The secret history of your favorite bad writing cliché: “it was a dark and stormy night.”

“It was a dark and stormy night.” You’ve heard it a million times, seen it used in seriousness and in jest; it is the quintessential and cliché opening to a gothic novel or a ghost story, or as Zachary Petit once put it in Writer’s Digest, “the literary poster child for bad story starters.” But where, exactly, does it come from?

Common internet wisdom points to the opening line of Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s 1830 novel Paul Clifford, which is now otherwise rarely read. The full line goes like this:

It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents—except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.

Holy adjectives, Edward. But in fact, Bulwer-Lytton didn’t invent the phrase—he only made it what it is today: a textbook example of melodramatic, overwritten prose. (And you can see why.) According to English professor Scott Rice (more on him below), “the line had been around for donkey’s years before Lytton decided to have fun with it.” It was at the very least used by Washington Irving in his 1809 satirical book A History of New York, though not as an opening line: “It was a dark and stormy night when the good Antony arrived at the creek (sagely denominated Haerlem river) which separates the island of Manna-hata from the mainland.” Whether Irving was actually the first person to string those seven words together, we don’t know, but we can only assume that it was somehow in the literary ether in the first half of the 19th century.

Since then, of course, it has been used for both good and for ill. It is the way that Madeleine L’Engle opens A Wrinkle in Time (it’s even on the back of the book as a teaser—though apparently early UK editions revised it to “It was a dark and stormy night in a small village in the United States,” which is much less catchy), and the way Ray Bradbury begins Let’s All Kill Constance, though not without an attendant wink:

It was a dark and stormy night.

Is that one way to catch your reader?

Well, then, it was a stormy night with dark rain pouring in drenches on Venice, California, the sky shattered by lightning at midnight.”

Edgar Allan Poe uses it in his 1832 short story “The Bargain Lost,” like this:

It was a dark and stormy night. The rain fell in cataracts; and drowsy citizens started, from dreams of the deluge, to gaze upon the boisterous sea, which foamed and bellowed for admittance into the proud towers and marble palaces.

Neil Gaiman lampshades it in Good Omens:

It wasn’t a dark and stormy night.

It should have been, but there’s the weather for you. For every mad scientist who’s had a convenient thunderstorm just on the night his Great Work is complete and lying on the slab, there have been dozens who’ve sat around aimlessly under the peaceful stars while Igor clocks up the overtime.

The internet has it that the phrase opens “some translations” of Andre Dumas’ 1844 swashbuckler The Three Musketeers, but I could only find a version toward the end, at the beginning of Chapter 65 (Trial). The original French is “C’était une nuit orageuse et sombre, de gros nuages couraient au ciel, voilant la clarté des étoiles; la lune ne devait se lever qu’à minuit.” My translation reads “It was a stormy and dark night; vast clouds covered the heavens, concealing the stars; the moon would not rise much before midnight.”

The point is, it’s everywhere, played both straight and—more often, these days—not so straight. In 1982, an English professor at San Jose State University named Scott Rice founded the Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest, in which entrants are challenged “to write an atrocious opening sentence to the worst novel never written.”

The 2021 winner, written by Stu Duval of Auckland, New Zealand, was chosen from about 4,500 entries. It goes like this: “A lecherous sunrise flaunted itself over a flatulent sea, ripping the obsidian bodice of night asunder with its rapacious fingers of gold, thus exposing her dusky bosom to the dawn’s ogling stare.” (But don’t miss the winners in the other categories, which include Vile Puns, Odious Outliers, and Western.)

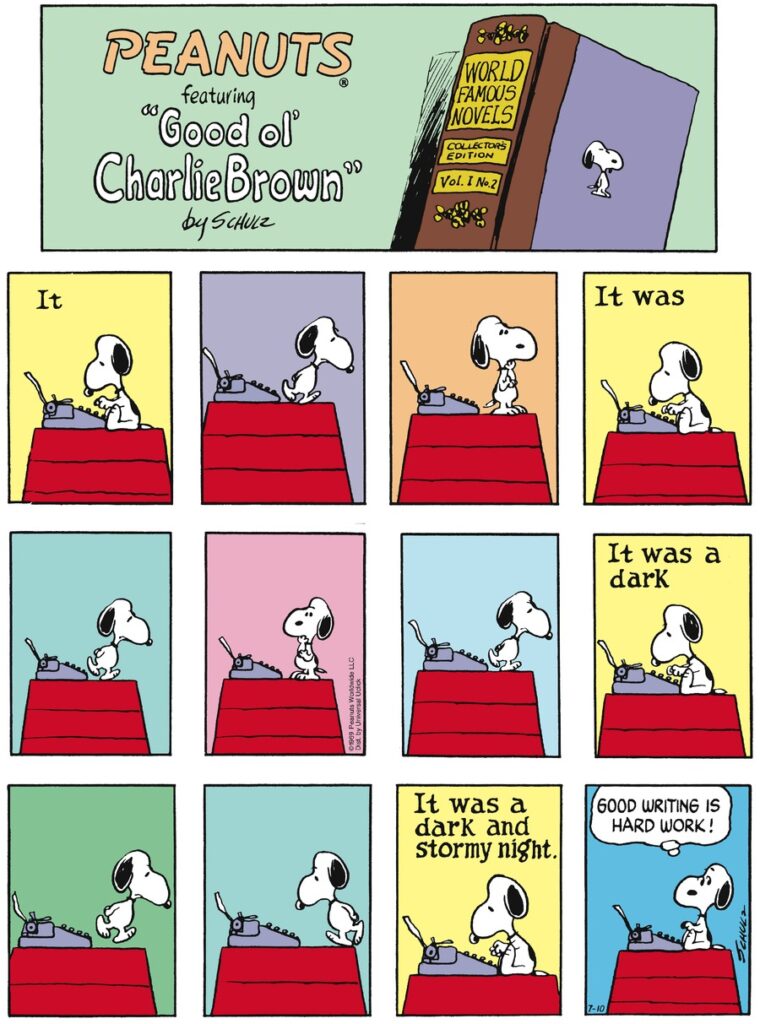

Perhaps most famously, “It was a dark and stormy night” is the first sentence of every novel that World-Famous Author Snoopy tries to write in Charles Schultz’s Peanuts. It first popped up in July 1965, and became such a popular running gag, with so many permutations, that he turned it into its own book in 1971, and the strips have been separately collected into a mini-anthology as well.

Here’s the text of Snoopy’s magnum opus, for the record:

Part I

It was a dark and stormy night. Suddenly, a shot rang out! A door slammed. The maid screamed.

Suddenly, a pirate ship appeared on the horizon! While millions of people were starving, the king lived in luxury. Meanwhile, on a small farm in Kansas, a boy was growing up.

Part II

A light snow was falling, and the little girl with the tattered shawl had not sold a violet all day.

At that very moment, a young intern at City Hospital was making an important discovery. The mysterious patient in Room 213 had finally awakened. She moaned softly. Could it be that she was the sister of the boy in Kansas who loved the girl with the tattered shawl who was the daughter of the maid who had escaped from the pirates?

And so the ranch was saved.

THE END

You have to admit, it’s got everything. Just don’t ask what happened to the king.

According to Susan Campbell, writing for the Chicago Tribune, Rice contacted Schultz to ask him about his use of the phrase, and Schultz explained “that he didn’t know the phrase he appropriated for Snoopy’s thwarted attempts at literature was specific to any one author; he used it only because it was a standard pot-boiler opener that was always out there.”

In 2008, Bulwer-Lytton’s great-great-great grandson Henry Lytton Cobbold stepped up to defend his ancestor’s honor against Rice. “Bulwer-Lytton was a remarkable man and it’s rather unfair that Professor Rice decided to name the competition after him for entirely the wrong reasons,” he told The Guardian. “He was a great champion of the arts, and made such a huge difference to people in all walks of life . . . he was politician, writer, playwright and philosopher.” And as for the line itself? “To have been the first person to have penned a cliché was a mark of genius,” said Lytton Cobbold.

Rice was not impressed.”The ironic thing is: If Bulwer had a phobia, it was being made fun of,” Rice told Campbell. “He thought he was an ‘artiste,’ capital A. Artistes have special privileges. They don’t have to follow the rules like the rest of us.” Oh well.