The Resilience of Nature Gives Jane Goodall Hope

The Legendary Naturalist Talks to Douglas Abrams About Growth, Regeneration, and Survival

Jane Goodall was in the middle of telling me her reasons for hope.

“Let’s take a walk,” Jane said the next morning. We pulled on our jackets and went outside, the air chilly as the north wind greeted us, blowing through the trees of the preserve. “We can make something hot when we get back,” Jane encouraged as we pulled the door closed. “It’s good to have at least one walk a day,” said Jane, after a few steps. “Though I don’t really like to go for a walk without a dog.”

“Why is that?”

“A dog gives a walk a purpose.”

“How?”

“Well, you are making someone else happy.” I thought of the rescue dogs at Jane’s house in Tanzania, and how she never seemed happier than when she was surrounded by all creatures great and small.

It was a beautiful walk around a small lake, and Jane served as field guide, pointing out the sights she had seen the day before. The trees were mostly leafless, the land in winter slumber.

After we had walked for about thirty minutes, the sun broke through the clouds, illuminating a large tree in the distance.

“Let’s go as far as that tree in the sun,” Jane said, “and then turn back.”

I was happy to move toward any spot of warmth. The tree was tilted to the side after many years of being buffeted by the strong winds.

When we arrived, Jane rested her hand on the moss-covered trunk of a magnificent Turner’s oak.

“Here’s the tree I wanted to come and say hello to. . . . ‘Hello, tree.’” The tree sheltered us from the wind as the sun fell across our faces.

“It’s beautiful,” I said, touching the spongy green moss that Jane was stroking affectionately. Jane had told me that as a child she had a deep bond with a beech tree in her garden. She used to climb up and read her Doctor Doolittle and Tarzan books, disappearing for hours into the tree’s leafy embrace and feeling closer to the birds and the sky.

“Did you have a name for that tree?”

“Just Beech,” Jane said. “I loved him so much that I convinced my grandmother—we called her Danny—to give him to me for my fourteenth birthday and even drew up a last will and testament for her to sign, gifting me Beech. I used a basket and a long piece of string to haul up my books and sometimes even did my homework up there. And I dreamed of going to live with animals in wild places.”

“I know you’ve mostly studied animals, but you also learned a lot about plants when you were researching your last book, Seeds of Hope.”

“Yes, and I absolutely loved that experience—what a fascinating world, the plant kingdom. And when you think about it, without flora there would be no fauna, would there! There would be no humans. All animal life ultimately depends on plants if you think about it. It’s a kind of amazing tapestry of life, where each little stitch is held in place by those around it. And we still have so much to learn— we’re like babes in the wood when it comes to really understanding nature. We haven’t even begun to learn about the myriad of forms of life in the soil beneath us. Just think—the roots of this tree are way down there, knowing so much that we don’t—and taking the secrets up to the branches above us.”

As Jane looked from the ground up toward the very top of the tree, I had a vivid picture of her up in Beech, being rocked by the wind. I also thought of how her hands had rippled in flight in Tanzania as she was describing the murmuration of starlings and how she had said a naturalist needed to have empathy, intuition, even love. I wanted to know what she had found in the deepest mysteries of the natural world, and why what she discovered there gave her a sense of peace and hope for the future that I desperately wanted to find.

“Jane, you say the resilience of nature gives you hope—why?”

Jane smiled as she looked at the large tree in front of us. Her hand was still resting on its mossy, gnarled, and ancient bark.

“I think that I can answer your question best with a story.”

I’d noticed that Jane often answered questions with stories, and I mentioned that to her.

“Yes, I’ve found that stories reach the heart better than any facts or figures. People remember the message in a well-told story even if they don’t remember all the details. Anyway, I want to answer your question with a story that began on that terrible day in 2001—9/11—and the collapse of the Twin Towers. I was in New York on that day when our world changed forever. I still can remember the disbelief, the fear, the confusion as the city went quiet save for the wailing of the sirens on the police cars and ambulances on the streets emptied of people.”

“We still have so much to learn— we’re like babes in the wood when it comes to really understanding nature. We haven’t even begun to learn about the myriad of forms of life in the soil beneath us.”

My memory flashed back to that brutal day as those two pillars of our modern world came crashing down. Having grown up in New York, I felt the attacks in a deep and personal way, as everyone knew friends or family who were in the towers or nearby when the attack occurred. I thought of the enormous crater at Ground Zero, the destruction, the horror of it all.

Jane continued her story. “It was ten years after that terrible day that I was introduced to The Survivor Tree, a Callery pear tree, who had been discovered by a cleanup worker a month after the collapse of the towers, crushed between two blocks of cement. All that was left was half a trunk that had been charred black with roots that were broken; and there was only one living branch.

“She was almost sent to the dump, but the young woman who found her, Rebecca Clough, begged that the tree might be given a chance. And so she went to be cared for in a nursery in the Bronx. Bringing that seriously damaged tree back to health was not an easy task, and it was touch-and-go for a while. But eventually she made it. And once she was strong enough, she was returned to be planted in what is now the 9/11 Memorial & Museum. In the spring her branches are bright with blossoms. People know her story now. I’ve seen them looking at her and wiping away tears. She truly is a symbol of the resilience of nature—and a reminder of all that was lost on that terrible day twenty years ago.”

Jane and I stood quietly, thinking about the resilience of that tree. And then Jane began to speak.

“There’s another story about a survivor tree which is even more dramatic in a way,” Jane said. “In 1990 I visited Nagasaki, the city where the second atomic bomb was dropped at the end of World War Two. My hosts showed me photos of the absolute and horrifying devastation of the city. The fireball produced by the nuclear explosion reached temperatures equivalent to the sun— millions of degrees. It was like a lunar landscape or what I imagine Dante’s Inferno might look like. Scientists predicted that nothing would grow for decades. But, amazingly, two five-hundred-year-old camphor trees had survived. Only the lower half of their trunks remained, and from that most of the branches had been torn off. Not a single leaf remained on the mutilated trees. But they were alive.

“I was taken to see one of the survivors. It’s now a large tree but its thick trunk has cracks and fissures, and you can see it’s all black inside. But every spring that tree puts out new leaves. Many Japanese regard it as a holy monument to peace and survival; and prayers, written in tiny kanji characters on parchment, had been hung from the branches in memory of all those who died. I stood there, humbled by the devastation we humans can cause and the unbelievable resilience of nature.”

Jane’s voice was full of awe and I could tell she was far away, remembering that encounter.

I was moved by those two stories. But still I was not sure how the stories of these irrepressible trees could serve as one of Jane’s main reasons that there was hope for our world and for our planet.

“But tell me, what does the survival of those trees tell you about the resilience of nature more generally?”

“Well, I remember a really bad bush fire at Gombe that swept through the open woodlands above the forested valleys. Everything was charred and black. Yet within a couple of days after one little shower of rain, the whole area was carpeted with the palest of green as new grass pushed up through the black soil. And a little later, when the rainy season began in earnest, several trees that I had been sure were completely dead started thrusting out new leaves. A hillside resurrected from the dead. And, of course, we see this resilience all around the world. But it’s not just the fl ora; the fauna can regenerate, too. Think about the skinks.”

“Skinks?” I asked.

“It’s a type of lizard that shakes off its tail to distract predators who pounce on the wildly wiggling tail while the skink makes a getaway. Then, right away, the skink starts growing a new tail from the bloody stump. Even the spinal cord grows back. Salamanders grow new tails in the same way, and octopuses and starfish grow new arms. The starfish can even store nutrients in a severed arm, which sustain it while it grows back a new body and mouth!”

“But aren’t we pushing nature to the breaking point? Isn’t there a point at which resilience becomes impossible, a point where the damage suffered is irreparable?” I asked Jane. I was thinking of our emissions of greenhouse gases that trap the heat of the sun and that have caused temperatures around the globe to rise already by 1.5 degrees Celsius. And this, in addition to habitat destruction, is contributing to the horrifying loss of biodiversity. A 2019 study published by the United Nations reports that species are going extinct tens to hundreds of times faster than would be natural and that a million species of animals and plants could become extinct in the next few decades as a result of human activity. We’ve already wiped out 60 percent of all mammals, birds, fish, and reptiles—scientists are calling it the “sixth great extinction.”

I shared these fears with Jane.

“It’s true,” she acknowledged. “There are indeed a lot of situations when nature seems to have been pushed to the breaking point by our destructive behavior.”

“Yet,” I said, “you still say you have hope in nature’s resilience. Honestly, the studies and projections about the future of our planet are so grim. Is it really possible for nature to survive this onslaught of human devastation?”

“Actually, Doug, this is exactly why writing this book is so important. I meet so many people, including those who have worked to protect nature, who have lost all hope. They see places they have loved destroyed, projects they have worked on fail, efforts to save an area of wildlife overturned because governments and businesses put short-term gain, immediate profit, before protecting the environment for future generations. And because of all this there are more and more people of all ages who are feeling anxious and sometimes deeply depressed because of what they know is happening.”

“There’s a term for it,” I said. “Eco-grief.”

______________________________________________________________

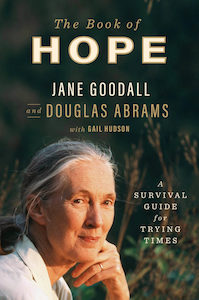

From The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times by Jane Goodall and Douglas Abrams. Copyright (c) 2021 by the authors and reprinted by permission of Celadon Books, a division of Macmillan Publishing Group, LLC.

Jane Goodall and Douglas Abrams

Dr. Jane Goodall DBE is an ethologist and environmentalist. From infancy she was fascinated by animal behavior, and in 1957 at 23 years old, she met the famous paleontologist Dr. Louis Leakey while she was visiting a friend in Kenya. Impressed by her passion for animals, he offered her the chance to be the first person to study chimpanzees, our closest living relatives, in the wild. And so three years later Jane travelled from England to what is now Tanzania and, equipped with only a notebook, binoculars and determination to succeed, ventured into the then unknown world of wild chimpanzees. Jane Goodall’s research at Gombe national park has given us an in-depth understanding of chimpanzee behavior. The research continues, but in 1986, realizing the threat to chimpanzees throughout Africa, Jane travelled to six study sites. She learned first-hand not only about the problems facing chimpanzees, but also about those facing so many Africans living in poverty. She realized that only by helping local communities find ways of making a living without destroying the environment could chimpanzees be saved. Since then Jane has travelled the world raising awareness and learning about the threats we all face today, especially climate change and loss of biodiversity. Author of many books for adults and children and featured in countless documentaries and articles, Jane has reached millions around the world with her lectures, podcasts and writings. She was appointed as a UN Messenger of Peace, is a Dame of the British Empire and has received countless honors from around the world. Douglas Abrams is the New York Times bestselling co-author of The Book of Joy: Lasting Happiness in a Changing World with the Dalai Lama and Desmond Tutu, the first book in the Global Icons Series. Douglas is also the founder and president of Idea Architects, a literary agency and media development company helping visionaries to create a wiser, healthier, and more just world. He lives in Santa Cruz, California.