Like a Magic Trick: Tim Mohr on Being the Translator and Being Translated

On the intersection of German translation, East Bloc punk rock, and Hunter S. Thompson

In December, 2004, I flew to Aspen, Colorado, to stay with Hunter S. Thompson at Owl Farm, his legendary “fortified compound” in nearby Woody Creek. We were supposed to start working on a Gonzo guide to life he planned to write—to be serialized in Playboy magazine, where I was a low-level editor at the time, and then published as a book.

Some visitors to Owl Farm fired guns at books or gas canisters, some partied, and some ran away, too weirded out by the goings-on in Hunter’s orbit. My visit helped kick off a career translating German literature.

It all started with a month-old copy of Der Spiegel, Germany’s biggest news magazine, which contained a profile of Hunter. It bugged him that he couldn’t read it. And things that bugged Hunter were rarely left to simmer quietly on a back burner.

And so, after several days of work—which in this case meant nights of work—on the Gonzo guide to life, Hunter sent me to a central spot in the cabin where his office—which was also the kitchen—opened onto the living room, a space that seemed to be taken up almost entirely by the enormous fireplace. Knowing I’d lived in Berlin, he wanted me to read the Spiegel article and translate it aloud, on the spot, sentence by sentence.

Immediately I struggled to rearrange the German syntax in English, and grew worried as I scanned forward in the piece and caught sight of words I didn’t know.

He stopped me.

Slow down.

Reading aloud at Owl Farm was always regarded as serious art form. Actually, reading aloud was elevated this way wherever Hunter went—I had once witnessed him guide 2003 Playmate of the Year Christina Santiago through passages of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas in a crowded hotel suite atop the Palms Casino in Las Vegas. Even though he himself spoke like a partially-jammed machine gun, sputtering bursts punctuated by unpredictable pauses, with such a jagged and unfamiliar melody that people constantly struggled to understand him, Hunter coached others to give precise, measured, impactful performances.

As I continued to translate, I found my life enriched in ways I wouldn’t have anticipated.Mercifully there were only a few members of his Aspen crew at the cabin that night and the sometimes ornery peacocks were calm. I continued awkwardly rendering the piece into English, trying to work far enough ahead in my mind to formulate passable sentences, sentence worthy of being spoken aloud. When I finally made it to the end, I promised to type up a translation upon my return to New York and send it to him. My first book-length translation—of Guantanamo, by Dorothea Dieckmann—was published by Soft Skull two years later.

As I continued to translate, I found my life enriched in ways I wouldn’t have anticipated. Culinarily, for one. While translating the sly, dark humor of Alina Bronsky’s novels, I started to correspond with her about food and drink references in her work. Before kombucha and kvass became widely available in the US, for instance, I tracked down imported bottles of both at a Russian market in Brooklyn, my curiosity piqued by The Hottest Dishes of the Tartar Cuisine.

Alina expressed her envy—living in a small German town at the time, it had been years since she’d had kvass, which she called “the beverage of my childhood.” When I gushed to her about finding Bashkir honey, Georgian sausages, and a drink made from birch sap—mentioned in her Baba Dunja’s Last Love—she cautioned me: “The birch tree juice is said to have magical properties, and I always felt pity for the trees—thought they (or their spirits) would strike back one day.” I resolved to limit myself to maple syrup.

But it wasn’t until I was struggling to find the right voice for a book of my own, Burning Down the Haus, that I realized how much influence translation would exert on my writing.

*

Hunter used to talk about typing out The Great Gatsby in its entirety in order to get a feel for what a great novel felt like, to experience the physical sensation of typing every letter, hearing every note, and, in Hunter’s case, realizing just how lean Gatsby was. And even though he had repeated this anecdote to me in person, it took many years before I recognized a striking parallel: when you translate, you type out an entire book, too. Though you are also writing it anew at the same time, making the effect perhaps even more extreme: as you translate a book, you don’t just get a feel for it, the book inhabits you.

One translation in particular opened a door for me as I was writing Burning Down the Haus.

My aim was to tell the story of punk rock in East Germany and the role dissident musicians played in fomenting revolution and bringing down the Berlin Wall. Not all the important figures in the scene necessarily wanted to be found. In exchange for one interview, I split a huge pile of firewood in a snowy field, several hours into the countryside north of Berlin.

It was negative-twenty degrees that day (Celsius, but still), and since I hadn’t anticipated doing outdoor labor, I’d shown up with only a wool pea coat and fingerless gloves. Not that I minded the work—my interview partner needed the wood for her off-the-grid cabin. The East German secret police—the Stasi—had jailed her in the 1980s for playing in an illegal punk band, and at some stage after the fall of the Wall she had withdrawn from society.

She wasn’t the only one.

All told, it took me nearly a decade to track down and interview key figures and conduct research for the project. But when I finally went to write the book, I was able to accomplish it in one go, in just a few months. That’s because I had already been writing and rewriting one particular chapter over and over again, a fairly self-contained chapter for which I had most of what I needed early on in the research process. And I had hit upon the right voice for that chapter—and the entire book—after translating a German novel called Tiger Milk, by Stefanie de Velasco.

I’ve always been attuned to the musicality of language, so my starting point for any translation is the aural sensation of the author’s language. Stefanie’s language had a heightened musicality and she wrote with a racing, almost breathless pace. Because of the speed of the language as well as her innovative punctuation, it was never entirely clear whether things were being said aloud or merely thought by the narrator—everything just spilled out. And when I initially began to work on Tiger Milk, I struggled to express the full sonic power of Stefanie’s language in English.

Fortunately, she and I were scheduled to attend a translation workshop together at Art Omi, in upstate New York. I’d never worked directly with an author I was translating, and to be honest I had some trepidation about the idea. But it proved revelatory when I asked Stefanie to read a few short passages of her book aloud one evening. Suddenly the music of her language coursed through me. I practically ran out of the room, intent on trying to translate a particular paragraph of her book while the sound lingered in my ears and my blood seemed to pulse with the music of her writing.

And it worked.

I quickly rendered the passage into English—English that no longer sounded like a tinny imitation of Stefanie, but the real thing. Instinctively I knew I’d now be able to maintain the sound through the entire book. I was so confident that Stefanie and I did anything but work for the remaining days of the workshop. Instead we drove to a barbecue joint in Troy, New York, shopped for ugly holiday sweaters at a strip mall, went searching for the Rogers Book Barn, an obscure bookshop tucked away on a dirt road in Hillsdale, New York.

This was like a magic trick: seeing my thoughts in another language.Back home in Brooklyn—decoupled again from my author—I had no trouble transposing Stefanie’s singular voice into English, just as I’d anticipated. And by the time I’d finished translating Tiger Milk, something magical happened. With Stefanie’s language inhabiting me, I started to figure out ways to express the material in my own book with a similar kind of hyper-musicality.

Originally I’d wanted nothing more than to be a vessel through which the East German dissident voices would pass; now, instead of cut-and-dried exposition punctuated with quotes in standard American magazine style, everything flowed together into a cohesive “sound” more suited to the topic of resistance and revolution.

I’d like to think the book functions like a mixtape or a DJ set, where unique individual sources—the songs in a DJ set; the thoughts and stories of punk activists in my book—are arranged together in a way that creates an atmosphere that is wholly dependent on those sources but in some small way at least also represents something else, something derived from the relationship between the sources. Stefanie’s writing had not only inspired me to better fit the style of my language to the subject matter—it had gotten me there.

*

Burning Down the Haus ended up being published in German first, rather than English. Meaning it would be translated. And not by me, since translators generally go into their native language only.

The German publisher assigned a very well-regarded translator, Harriet Fricke, to the project. We never met in person, but I sent her a note via email: “I hope you will feel free with this translation—the most important thing is to get the rock and roll melody of the language, I think. I really think of all that repetition, for instance, as functioning like drum beats, etc etc. The idea was to take a topic that involves dense and unfamiliar material and tell it in a super-fast way, with real musicality. In addition to the repetition, the language also circles back on itself sometimes. I think in order to mimic the tone of the book, you will need to feel liberated. So go for it!”

Basically, I don’t see translation as collaboration, and I wanted Harriet to know that—and know that I had no aspirations to hover over her shoulder or tinker with her work.

As a practical matter, however, the translation of non-fiction German subject matter into German proved complicated. All the source material—interviews, Stasi reports, interrogation transcripts, diaries, existing German books, samizdat publications, flyers, leaflets, song lyrics, everything—was in German. To a large extent, my book was in itself a translation project—so much so that I’m often asked why I didn’t just write it in German.

The truth is, I hadn’t felt capable of accomplishing in a second language what I wanted to do stylistically. And anyway, the plan all along had been to tell the story to English-language readers—this missing piece of history functioned as a corrective to the American triumphalist view of the end of the Cold War.

The book hadn’t been simply re-written in another language but written anew in another language.It took months to reassemble the book in skeletal form using the original source materials, sending one annotated chapter at a time. The thorniest parts were probably the official East German government documents, which were written in a unique iteration of Beamtendeutsch, or bureaucratic German. If those materials had been simply translated back into German from my English translations, the first East German to pick up the book would immediately have thought, This isn’t authentic.

But eventually the completed German translation, now with the title Stirb nicht im Warteraum der Zukunft, arrived—along with a note from the publisher that said I needed to read through it as soon as possible. Luckily I had a flight from Los Angeles to New York ahead of me, and I figured it was the perfect chance to dig into the draft of the translation.

The plane took off from LAX and steadily climbed until the flight attendants announced that tray tables could now be used.

I cracked open the translation.

Now, I’m accustomed to seeing my writing in German—I routinely trade emails in German, for instance. But this was something different. This was like a magic trick: seeing my thoughts in another language. I say thoughts on purpose, because it wasn’t seeing my words in another language, but my thoughts—the book hadn’t been simply re-written in another language but written anew in another language, creating some other thing, just as a good translation should. Harriet had taken my work seriously enough to do that—to engage with it intellectually, emotionally, musically, and create something out of it in another language. And in this case, in the language of the city that had been the source and the inspiration for the book—a book that had also come to represent my love letter to Berlin.

It was overwhelming.

Tears welled up in my eyes. I started to cry.

That’s when I noticed the woman seated next to me.

Suddenly I could sense her discomfort. She was looking at me only somewhat discretely out of the side of her eye, with her mouth contorted into an expression somewhere between horror and nausea.

Jesus, she must have been thinking, five hours of this shit.

I stopped weeping.

I kept reading.

Back home, I sent an email to the translator, in Hamburg: “I actually cried tears of joy when I first started to read your translation! It was such an emotional experience, as a translator, to read my own work in translation, to hear my thoughts in another language. So thank you very much!”

Harriet wrote back: “Ich bin ein bisschen sprachlos…”

I’m a bit speechless…

I hoped this meant she was touched by my appreciation for her art.

But I also recognized that she could just as easily have typed it with an expression somewhere between horror and nausea.

Had I shared too much?

Luckily, Harriet later elaborated: she’d been caught off-guard, stunned because it was so rare to get a reaction to her work—much less one so “überschwänglich,” as she put it, or effusive.

And in what is a largely invisible profession, that was a feeling any translator could understand.

__________________________________

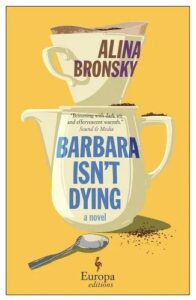

Barbara Isn’t Dying by Alina Bronsky, translated by Tim Mohr, is available from Europa Editions.