The Salvific Power of Writing Through Terrible Grief

Maryanne O'Hara on Finding Truth in the Wake of Her Daughter's Death

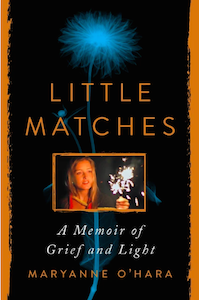

A finished copy of my memoir about my daughter’s death has just arrived in the mail. The book’s gold lettering gleams, catching the sun as I turn it in my hands. I had asked the publisher to please make the cover glow and reflect light, the way my daughter did.

It does, and once again, a piece of writing that I labored over has become a finished entity, a creation of words that can live without me. I am enthralled with it, and bemused. How is it that the author of this soul-baring record, who spent so many hours folded over her keyboard, sobbing, was the same person who started her writing career wanting only to publish short fiction, perhaps a novel? Who told herself she had no interest in writing the personal?

What is the personal, anyway?

At my first writing workshop years ago, the leader, hearing of my two-year-old’s diagnosis with cystic fibrosis, the genetic lung disease, placed an urgent hand on my wrist. “You should be writing your pain!” he said.

I’m sure I flinched. I had no interest in writing pain. Fiction was a way to escape into my imagination, to ruminate on issues that preoccupied me. Inside an invented situation with made-up people, I could forget, for a little while, Caitlin’s health and how it could tick-tock from well to crisis-mode in a matter of days.

CF is a mostly invisible illness. Although her lung function steadily declined as she grew up, on the outside, she lived what many would call a normal life. She was social and bright, with a passion for art history, travel, and philosophy. She discovered Virginia Woolf at a precociously early age, and after reading the Time Passes section of To the Lighthouse, she better understood her mother’s lifelong obsession with “the mystery of our existence within time,” an obsession that was a primary theme in my writing.

Time passing. The passing of time. Waiting for transplant. Waiting inside time. Running out of it.

She existed. And then she did not. And everything fell away and I was left with the fact of me still existing, inside a world that had to make sense if I were to continue living in it.

Writing was the only thing that helped. But it wasn’t fiction I turned to. I had questions and I wanted answers. Where is my daughter? Is there more to life than this life? Does consciousness survive death? Does my existence serve any real purpose? Does anyone’s?

Writing the personal suddenly felt like the only kind of writing that mattered.

I found the process both easier and harder than writing fiction. Easier because I knew the pieces of the story. It was just a matter of artfully putting them together, or so I imagined. With no wonder or curiosity about where my imagination might take me, I expected that it would be more of a slog to create that first draft. But it was no more of a slog than any first draft. So much of it was no different from writing fiction. You bring your people to life. You choose which details to include, how to shape the particular story you are trying to tell. Happily, the joy and magic of writing—of discovery—happened as I wrote the memoir, just as it always had with fiction.

The hardest part of writing the personal was, well, that it was so personal. I began the process only nine months after her death. People asked me why I was doing that to myself, but it felt important to write from inside real-time grief, to make a record of it. And there was another reason, too. I feared that my memory of her would—not fade—but morph into a version of Caitlin who had never quite existed. Who she was, in real life, was splendid enough. I wanted to write that person, share her writings, immortalize her in a small way—she who had not been able to author her legacy.

I could only function in small doses, so I took to setting a timer and writing a set number of minutes each day. Every Monday, I sent my pages to a writer friend who promised to expect those pages and keep me honest.

After the book was well into production, I woke up one morning and thought, what have I done? I’ve bared my soul. There is no fiction label to shield me. But . . . it was done. It is done. It is here at last, on my desk.

We writers often finish a piece and look on it with admiration that is almost outside of ourselves, wondering, how did I do that? How did I write those words that flow and connect? How did I knit those layers into that tight, narrative weave that reveals nothing of the labor that went into the process? I page through this book that has miraculously managed to come to life and try to grasp that I did it. Was the process as effortless as its beauty makes it appear?

Of course not. I pick up my phone and search for a video I’d taken early in the book’s creation. It’s a little trick of mine, one I’ve developed over the years, and it’s not just for writing. When times are hard or when a task is difficult, I make notes or recordings to myself, to have later, so I can counteract the amnesia that inevitably sets in when a thing is done. The concrete reminders serve as motivation when a project or activity seems too difficult to proceed with.

I find the video from January 25, 2018. On that day, I had completed 25 coherent first pages and hung them side by side on my upstairs hallway walls. This is another trick, one I learned in graduate school from Pamela Painter, a wonderful teacher. Spreading out a story’s component parts can help you to see the whole. You can physically walk among the words and live inside them, see how they flow or don’t flow, how they might be re-arranged. The rest of the notes for the book consisted of neat piles of pages, many of them, organized by date, theme, and subject.

I play the 40-second video and listen to myself. “Okay,” I had said, as I panned across the rows of hanging pages. “If you ever manage to finish this book and make it into something good, I want you to remember how impossible it seemed on this day when you had hung it all up and then put it into piles and tried to make a coherent story.” I had moved the camera into the guest room, where the piles covered the bed and the floor, and then I’d climbed upstairs to where more piles lined another bed, another floor. “I mean, there are pages everywhere; there are just piles and piles and piles and piles.” Big sigh. Then a doubtful, “I don’t know…”

What kept me going? The questions I was asking. The revelation I was looking for. My daughter. The people who encouraged me. And the literature I love.

“What is the meaning of life?” Virginia Woolf wrote. “That was all—a simple question; one that tended to close in on one with years. The great revelation had never come. The great revelation perhaps never did come. Instead, there were little daily miracles, illuminations, matches struck unexpectedly in the dark; here was one.”

Every writer I know has two selves—one who records what is happening as the other experiences what it knows it will one day write about. Even in the worst hours of grieving my daughter’s death, a part of me knew I would be striking matches and discovering what the light revealed.

I’ve always proclaimed that fiction can tell universal truths better than a lot of nonfiction. And I believe that to be true. But there’s room for all of it, isn’t there? I couldn’t have and wouldn’t have wanted to fictionalize our story. The bare-bones truth of it is its power.

__________________________________________________

Maryanne O’Hara’s Little Matches: A Memoir of Grief and Light is available now via Harper.