The Rise of Carlos the Jackal, the Most Feared Terrorist of the 1970s

Jason Burke on the Early Years of an Infamous Icon of Political Violence

The twenty-four-year-old gripping the Beretta 9mm pistol in his gloved hand had enjoyed many names in his short life. To teasing classmates, he had been el Gordo or “the chubby one.” To fashionable friends in London’s nightclubs, he was Illy. To his girlfriends in France, he was Johnny. In the Middle East, he was Saleem Mohammed. To the customs officials who checked his documents at various international airports, he was usually José Adolfo Muller Bernal, a Chilean academic.

To British authorities, meanwhile, he was Carlos Martínez Torres, a Peruvian businessman whose passport photograph—clearly in need of updating—showed a nineteen-year-old with a round face, full lips, a prominent nose, sharp chin and eyes obscured by large oval sunglasses.

José, Johnny, Saleem, Adolfo or Carlos had spent the penultimate day of 1973 preparing to shoot dead Joseph Edward Sieff, the Jewish president of Marks & Spencer, a major retail chain whose upmarket shops were to be found on high streets across Britain, and a prominent supporter of Israel. To this end, the young man had travelled to a mock-Georgian mansion on a quiet, elegant street in north London, not far from Regent’s Park.

It was a cold evening and the street was unusually dark. In response to Syria and Egypt’s surprise attack on Israel that October, aided by massive military support from the USSR, in which tens of thousands of infantry and hundreds of tanks had invaded simultaneously across the Suez Canal in the south and the Golan Heights in the north, the US had leapt to Israel’s defense, allowing its forces eventually to repulse the attack after a series of desperate engagements resulting in heavy casualties.

In the immediate aftermath of the short war, to protest at US support for Israel, Arab producers did what they had threatened to do for several months and deployed the “oil weapon,” announcing a series of price hikes and production cuts. Coming at the same time as industrial action by British coal miners and railway workers, the consequent energy crisis had led the Chancellor of the Exchequer to announce the country’s “gravest situation since the end of the [Second World] War.” Police were told to replace vehicle patrols with bobbies on foot, a speed limit of fifty mph was imposed, and the nation’s three TV channels were ordered to stop broadcasting at 10.30 PM. On Queen’s Grove, where the young man now stood, the streetlights were dimmed, as they had been across much of London, to save electricity.

The career of “Carlos the Jackal,” which stretched from the final moments of 1973 to the mid-1980s, did not reveal the strength and success of the international revolutionary “armed struggle” so much as its incipient decline.

At around 7 PM, as Sieff was preparing for dinner, his doorbell rang. His butler opened the door and, seeing the Beretta in the young man’s gloved hand, led the visitor to the bathroom where Sieff was dressing. The intruder pushed the door half open, raised the weapon and squeezed the trigger. There was a single deafening report. The weapon then jammed and the attacker fled, running down the stairs, out onto the street, and disappearing into the dark.

To his significant surprise, Sieff survived. Metal dental work in his upper jaw deflected the bullet, and within a month he was convalescing on an extended holiday in Bermuda.

The real name of the man who had tried to kill him, the name written on his birth certificate, issued in the Venezuelan capital Caracas twenty-four years previously, was Ilich Ramírez Sánchez. But it was as Carlos, the name on his favored passport, that he would become infamous. It was not until excitable tabloid journalists found a copy of Frederick Forsyth’s bestselling novel The Day of the Jackal in his former girlfriend’s apartment that he acquired the second part of his memorable sobriquet. The fact that the book was not his did not bother the headline writers. Ramírez would be known as “Carlos the Jackal” for the rest of his life.

Before the attack that night in north London, Ramírez had never before fired a round in anger, let alone attempted to shoot someone dead at close range. Within six years, he would be credited with scores of killings perpetrated on almost every continent, as well as almost supernatural powers of infiltration and evasion, a fanatical devotion to revolutionary ideology, and a principal role in orchestrating a network of terrorist operatives who were supposedly some of the Cold War’s most effective fighters and influential actors. The many myths and inaccuracies that surrounded him not only disguised the bloody, chaotic and cynical reality of Ramírez’s activities, but greatly assisted them. This indeed was the theatre of terrorism suggested by Brian Jenkins of the Rand Corporation.

The reality was that the career of “Carlos the Jackal,” which stretched from the final moments of 1973 to the mid-1980s, did not reveal the strength and success of the international revolutionary “armed struggle” so much as its incipient decline. For Ramírez, as for many others involved in international extremist violence at the time, the middle years of the 1970s undoubtedly brought opportunities to further their cause and violent careers. Yet, like those who had launched the international armed struggle over the previous decade, they attained very few of their more ambitious objectives, and only a handful of their less inspiring ones. Many failed to reach the relatively modest goal of staying alive.

*

Newspapers in Britain carried the story of the attack on Sieff on their front pages. Detectives told reporters they were hunting a man who was around five feet eleven inches tall with a foreign accent and dark complexion, wearing a green parka-type anorak with a fur-trimmed hood. The police had overestimated Ramírez’s height by an inch or two but most of the other details were correct. Detectives checked hotels and boarding houses in London, asking landlords and -ladies if the suspect had been a guest, and interrogated taxi drivers. Their enquiries bore little fruit, not least because the object of their search lived with his mother and two younger brothers in a two-bed flat in the west of the city and had driven to the scene of the attempted assassination in the family estate car

Two months later, Ramírez attempted another attack, this time on an Israeli bank in the City of London. Again, his efforts were only partly successful. He failed to throw the shoebox containing his bomb cleanly through the establishment’s doors, and so caused only superficial damage to the building and slight injury to a cashier. Once more, police made desultory enquiries and soon lost interest, their investigative resources stretched thin by a recent string of bombings in London by Irish republican extremists. It would be more than two and a half years, after the deaths of five people, including two French policemen, and a series of near misses that could have killed hundreds, before British security services finally identified the perpetrator of the attack.

At the time he tried to kill Sieff, Ramírez had been in Britain for seven years. His childhood was unusual but considerably less eventful than either he or his detractors later claimed. Though he had been given the surnames of both his parents—Ramírez and Sánchez—as was customary in Venezuela, his first name had been chosen by his father, a successful lawyer with strong left-wing views for whom Lenin was a hero. The Russian revolutionary’s real name had been Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov, so Ramírez, the second of three brothers, got Ilich. The family were wealthy, and Ramírez enjoyed a comfortable if somewhat unstable upbringing. There were sufficient funds to hire private tutors and for a lengthy tour of Central America and the Caribbean during a period of extreme political instability in Venezuela at the end of the 1950s. While in Jamaica, the Ramírez boys were sent to a very conservative private school to learn English and were punished for refusing to sing the British national anthem in morning assembly.

Back in Caracas, the family rented an apartment in the slightly rundown neighborhood of El Silencio. Ramírez attended the Liceo Fermín Toro, a public school with a reputation for revolutionary politics and catering to high-society families of slightly bohemian inclinations. Timid and overweight, he was neither very interested in the former nor popular among the confident, stylish offspring of the latter, though like many pupils he did join the local Communist party’s youth branch. Party officials and friends who knew him at the time do not remember the teenager doing anything to suggest the violent direction his life would soon take.

When his parents’ rocky marriage broke down definitively, Ramírez left Venezuela with his mother and brother for London. He did not particularly impress the teachers at the small, expensive and undemanding school where he was enrolled. “He is not yet as clever as he thinks or imagines. He talks far too loudly and too long,” wrote one. Slimmer and more self-assured now, dressed in suits and a tie, always charming and polite, Ramírez made more of an impression when accompanying his mother to diplomatic functions on the Latin American cocktail circuit.

Two years later, his son having attained A levels in English, maths and sciences, Ramírez’s father flew to Europe to arrange for his further education. One possibility was the Sorbonne in Paris but soaring property prices and recent political unrest made the French capital unattractive. Instead, strings were pulled in the Venezuelan Communist Party and Ilich and his brother were found places at the Patrice Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University in Moscow. Here the two brothers found themselves among around 3,000 overseas students from eighty or more countries. Their new home had been set up “as part of [the USSR’s] drive to lessen the traditional ties of newly emerging states with the Free World,” the CIA explained in a secret intelligence assessment in 1968, which was only part of the story. The institution was named after the first democratically elected prime minister of the Republic of Congo, who had been ousted and assassinated in 1961 by its Belgian former colonial rulers and their proxies to forestall any possibility that he might swing the newly-independent state into the Soviet camp.

The university was one of an array in the USSR and eastern Europe that offered free education to thousands of students from the developing world. Most courses lasted four to six years, with compulsory Russian language instruction for the first two, and a significant amount of Marxist dialectics throughout. Not only was tuition free, students also received a generous stipend and an allowance to buy warm clothing. The spacious lecture halls and hostels of the Friendship University were significantly superior to its overcrowded counterparts in western Europe at the time, but discipline was strict and students were strongly discouraged from traveling even around Moscow.

Ramírez, who was supposed to be studying chemistry and physics, ignored such strictures. Funded by a sizeable allowance from his father, he ate frequently in local restaurants, drank in bars and repeatedly brought women back to his room, many of them sex workers. Nor did his habit of challenging teachers during lectures win him many friends among the academic staff. When university authorities nonetheless suggested to the Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti, the USSR’s main intelligence service, that Ramírez might be a candidate for recruitment, the KGB demurred, deciding that “his appalling record as a student” and dissipated lifestyle made him entirely unsuitable as an agent.

The immediate cause of Ramírez’s expulsion from the university in July 1970 was not his ostentatious womanizing, poor grades or contrarian attitude, but the sudden decision of the fractious Venezuelan Communist Party to withdraw its vital sponsorship of dozens of students at the end of his second year. This was not a rare occurrence at the university, where the presence of many students depended on the outcome of factional battles in their countries of origin. Ramírez was not overly vexed by the premature end of his studies in the USSR, but instead of returning to Britain he flew to Beirut where he set about finding the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine.

Ramírez had no particular interest in the Middle East, still less the Palestinians, but it was a long-held ambition of his to train as a guerrilla fighter. His father had spoken to him of the exploits of relatives who had fought for radical causes in Latin America, and he had spent his adolescence hearing about men like Castro and Guevara. His immediate aim was to learn the military skills that would allow him to join a breakaway Communist faction in Venezuela that had launched an armed insurgency there. A small number of Nicaraguans at Lumumba University, all members of the Sandinistas, held similar hopes of being trained by the Palestinian fedayeen in order to better fight at home. They may have inspired Ramírez or simply instructed him on how best to fulfill his ambition.

Before departing Moscow, the young Venezuelan had obtained a letter of introduction to the PFLP from Arab fellow students who were involved with the group. With this in hand, he now set out along the well-worn path to the offices of the al-Hadaf newsletter in Beirut. On arrival, like so many others before him, he was directed to Bassam Abu Sharif. At first skeptical of the young, smartly-dressed visitor, Abu Sharif soon found himself impressed by his knowledge of current affairs and charmed by the beautifully engineered camera he had brought from Moscow as a gift. The young Venezuelan was dispatched to spend the afternoon in the Shatila refugee camp on what was then the southern outskirts of the city before being dropped at a nearby hotel, as was routine. Usually, the foreign visitors would wait days before the Popular Front got back in touch. This time, however, Abu Sharif decided to take this latest new arrival to dinner at a local Italian restaurant to continue their earlier, enjoyable conversation.

He had his heart set on activism of a more disruptive nature. Eventually, more than two years after his return from the Middle East, the call came.

At this point, three years before the Israeli special forces raid into the heart of Beirut put an end to such things, life in the city was much easier for the fedayeen. Soon other members of the Popular Front joined the pair and the increasingly lively group went on to a nightclub. After hours of dancing and drinking, Ramírez was dropped off back at his lodgings. A night or so later, he bumped into Gunnar Ekberg, the Swedish spy, at a small restaurant. The two had seen each other earlier in the day at the al-Hadaf office, where Ekberg was waiting to meet Wadie Haddad. Recognizing each other, they shared a convivial bottle of Chateau Musar. Shortly afterwards, Ramírez was in a taxi on his way to one of the training camps in Jordan where international volunteers were still being hosted.

Ramírez arrived in Amman at the moment when the fedayeen groups were at the height of their power and belligerence, and the kingdom was teetering on the brink of all-out conflict. Fatah were hosting Andreas Baader and his comrades at one camp; other foreign volunteers were at the camps where Leila Khaled had trained in the hills further north. Due to the growing tension, Ramírez was among a contingent of newly arrived volunteers who were hosted in cheap hotels in the back alleys of the Jordanian capital rather than being dispatched to the more distant training facilities where foreigners usually stayed.

The trainees nonetheless followed much of the usual syllabus, being ferried daily to one or other of the big Palestinian refugee camps under PFLP control for lectures and drills in unarmed combat and very basic weapons handling. Unused to the diet, heat and poor hygiene, Ramírez fell ill, though neither diarrhea nor stomach cramps prevented him from complaining vociferously about his accommodation, arguing with his instructors about tactics and questioning his hosts’ more grandiose claims of military prowess.

In early September, with the multiple hijackings organized by Haddad and a final confrontation with King Hussein’s forces both looming, the Popular Front leaders in Amman decided that the foreign volunteers were a liability and arranged for them to be bussed back to Lebanon out of harm’s way. This may have been completed before the bitter fighting of the autumn, or it may have occurred after a delay of days or even weeks. Ramírez may have helped guard a Popular Front base in the north of Jordan during the first round of fighting, as some accounts suggest, and he may have been close to targets hit by Israeli jets, as is often reported, but it is unlikely he participated, as he occasionally later claimed, in actual combat.

Once back in Beirut, Ramírez quickly made himself at home. He found the American University a more congenial environment than the battered shacks and open sewers of the Palestinian refugee camp where he was supposed to be staying, and spent much of his time on its campus. Eventually, after more than three months of debate, lectures, occasional physical drills and wine-fueled evenings, he flew from Beirut to Amsterdam where he pretended to have lost his passport with its tell-tale stamps from Jordan and Lebanon. Once he had obtained clean documents from the Venezuelan consulate there, he travelled on to London in late January of 1971, where he moved into the spare bedroom of the apartment that his mother and brother were now renting in a 1930s mansion block on Kensington High Street. A month later, he was reprimanded by a family friend for not telling his parents where he had been through the autumn and winter. “I’ve been in the Middle East, learning how to kill Jews,” Ramírez replied.

One of the first things Ramírez did on returning from Lebanon was to sign up for a course of lectures in economics at the University of London. He also taught Spanish two afternoons a week at a secretarial college near Hyde Park where he tried without success to seduce his students, took some Russian lessons to maintain the moderate proficiency he had acquired in Moscow and continued to accompany his mother to soirées organized by the Latin American community. At a Christopher Columbus Day celebration, he met Nydia Tobón, a tall, intelligent leftwing lawyer fifteen years his senior who had come to London from Colombia after separating from her husband. The two became lovers. They talked a lot about politics—the Middle East, the struggle for revolution around the world, the breaking Watergate scandal in the US—in pubs on the Fulham Road or cafés in Soho and went to the Royal Festival Hall to listen to Tchaikovsky.

London offered various activities for a person interested in revolutionary ideology or political and social transformation. Time Out magazine listed “demos and meetings” alongside “prog rock” gigs, “health food” restaurants and experimental “fringe” theatre. Every weekend protesters somewhere in the city shouted, marched and occasionally clashed with police, whether to highlight the injustices faced by distant populations battling “imperialist-backed” regimes or those fighting discrimination in Britain itself. Ramírez, who boasted that Napoleon brandy was his favorite drink and enjoyed Cuban cigars with a game of poker, ignored all of this, preferring to spend his free evenings at The Playboy and Churchill’s, two expensive West End members’ clubs known for their “hostesses” and occasional patronage by minor celebrities.

Beyond his obvious fondness for the life of a well-heeled young expat in the still slightly swinging British capital, there was another reason for Ramírez to avoid the haunts of London’s radical left: he had his heart set on activism of a more disruptive nature. Eventually, more than two years after his return from the Middle East, the call came.

__________________________________

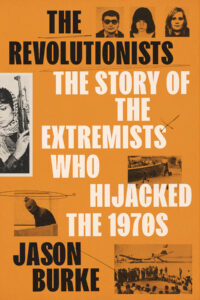

From The Revolutionists: The Story of the Extremists Who Hijacked the 1970s by Jason Burke. Copyright © 2025 by Jason Burke. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Jason Burke

Jason Burke, the International Security correspondent for The Guardian, has been a foreign correspondent for almost 30 years, reporting from the Middle East, South Asia, Europe and Africa. He is one of the foremost writers on Islamic militancy and the author of four critically acclaimed books: The New Threat: The Past, Present, and Future of Islamic Militancy, The 9/11 Wars, Al-Qaeda: The True Story of Radical Islam, and On the Road to Kandahar: Travels through Conflict in the Islamic World. He lives near London.