The Roiling Mess: Mairead Small Staid on Italo Calvino, Anne Carson, and Love Stories

“Want spins like a pendant at the end of a chain, now a noun, now a verb.”

Perhaps this matters, in considering my happiness: I’m in love. The kind that begins in an instant, quick as a wink—in this case, he actually winks. The kind that begins as a crush and continues: I’m crushed and crushed again. Such insistence has a thrill to it, a pleasure: I’ve always loved having my blood pressure taken, the tightening cuff. We won’t sleep together in Italy, won’t so much as kiss in three months rife with wine and cobbled streets and the sweet Mediterranean beyond, below, around.

He has a girlfriend back home, and I am too fearful to test that limit—I would like to say too good, but no, it’s fear—and these facts keep us circling like prizefighters, sizing up the damage we might do.

But isn’t that the moment the crowd roars for, the moment each loves most of all? Before the match begins, when anything might happen? Forget what I said before: who knows what won’t occur? I write in the present tense.

*

Outside the Museo Leonardiano in Vinci towers a sculptural rendering of the Vitruvian man, the man—or men, two men, with arms and legs outstretched at different angles—pressed together like paper dolls and enclosed in the many ribs of a rotated circle. Our art history professor, a thin, brilliant man near seventy with a sky-wide American accent, summarizes Vitruvius’s belief: the geometry of the human figure proved that man was the most beautiful being in creation.

“Vitruvius wasn’t that intelligent,” the professor drawls, and my friend Annie laughs. Annie convinced me to beg my way into this seminar on Leonardo—I’m the only student in the class not studying art history back home. I don’t know what quattrocento posture entails or who Giotto is. When the others select one of the famous paintings for their presentation topic, I take the allegories and the rough sketches for impossible flying machines. I’ll come to love the artist’s notebooks more than the Mona Lisa—but who wouldn’t?

The flying machines are the focus of Leonardo’s hometown museum—the paintings, too pricey for this village attraction, are at the Uffizi or the Louvre or the National Gallery in London. We gaze instead at massive wooden wings suspended over our heads, the sketches of a Renaissance genius given modern, if immobile, life. This is more than they ever got in Leonardo’s time, the professor explains: manifold as the artist’s interests were, paper was as far as most of his ideas went. With the weary affection accrued by a lifetime spent studying the man, the professor rolls his eyes at the wings and the accompanying sketches. “Very clever,” he says. “And very impractical.”

I’ll come to love the artist’s notebooks more than the Mona Lisa—but who wouldn’t?

Leaving Vinci, we bus to a foundry in Pietrasanta, where limbs of bronze and plaster fill the buckets at our feet, awaiting bodies. A foundry worker peels back a mold to reveal the statue within, a woman made of dark bronze by the artist Maria Gamundi. Annie nudges me, nodding to the pinups cooing on the far wall. The workers plunge another mold into a massive tub of water, steam pouring into the air and reddening the faces behind their beards. I’m not sure which—the statue or the pinups, the uniform metal or the photographed flesh—is more perfected, more Ideal than real, though I can guess.

Then we travel up, up the coast and into the mountains, so we can shiver in the marble caves of Carrara, where Michelangelo’s David came from, and his Pietà. We don hard hats and listen to a guide detail how arduous the work: to get at the stone within the stone, to transport so many tons of rock without damage. In the cavernous dark, the marble looks gray and seamed with dirt— who knew or trusted enough to haul such heavy blocks out of the mountain and into the dazzling light? Another touching faith was practiced in this flame-lit, freezing darkness, as breath plumed and vanished from the quarriers’ mouths.

The morning’s fog has lifted, and the mountainside blazes as we drive away, continuing northward: Annie has asked the professor to drop us at the train station in La Spezia before the rest of the seminar goes back to Florence. We’re headed elsewhere.

Before and between Marco Polo’s descriptions of the cities he has seen—cities of labyrinthine traps or shifting skylines, cities abandoned to the winds or filled with faces vaguely known, cities within cities within cities—Calvino offers his own descriptions, of the conversations between Polo and the emperor Kublai Khan.

“Newly arrived,” Calvino writes, “and totally ignorant of the Levantine languages, Marco Polo could express himself only with gestures, leaps, cries of wonder and of horror, animal barkings or hootings, or with objects he took from his knapsacks … the ingenious foreigner improvised pantomimes that the sovereign had to interpret.” In the preceding chapters, then, and in the ones to come, are we reading Polo’s account of each city or Khan’s interpretation of each wordless pantomime? How many translations stand before us, of language and experience and gesture and gut?

In another novel by Calvino, Cosmicomics, a character describes a thing she has built as “an outside with an inside in it.” Reading Leonardo’s notebooks, I encounter: “A good painter has two chief objects to paint, man and the intention of his soul; the former is easy, the latter hard.” Or, in other words: This is what we try to do, yes? Make what we show on stage who we really are? We bare our souls, or their intentions, or whatever it is we hope will be mistaken for our souls and their intentions—or we hide them entirely, because we are fearful or calculating or simply unable, unable to translate the roiling mess inside us into something another can understand.

How many translations stand before us, of language and experience and gesture and gut?

The day was cloudy in Vinci and Pietrasanta, but Riomaggiore glitters in the sun. Beyond the railroad tracks, between the houses, the Tyrrhenian Sea lashes the rocky shore. Annie and I climb the town’s stone-paved road to find the hostel office. The woman behind the desk is the first person we’ve met, after three weeks in the country, whose English is worse than our Italian, so we get to practice. We are ecstatic.

She leads us out of the office and farther up the street, our legs straining against the precipitous angle. The town, as in a fairy tale, has been carved out of the cliff’s side. Our room—and we don’t see anyone else in the building, so it feels like our house, our home—is as high, we can’t help feeling, as one can go. A balcony looks out over the cobbled street, the teetering buildings, and the crashing, happy ocean below.

Our friend Vignesh and his roommate are meeting us here. Annie and I go to school with Vig, back in the States, though none of us knew each other well there—here, we feel as close as family. Vig is good-natured, down to travel and ready with laughter, and accepts our constant, sisterly teasing with aplomb. We tease him about his bulky, pickpocket-thwarting money pouch; about how slowly he walks, a laidback Californian trailing two Northerners; about how a well-meaning study-abroad counselor told him—Vig is barely taller than Annie or I, and far gentler—that he’d have to protect us girls, in Italy. Our protector! is Annie’s regular greeting for him, and his regular response: Yes, yes, don’t worry, I’m here.

They arrive on the evening train from Florence; Vig tows a rolling suitcase for the weekend trip, which we tease him about. Annie and I have been in Riomaggiore for hours now, have eaten focaccia with fresh pesto and drunk a bottle of wine, so we show Vig and his roommate to the hostel with proprietary pride: here is our balcony, our cliff side, here is the shop where we buy focaccia and wine. There is our hostel owner, with whom we speak Italian. There is our rocky coast, our very own Tyrrhenian. We eat pizza by the side of the carless street and the evening light—it’s mid-September—lingers longer than seems possible, given the restrictions of our planet and its atmosphere.

“The Greek word eros denotes ‘want,’ ‘lack,’ ‘desire for that which is missing,’” writes Anne Carson in Eros the Bittersweet. “The lover wants what he does not have. It is by definition impossible for him to have what he wants if, as soon as it is had, it is no longer wanting.” Our own language puts it as plainly, welding two meanings together to form the word: want spins like a pendant at the end of a chain, now a noun, now a verb. “This is more than wordplay,” Carson insists. “There is a dilemma within eros.”

In the early novels of ancient Greece, this dilemma underpins the narrative form: two lovers wish to wed or are wed and have been separated; something or some hundred things keep them from each other; in the final pages, after much struggle, they succeed at last in union or reunion. The author, Carson tells us, must provide and vary—artfully or not—the many impediments necessary to sustain the story, frustrating the lovers’ desires just long enough to fill a book.

Though it collapses, inevitably, in the final pages, “a sustained experience of paradox” is what these tales provide; Carson likens the lovers’ journey to those imagined by Zeno. Desiring to be together, destined to be together, they spend most of the story apart. “It is the enterprise of eros to keep them so,” says Carson. “The unknown must remain unknown or the novel ends.”

We are fearful or calculating or simply unable, unable to translate the roiling mess inside us into something another can understand.

The week before, back in Florence, we’d left the dark bar charmed—by the singer, by the songs, by the pathos of the empty tables and the pride we took in filling them—and walked back up the street, through the piazza, past the gardens and museums, unseen, unknown. The others split off, one after the next, turning onto streets that led to their own temporary homes, until I walked alone with our musician friend, Vig’s roommate—let’s call him Z.— whose host family lived across the railroad tracks behind my own apartment, so that for him to walk me home was not out of his way, not really, maybe by a block or two, at most.

When we reached my apartment, we sat to smoke; he pulled a pouch of tobacco and papers from his jacket pocket, and I retrieved a carton from mine—he hadn’t yet shown me how to roll my own. We smoked, and talked, our knees jutting toward each other in the limited space allowed by the building’s stoop. Such a small and common thing, my knees, but I grew keenly aware of them, tucked into their jeans; and of my hands, the welcome interlude of cigarette between their fingers; and of my eyes, counting as if by their will and not my own the seconds spent meeting his, the seconds spent looking away.

_______________________________

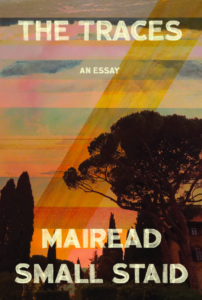

The Traces by Mairead Small Staid is available from Deep Vellum

Mairead Small Staid

Mairead Small Staid is a MacDowell Fellow and a graduate of the Helen Zell Writers’ Program at the University of Michigan, where she received Hopwood Awards in nonfiction and poetry. Recent work can be found in AGNI, The Believer, The Georgia Review, Kenyon Review, Narrative, Ninth Letter, and Ploughshares.