in the daytime. They can live for twenty years or so in the wild (the current record is one in Scotland found newly dead twenty-three years after it was first ringed) and they remain attached to their particular pieces of ground. That aged Scottish owl was found two miles from where it had been ringed nearly a quarter of a century before. They never migrate, their young only rarely travel far, and their familiarity with their own country becomes richer year by year.

All this pushes them into a different category from the robins and brings into question Vinciane Despret’s distinction between territory as object and territory as performance. I have been on this farm for thirty years. It is likely that one or more of the tawny owls I hear around me has been here almost as long. The owl’s territory is owned by it for all its adulthood. The same is largely true of Perch Hill and me. How then is our ownership of where we live any different from the birds’?

We recognize at our saner moments that we do not own what we claim to own. I can name more than fifty human occupants of this place over the past centuries. Most if not quite all of those names are of men and each would have been surrounded by at least five or six others. In the 1841 census, fourteen people were living in the farmhouse, nine of them children, three servants. For hundreds of human beings this has been their territory. Our gardens and farms, our houses, porches, lean-tos, gazebos and birdhouses are statements of power and possession but also more than that. Are they not a performance and expression of who and what we are?

Plant a line of roses up to the front door, or fill the flowerbeds around it with aromatic herbs, improve the grazing, build a shed, pasture the cattle and you are engaging with land and space not merely as an owned thing but as a kind of show, a demonstration of a certain kind of life and even belief. A birdhouse dedicated to permeability with the natural world around it is a statement of an ideal. Place may be its medium but it is framed in a way to make explicit a certain kind of attitude to the world.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Bird School: A Beginner in the Wood by Adam Nicolson. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, September 2025. Copyright © 2025 by Adam Nicolson. All rights reserved.

Adam Nicolson

Adam Nicolson is a prize-winning writer of many books on history and nature, including Sea Room, the New York Times bestseller God's Secretaries, and the acclaimed Why Homer Matters. His most recent novel is The Seabird's Cry. He is winner of the Royal Society of Literature's Ondaatje Prize, the Somerset Maugham Award, the W. H. Heinemann Award, and the British Topography prize. He has written and presented many television series and lives on a farm in Sussex.