The Rest Principle: On the Necessity of Recovery, in Fitness and Writing

Bill Hayes Applies the Lessons of Personal Training to the Life of a Writer

On a rainy, cold morning in late October 2011, twenty-five suspiciously fit young men and women—and me—gathered in an otherwise empty New York gym to become certified personal fitness trainers.

I did not plan to train people professionally but hoped to learn what one must learn to become a trainer, and to build on my layman’s knowledge of exercise, anatomy, and kinesiology. Others were definitely there to start a new career. They were dancers, actors, ex-jocks (male and female alike), and waitresses and bartenders who no longer wanted to wait tables and tend bar. Over the next eight weeks, we would attend classes from nine am to five pm every Saturday and Sunday—over 120 hours of study.

Our instructor introduced himself and began his lecture. What we first saw on-screen was not all that different from what one would have seen illustrated some four hundred years earlier in Vesalius’s Fabrica: a literal muscle man, a body stripped of skin to show the topmost layer of muscles beneath. Memorizing the main muscles of the human body and, more to the point, understanding their role, location, and function would be a foundation of our learning. As important as knowing what muscles help us do—lift, jump, squat, lunge, flex—would be fully appreciating what they prevent us from doing: falling apart, folding in on oneself, crashing to the floor. The lumbar spine provides the only skeletal support between the rib cage and the hips, for instance, so most other support for this area comes from the muscles that make up the abdominal wall. Running three layers deep in front and on each side, the abs help contain major organs of the digestive system—like the top of a Tupperware container sealed tight—and help one stand upright.

Muscles get the lion’s share of credit and attention when it comes to exercise, but the reality is that movement—exercise at its essence—actually occurs at joints. These come in six types: ball-and-socket, hinge, condyloid, pivot, gliding, and saddle joints. The movements they make can be defined by the plane in space along, or within, which they take place: the frontal plane (side to side movements), sagittal (flexion and extension), and transverse (twisting and rotating). These planes are not seen, obviously—they have to be envisioned—but once one is aware of them, one sees the body, movement, and working out differently. Ideally, a workout is based on different planes of movement, not merely on different body parts. So, on a “chest day,” you wouldn’t want to perform only exercises in the transverse plane— presses, push-ups, and so on. Instead, you want to mix in exercises that involve other planes of movement, other directions, creating a dynamism that will help shape your body more symmetrically and will, incidentally, be kinder to your joints.

*

The eight-week course in personal training went by in a blur. Since I was working full-time at a day job, my nights were filled with studying biomechanics, basic physiology, kinesiology, and more. Indeed, this was a time in my life when I more often took flash cards than lovers to bed. And when I did take lovers, I dissected them with my eyes and quizzed them: Is this your femur or your tibia? May I please palpate your gluteus medius? I always pointed out the beauty of the inguinal canals, the twin lines right below the waist where the lower abdominals meet the pubic area.

My career didn’t depend on my passing the final exam, but my self-respect did. The oldest guy in the class couldn’t be the only one who failed. Fortunately, I passed with a respectable score and received my certification. All these years later, I still recall the six principles on which a long-term personal fitness training program can be built—a major part of our final exam. Not because I have a stellar memory, but because, in each of these concepts I found a correlative to my work, my passion—to writing—although they could apply equally well to just about any vocation or endeavor.

First, there is the Principle of Specificity. This states that what you train for is what you get: If it is strength you want, train for strength. In short, be specific in your work goals as much as in your workouts. It’s all in the details.

Next, the Overload Principle: train a part of the body above the level to which it is accustomed. You must provide constant stimuli, so the body never gets used to a given task; otherwise, expect no change. Push yourself, in other words, try new things, whether at the gym, at your desk, or in the office—creative cross-training, one might say.

In some cases, it’s not just the writing that needs a breather but the writer, too.This leads to the Principle of Progression. Once you master new tasks, move on. Don’t get stuck—whether on a given task or an exercise regimen. If you do, this will lead to the Principle of Accommodation. With no new demands placed on it, the body accommodates or reaches homeostasis—not a good place to find oneself. So don’t get too comfortable; it will show in your work as clearly as in the mirror.

When stimuli are removed, gains are reversed—use it or lose it, as the Principle of Reversibility emphasizes. Just as movement in any form is better than none at all—walk around the block if you can’t make it to spin class—one must do something, anything, to keep the creative and intellectual motors running.

And finally, the Rest Principle, the tenet that gave me particular solace. To make fitness gains, whether in strength, speed, stamina, or whatever your aim (see Principle of Specificity), you must take ample time to recover.

I had been working out as long as I had been writing, so this last principle was not new to me. But I had never observed this rule very strictly when it came to working on a piece of writing. Just as the body needs time to rest, so does an essay, story, chapter, poem, or especially, a book.

In some cases, it’s not just the writing that needs a breather but the writer, too. After completing my book The Anatomist, I wrote virtually nothing for almost three years. I hadn’t given up writing deliberately, and I cannot pinpoint a particular day when my not-writing period started, any more than one can say the moment when one is overtaken by sleep. It’s only after you wake that you realize how long you were out.

Nor did I feel “blocked” at first. Lines would come to me and then slip away, like a dog that loses interest in how you are petting it and seeks another hand. This goes both ways. When I lost interest in them, the lines gradually stopped coming.

I didn’t miss writing, yet I felt something missing—a phantom voice, one might say. I had been pursuing writing since I was a teenager, had published pieces in many places, and had written three books back-to-back. To have silence and neither deadlines nor expectations for the first time in years was sort of nice—and sort of troubling. Can one call oneself a writer when not-writing is what one actually does, day after day?

I never lied. If someone asked, I would say that I wasn’t working on anything and no, had nothing on the back burner, in the oven, cooking, percolating, or marinating. (What’s with all the food metaphors anyway?) I wasn’t hungry either. But I was tired. Very tired. And thinking about the “Rest Principle” helped me find my way back to writing and provided validation for what I had done instinctively. On this matter, I quote from the National Council on Strength and Fitness training manual, one of the textbooks we used in our course: “As the rate of motor unit fatigue increases, the effect becomes more pronounced, causing performance to decline proportionately to the level of fatigue… During the recovery period, the muscle fibers can rebuild their energy reserves, fix any damage resulting from the production of force, and fully return to normal pre-exertion levels.”

Translation: Don’t work through the pain; it will only hurt. Give yourself sufficient time to refresh.

How long should this period be? What is true for muscle fibers is true for creative ones as well. My rule of thumb in fitness training is two-to-one: for every two days of intense workouts, a day off. However, “in cases of sustained high-level output,” according to my manual, full recovery may take longer. This is what had happened with me creatively. I needed a really, really long rest.

Then one day a line came to me. It didn’t slip away this time but stayed put. I followed it, like a path. It led to another, then another.

Soon, pieces started lining up in my head, like cabs idling curbside, ready to go where I wanted to take them. But it wasn’t so much that pages started getting written that made me realize my not-writing period had come to an end. Instead, my perspective had shifted. Writing is not measured in page counts, any more than a writer is defined by publication credits. To succeed at any endeavor, whatever it may be, is to make a commitment to the long haul, as one does to keeping fit and healthy for as long as possible. For me, this meant staying active both physically and creatively, switching it up, remaining curious and interested in learning new skills—I took up photography—and of course giving myself ample periods of rest. I knew that the writer in me, like the fitness devotee, would be better off.

_______________________________________________________________

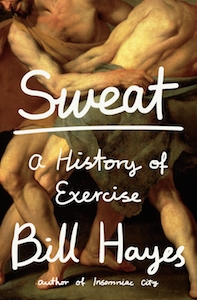

Excerpted from Sweat: A History of Exercise by Bill Hayes. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury Publishing. Copyright © 2022 by Bill Hayes.