The Reproductive Movement Must Reclaim Its Radical Roots and Be More Inclusive

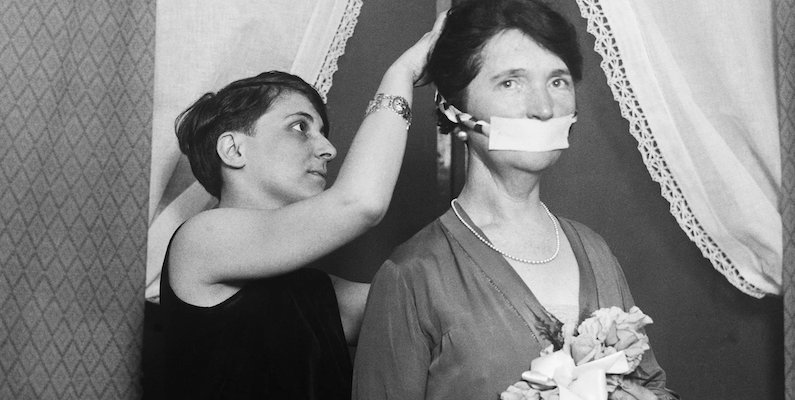

Julie Carr on Margaret Sanger's Difficult Legacy, Comstockery, White Supremacy in Healthcare Today, and More

More than to any of the other women I discovered in my family archive, I am drawn to my great-aunt Iris. Like her, I am the mother of daughters. Like her, I like to read and write. Like her, I grow food (a comparatively tiny amount). Her “ideal church,” she tells her father Omer Kem, would be “a community gathering place where everybody is welcome and a free exchange of ideas is allowed.”

This would be my ideal church too. And Iris was close to her father, as I am close to mine. It was only when I began to read Iris’ letters in earnest that I found myself yearning for these relatives I had never met.

Hers is the voice that most clearly articulates the passions of motherhood and daughterhood, that most poignantly expresses what kinship means, what belonging is. But then, in the 1920s and ’30s, as her writing and thinking matures, Iris is the one family member, besides my great-grandfather Omer himself, who directly reveals the kinds of distortions kinship with and belonging to a white property-owning family in America can foster.

Though in Omer and Iris’ America—the America of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—the distribution of birth control materials and information was criminalized, this hadn’t always been the case. Some women, white married middle- and upper-class women, had always had access to these materials.

But in the mid-nineteenth century, as poor rural people, immigrants, Black people, and many unmarried women flocked to cities, such materials were marketed to them also: “Everywhere one looked…contraceptive information, ads, and other materials were visible.” The industrialization and mass migrations of the postbellum years brought many more married and unmarried women into contact with the commercialization of contraception and the freedom from patriarchal control that it allows.

The inevitable backlash against all these frankly displayed signs of sex was codified in 1873, when “purity” crusader and guilty masturbator Anthony Comstock, though not a legislator, wrote a national “anti-obscenity” bill to criminalize the circulation and sale of such “obscene” information and materials (drugs, gels, diaphragms, condoms).

The industrialization and mass migrations of the postbellum years brought many more married and unmarried women into contact with the commercialization of contraception and the freedom from patriarchal control that it allows.

In 1873 teenaged Omer was digging ditches in the Indiana mud, though his first wife, Nan, was already pregnant with their first baby, a boy named Edwin, who died before turning one. Over the next seven years, Nan would endure four more pregnancies, just about as many as one can have in that amount of time. She was either nursing or pregnant or both right up until her death at twenty-nine. It seems that in those years, “obscene” materials, legal or not, had not been available to a poor rural woman like her.

The year of Comstock’s crackdown, 1873, was a pivotal year for other reasons as well. Just eight years after the war, and following a panic on the banks, the country faced its first Great Depression. The “panic of 1873,” wrote Du Bois, “altered the face of society” by leading to a four-year depression, followed by a consolidation of wealth in the hands of the few and a shift in the labor movement away from interracial class solidarity toward craft-based unionism.

In the northern cities, the streets were flush with the jobless poor, while in the Midwest, miners and factory workers faced wage reduction or sat idle. In the South, meanwhile, Reconstruction was attacked by “Redemption,” with its swelling waves of anti-Black terror. In Colfax, Louisiana, for example, where Black men had briefly made up the majority of the electorate and state assembly, a group of white paramilitary terrorists attacked the Black state militia with guns and cannons, killing (or later executing) up to 150 Black men.

What Comstock’s crackdown on “obscenity” might have had to do with this inflection point in racial capitalism is something I’ve not seen explored, and I can’t explore it here either. But without a doubt, Reconstruction, immigration, and urbanization inspired great fears in white people in the South and North, fears having to do with racial “contamination” and the status of white workers. And racial anxieties, as can be observed in present-day America, seem always to inspire concurrent anxieties about the sexual lives of women.

The dawn of the new century brought a crackdown on free speech from another direction as well. After Leon Czolgosz assassinated President McKinley in 1901, anarchists, socialists, and especially members of the radical wing of the labor movement, the IWW, found themselves frequently thrown in jail for speaking their views in public.

In response, these same groups waged an intensive defense of the First Amendment in the streets—staging protests, filling jail cells, publishing diatribes. The early birth control movement, led by Margaret Sanger, but which included free-speech, free-love anarchists like Emma Goldman, aligned itself with this truly valiant struggle for freedom, a struggle that led to the arrest and torture of hundreds, if not thousands, of people.

In the early twentieth century, the worker-led free-speech movement and the woman-led birth control movement emerged almost as one, responding to and resisting the same oppressive and reactionary forces waging war against their voices, their bodies, and their hopes for more just futures.

And yet, as is now commonly known and often decried, in around 1920, Sanger shifted the movement away from its radical roots. Under her leadership, the movement began to align itself instead with the growing eugenics movement and its anti-immigrant, racist, ablest, and classist ideology.

That year Sanger organized the first American Birth Control Conference in New York to purposely follow directly after the Second International Conference of Eugenics, hosted by eugenicists Fairfield Osborn and Madison Grant, author of the stupendously fascistic The Passing of the Great Race. Alongside her own first voicings of eugenic ideas, Sanger also made space in the Birth Control Review for leading voices in the eugenics movement, some of whom, like Paul Popenoe, Havelock Ellis, and Guy Irving Burch, advanced venomously racist and nativist beliefs and policies.

If I had hoped that the birth control movement’s anarchic origins had been as attractive to my ancestors as they were to me, I would be disappointed. By the time father and daughter were avidly discussing the project of birth control in the 1920s, it was fully “grafted” to the eugenics movement. Indeed, had it still been associated with anarchism or socialism, they would never have embraced it.

*

Iris’s advocacy for birth control can best be found in two speeches she gave to the Olathe Women’s Club in 1924 and 1925, just around the time that Sanger was establishing the country’s first long-term birth control clinic, Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau, in New York City. In the first of these speeches, “Birth Control as I See It,” Iris’s opening sentence is telling: “My purpose in coming before you today to discuss this question is not because I believe you, as individuals, are in particular need of birth control.” Rather, she goes on to explain, birth control is a matter for other women—poor women, immigrant women, urban women—a way of “doing away with misery and crime” through “controlling the birthrate” of the poor.

Iris gathers professional support by naming a series of male doctors, including some from her town, Montrose, Colorado, who support legalizing contraception, “reliable persons” all. Iris’s final point pertains directly to the West, the frontier that once functioned as a “safety valve” for what many called “surplus populations”: “There are no more vast unoccupied territories to send our young men to,” she observes.

By the time father and daughter were avidly discussing the project of birth control in the 1920s, it was fully “grafted” to the eugenics movement.

While once we might have been able to send them off to colonies, like Britain had done, these colonies are also rapidly filling up, as was the rest of the non-Western world: “China is terribly overcrowded, so is Japan, India is even more so.” What’s more, Iris goes on, in these countries, people are not dying of famine and disease like they used to. “These countries are now learning how to take care of their babies and cure their sick. India is saving thousands who died before.” Faced with all this excessive unwanted life, there is only one answer: birth control.

A year later, in another speech to the same body of women, Iris goes beyond this neo-Malthusian argument. “Pioneer Life in Olathe as Seen by the Coreys” is a mostly nostalgic talk in which she traces the early experiences of settler families in Colorado’s Uncompahgre valley. When she was a child, she tells her listeners, she and her siblings would play “Indian”: “Our play was always most realistic because we found so many evidences of former Indian occupation” (here she complicates her earlier depiction of “vast unoccupied territories”).

As an adult, Iris did some research—mostly talking to old-timers—to better understand the pattern of dispossession she and her family took part in: “The whites in Colorado became incensed at the Ute Indians, and being covetous of the fertile lands they occupied, brought about their removal.”

As the speech continues, Iris emphasizes her gender-based empathy with Ute women: “This must have been a sad Journey, as sad as the departure of the Arcadians. This had been their home and they were certainly exiles. Chipeta, Chief Ouray’s wife, must have been near heartbroken at leaving her home.”

And yet despite this sad journey, this heartbreak, Ute removal makes a space that is quickly filled: “The morning after the departure of the Utes, came the rush of settlers to occupy the land,” she acknowledges. These first settlers include Iris’s in-laws, the Coreys, and then, sixteen years later, her family, the Kems. After admitting to this opportunistic land theft, Iris shifts gears to describe some of the difficult challenges the early settlers faced.

For twenty-two paragraphs, she details their clothing, their food production, and their struggles to develop transportation and education. And then, at the very end of her speech, Iris takes a rather abrupt turn, as if she’s just then remembered that she is speaking to women, that she has a message particular to them:

Those women suffered hardships and achieved many things, but we women of today have hard things to do and much to conquer if we would leave the world a better place than when we came into it. We have the vote, which our pioneer mothers didn’t have, and with it we can do much if we will. Assisting at the birth of new babies can safely be left to the doctors of today, but who dare say that it shouldn’t be in the hands of women to say what kind of babies shall be born and when they shall be born. May women soon awake to their opportunities and use them for the betterment of the race.

In his mind-opening book The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America (2018), Greg Grandin argues that the frontier didn’t “close” with the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890 or with white settlement in Oklahoma. Rather, the “expansionist imperative” kept America moving far beyond its physical borders into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

As reproductive justice is so unevenly distributed across race, citizenship, and class, who, really, is being menaced, and by whom?

Ballooning imperialist projects echo and reignite the logic of early America’s wars of western expansion. From the Spanish American War in 1898 to early twentieth-century occupations in Latin America and the Caribbean, from the First World War, the Korean War, and Vietnam to the so-called war on terror—all this functions much the way the western frontier did: uniting (certain) Americans under a shared aggressive ideology.

The “spread of democracy” justifies all these wars, just as the “spread of civilization” justified Indian genocide and the annexation of Mexico. But while aggression is spun as progress, Grandin argues, “the promise of boundlessness” keeps us forever distracted from the racism and inequality that has always given the lie to the mission.

Grandin’s argument is powerful, and everyone should read his book. But there is yet another frontier in America that he doesn’t mention, one that can never close: the white woman’s reproductive body. Iris’s narrative of the pioneer woman’s journey is one of progress, despite the “sad” story of Indian dispossession and genocide that made that progress possible.

Through white women’s struggles, lands have been cultivated, children educated, and democracy expanded. And now, says Iris, there are other lands to “conquer.” No modest proposal, Iris tasks “we women” with the role of curating the human race itself.

White women, she suggests, are uniquely and newly positioned to be the arbiters—through the vote—of the awesome power of reproduction. For Iris’s generation, women are no longer just breeders; they are now also deciders. And as white women decide “what kind of babies shall be born and when they shall be born,” we make the world, the whole wide world, “better.”

Toward the end of her earlier speech, Irish unleashes the truly supremacist nature of her passion. “If we can make laws to exclude undesirable people from the shores of our country,” she reasons, “can we not make laws excluding the undesirable among the unborn?” Who are these “undesirables?” They are the many children of impoverished mothers, the “poor little disgusting mites who have just ‘growed’ and whose influence is a menace to all other children.”

It was just a joke, of course, an attempt to spice her warnings, as many in my family often do, with a laugh. And yet humor is often the repository for undercurrents of anxiety and violence, especially of the racist category. Iris’ joke is not funny, but it does beg a question, one we can direct both to 1924 and to 2022. As reproductive justice is so unevenly distributed across race, citizenship, and class, who, really, is being menaced, and by whom?

______________________________

Mud, Blood, and Ghosts: Populism, Eugenics, and Spiritualism in the American West by Julie Carr is available via the University of Nebraska Press.

Julie Carr

Julie Carr is the author of eleven books of poetry and prose, including Mud, Blood, and Ghosts: Populism, Eugenics, and Spiritualism in the American West. Her poems and essays have appeared in journals such as The Nation, Boston Review, APR, New American Writing, Denver Quarterly, Volt, A Public Space, 1913, The Baffler, and elsewhere. She lives in Denver.