The Rise of Arthur Ashe: Tennis Star, Civil Rights Activist

"I finally stopped trying to be part of white society."

Arthur Ashe’s double victory in the U.S. Amateur and the U.S. Open changed his life beyond recognition. During the fall of 1968, the 25-year-old Army lieutenant discovered what it was like to be a true celebrity. As a top-flight tennis player and the only African American on the men’s tour, he was accustomed to a certain amount of attention. But he had no previous experience with the intense media scrutiny and public exposure that accompanied national acclaim. Suddenly, his off-court activities and opinions were a matter of public interest as privacy gave way to influence and visibility. “Being thrust on center stage,” he later recalled, “gave me a great opportunity to reach people.”

Ashe’s new life of interviews, cover stories, and public appearances began in earnest a week after the Open when he appeared on Face the Nation hosted by Martin Agronsky. Face the Nation featured interviews with prominent politicians and newsmakers, and Ashe was the first athlete to be interviewed on the show since its debut in 1954. Poised and articulate, he handled Agronsky’s questions with surprising ease for someone so young. In rapid succession, he held forth on a number of issues related to race, civil rights, and the civic responsibilities of black athletes.

He returned to these themes later in the week as a guest on The Joey Bishop Show, a late night talk show on ABC, and he also appeared on The Dating Game, trumpeting his status as an eligible bachelor. In early October, he joined several other black celebrities as a guest on Soul, a new Ford Foundation–funded variety show aimed at New York City’s black community. Sitting onstage with the likes of Malcolm X’s widow, Betty Shabazz, he could hardly believe his good fortune. Life as a celebrity was becoming fun.

Ashe’s accomplishments soon made the pages of magazines ranging from The New Yorker to Vogue, and in late September he even found himself on the cover of Life. The cover photo captured a steely-eyed Ashe charging the net, and inside the magazine a flattering, five-page photo essay concluded with a brief but revealing interview by David Wolf. “Detachment—that air of icy elegance—is part of Ashe’s image now,” Wolf insisted. “It is an extra piece of identification that will enhance his celebrity. Paul Hornung had his harem. Ty Cobb his uncontrollable rage. Arthur Ashe has his cool.”

“In rapid succession, Ashe held forth on a number of issues related to race, civil rights, and the civic responsibilities of black athletes.”

Arthur himself seemed to agree, declaring: “What I like best about myself is my demeanor. I seldom get ruffled.” But when asked to explain his recent success on the tour, he steered the conversation in an entirely different direction. In the past, he told Wolf, he had lacked a secure sense of racial identity and a realistic connection to the world around him. Sheltered and protected by his father, he had been “preconditioned to think in a segregated environment.” “There were places we couldn’t go, but we just accepted it,” he explained. “Now I realize that has a deep effect. You grow up thinking you’re inferior, and you’re never quite sure of yourself.”

His newfound confidence and assertiveness on the court, he reasoned, had a lot to do with his recent decisions to assert himself off the court. During the last two years, following his graduation from UCLA, he had been inspired by “a social revolution among people my age. I finally stopped trying to be part of white society and started to establish a black identity for myself.” That evolving identity had led him to support the Olympic boycott movement, to become involved in the Urban League’s inner-city programs, and to try to make up for years of inattention to social and racial issues. “I’m not the favorite person of a lot of people in the black community,” he confessed. “I’ll be the first to admit that I arrived late. I’ve got a backlog of unpaid dues.”

In November, Arthur’s newfound activism found further public expression in a lengthy profile in Ebony magazine. Although “in the early days black militancy was not his bag,” feature writer Louie Robinson Jr. reported, “a different Arthur Ashe speaks today . . . his attitude on his responsibilities in the cause of black justice has changed. . . . Ashe sees himself as ‘definitely more militant’ today, and believes his old idea of simply achieving as much as one can individually and ‘setting an example’ is not enough.” “It’s changed mostly because I’m older and wiser,” Arthur insisted, adding, “Then there’s outside pressures. What was liberal five years ago may be moderate now.” In keeping with the spirit of the times, he had moved beyond the guiding principles of his carefully controlled Richmond boyhood, summarized by Robinson as “be neat and clean, work hard, mind your manners and don’t cause trouble.” While Arthur still adhered to the first three principles, he no longer put much stock in the fourth. As a freethinking adult, he was determined to do what he could to advance the cause of social justice, even at the risk of being labeled a troublemaker.

Arthur did not, however, go looking for trouble, at least not yet. If he felt sure of himself when addressing an issue, he did not hesitate to speak his mind. Yet on a number of issues related to race and politics he was still mulling over his options. A case in point was his mixed response to the Olympic boycott controversy. The proposed boycott by African nations had become moot in April when the IOC sustained South Africa’s banishment from the Olympics. But the continuing agitation by Harry Edwards and the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) placed considerable pressure on African American athletes either to stay away from the Summer Olympics in Mexico City or to make some sort of gesture on behalf of black solidarity once they were there.

On October 16th, two black American Olympians, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, shocked Olympic officials and much of the sporting world by doing just that. After placing first and third in the 200-meter dash, the two San Jose State runners, both OPHR members, appeared at the medal ceremony wearing black socks but no shoes. When the American national anthem began to play, each man bowed his head and raised an arm with a black-gloved hand held high, a gesture widely interpreted as a Black Power salute. Suspended from the American delegation, Smith and Carlos immediately became symbols of racial pride to some and objects of derision and outrage to others. Ashe couldn’t decide quite how to react to their provocative violation of the Olympic ban on political protest. Years later he would praise Smith’s and Carlos’s courage, but at the time he made no public statement on the matter. What Edwards called “the Revolt of the Black Athlete” had begun, but Ashe wasn’t sure he was ready to join the revolution.

“If he felt sure of himself when addressing an issue, he did not hesitate to speak his mind. Yet on a number of issues related to race and politics he was still mulling over his options.”

At this point in his life, he was having too much fun to be an ideologue. The Life and Ebony profiles both noted his jet-setter lifestyle and the fun-loving side of his character, especially when it came to women. According to Wolf, Arthur’s Davis Cup teammates envied “his collection of beautiful girls of all colors,” and Robinson pointed out that in Arthur’s “part of the tennis world, the food is good . . . the accommodations are comfortable, and the girls are plentiful. And while Arthur’s sense of restraint prevents his qualifying as a playboy . . . the pleasures are considerable.” To make the point, Robinson ended the piece with the image of Arthur being picked up at the Los Angeles airport by a chauffeured Cadillac limousine, compliments of the comedian Bill Cosby. “Arthur eased himself inside,” Robinson wrote admiringly, “and glided off into the velvety blue of the California night. He never lost his cool.”

Arthur could hardly be blamed for enjoying the moment and taking a measure of pride in his new status. He was, after all, a black man born and raised under the dominion of Jim Crow—the first of his race since Althea Gibson to become a Grand Slam champion and bona fide tennis celebrity. He had reached the mountaintop, and the climb up had not been easy. He had also arrived at the pinnacle of American tennis under less than ideal conditions as a wartime Army lieutenant on leave. Somehow, the tumultuous months of 1968—a time rent with political protests and assassinations and deep social divisions—had proven to be his breakthrough year.

Arthur’s achievements during this time—his last full year as an amateur—were nothing short of remarkable. Playing in only 22 tournaments, he won 10, including both the U.S. Open and the U.S. Amateur. His overall match record of 72–10 represented a winning percentage of 87.8, one of the highest figures in the history of competitive tennis. A semifinalist at Wimbledon, he made the finals of the U.S. Open doubles and led the American Davis Cup team to victory, winning 11 of 12 singles matches. When the final American rankings for the year were released, no one was surprised that Arthur was ranked number one.

Public acknowledgment of his stature came in many forms, from magazine cover stories to laudatory comments by his peers. But one sure sign of his new status during the fall of 1968 was the hovering presence of the journalist John McPhee. A leading practitioner of an emerging genre known as creative nonfiction, McPhee had gained considerable fame as an essayist for Time and The New Yorker, producing a series of memorable biographical profiles, including several on Princeton basketball star Bill Bradley. Published collectively in 1965 as A Sense of Where You Are, the Bradley pieces demonstrated McPhee’s interest in the cerebral side of athletic competition. Raised as the son of the Princeton athletic program’s staff physician, he was fascinated by the higher-order mind-body connection displayed by Bradley and other true student athletes.

Tired of writing individual profiles, he had begun to toy with the idea of writing a dual profile, and in early September 1968 the televised U.S. Open semifinal match between Ashe and Graebner presented him with just what he had been looking for—two talented and complex individuals worthy of joint study. His goal was to produce a detailed narrative that would reveal hidden truths about a seemingly transparent subject—in this case, competitive tennis. Anticipating the “thick description” technique perfected by the noted anthropologist Clifford Geertz in the 1970s, McPhee undertook a comprehensive study of the text and context of the Ashe-Graebner match.

“Arthur could hardly be blamed for enjoying the moment and taking a measure of pride in his new status. He was, after all, a black man born and raised under the dominion of Jim Crow—the first of his race since Althea Gibson to become a Grand Slam champion and bona fide tennis celebrity. He had reached the mountaintop, and the climb up had not been easy.”

The result was a series of New Yorker essays that ultimately became Levels of the Game, a sports book like no other. After securing Ashe and Graebner’s cooperation, McPhee acquired the kinescope of the match from CBS. He also obtained a large but portable Bell and Howell projector that allowed him and his protagonists to watch the match frame by frame. Throughout the fall of 1968, he dragged the projector from site to site, wherever Ashe or Graebner, or in some cases their family members, happened to be. From West Point and the Graebners’ New York apartment on East 56th Street to Gum Spring and San Juan, the questions and observations never flagged.

McPhee wanted his readers to feel the rhythm and logic of the match, but he also wanted to present richly textured biographical portraits that ranged across space and time. There was the match, with its physical architecture of serves and volleys, and there was human behavior, personal and quirky, decisions of the moment rooted in years of parental guidance and coaching, repetitive practice, and real-life experiences both good and bad. There were also cultural and political contrasts—an avowedly liberal black man from Richmond, a disinherited son of the South, ranged against the privileged son of a conservative Cleveland dentist, a proud representative of the white Republican establishment.

Life magazine’s Donald Jackson described Levels of the Game as “probably the best tennis book ever written,” and Robert Lipsyte of The New York Times speculated that McPhee might have reached “the high point of American sports journalism.” Many readers found the taut narrative to be reminiscent of Ernest Hemingway’s prose—sparse but gripping. Some were undoubtedly hooked before finishing the first paragraph, which describes the physics of Ashe’s serve:

Arthur Ashe, his feet apart, his knees slightly bent, lifts a tennis ball into the air. The toss is high and forward. If the ball were allowed to drop, it would, in Ashe’s words, “make a parabola and drop to the grass three feet in front of the baseline.” He has practiced tossing a tennis ball just so thousands of times. But he is going to hit this one. His feet draw together. His body straightens and tilts far beyond the point of balance. He is falling. The force of gravity and a muscular momentum from legs to arm compound as he whips his racquet up and over the ball.

With this opening description of mechanical artistry, McPhee set the stage for a searching exploration of the physical and psychological aspects of competitive tennis. Ashe was fortunate to be one of the two individuals caught in McPhee’s penetrating gaze, which magnified his emerging stardom, ensuring he would never again live as an ordinary private citizen.

__________________________________

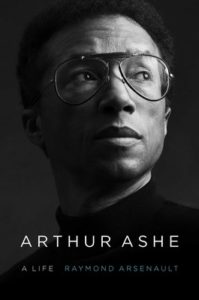

From Arthur Ashe: A Life. Courtesy of Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2018 Raymond Arsenault.

Raymond Arsenault

Raymond Arsenault is the John Hope Franklin Professor of Southern History at the University of South Florida, St. Petersburg. One of the nation’s leading civil rights historians, he is the author of several acclaimed and prize-winning books, including Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice and The Sound of Freedom: Marian Anderson, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Concert That Awakened America. His latest book, Arthur Ashe: A Life, is available from Simon and Schuster.