The Renegade Ideas Behind the Rise of American Pragmatism

William James, Charles Peirce, and the Questions That Roiled Them

William James and Charles Peirce, friends and the founders of American pragmatism, shared many things: ideas, writings, lectures. And an ongoing flirtation with suicide. Pragmatism, that most buoyant of American philosophies, actually, from the outset, wasn’t buoyant at all. It was born of struggle, of crisis, personal and political, that shook men and women to the core. The clean and well-dressed arguments of contemporary philosophy often mask its less than ideal origins. But when one looks back at what philosophy originally meant in the United States, it is impossible, and indeed disadvantageous, to ignore them.

The American transcendentalism of the 1830s wrestled with the true meaning and value of human independence, in an age that had proclaimed its freedom but didn’t exactly know what to do with it. The pragmatism of James and Peirce inherited this philosophical project and understood its resolution—one that redefined the ideas of autonomy and togetherness—as essential to flourishing in both private and public life. Today, their crises make no small amount of sense, but so too do their respective solutions.

Our own relationship began as a teacher and his one-time student. We’d jog in the woods behind State College, Pennsylvania—the Happy Valley of Penn State—and discuss American pragmatism and why it might give a person a reason to keep running despite life’s obstacles. Over many years, we became friends. Now we are both teachers—one in the belly of his career, one at the tail end. While it didn’t come out in the early years of our relationship, it has become increasingly apparent that we always shared many things: a love of reading, a doubt concerning philosophy’s practical worth, and deep insecurities about life’s value. We were both drawn to thinkers who struggled with the question expressed by William James in 1895: “Is life worth living?” We aren’t exclusively pragmatists, but we agree that James and Peirce still have a great deal to teach us, especially when it comes to this question. Each term we tell our students that philosophy isn’t just an intellectual game. If it is a game at all, the stakes are unspeakably high. Pragmatists such as James and Peirce remind us that philosophy connotes the willingness to live or die—to live and die—for our thoughts. Thoughts matter: they can quicken our end, or help us survive, at least for the time being.

James suffered from depression from his teenage years on, his impulsion toward suicide a visceral reaction to the ancient idea, one pointedly expressed by Ecclesiastes, that “all is vanity”: individuals are always snuffed out before they can make a genuine or lasting mark. For Peirce, a consummate scientist, considering one’s self-destruction was cooler, calmer: a reflective activity brought on by a nagging sense that defined Peirce’s later years that he was of little value to his wife and to society. As he wrote to James in 1905, it is “[my] duty not to allow myself to be a burden upon everybody, even if I have not already become so. It is my duty to get out, to make away with myself. I have considered the question maturely.” More generally, Peirce’s frequent breakdowns coincided with the mounting evidence that he was absolutely alone in the cosmos. Whereas James balked at the idea that single individuals could not effectively exercise their free will, Peirce carefully thought through the meaninglessness of a life lived in perfect isolation.

The existential crises of James and Peirce were grounded in two of the enduring concerns of classical American pragmatism and drove them to concentrate on seemingly disparate, but actually adjacent, concepts: the efficacy of individual freedom and the possibility of genuine communion. They also expressed two different facets of human experience; they embody, in turn, passion and reflectiveness in the face of uncertainty. Their world was not a stable, closed system created by a rational god but an evolving, contingent, precarious temporary home for human animals to make with their neighbors. It was shot through with the risk of real loss. But it was also the home of possibility, a site of making and doing. This was the universe of the pragmatists. The trick was to learn to walk on unstable ground, freely, with others.

It is easy to understand how James acquired his preoccupation with freedom and free will. He was the intellectual godson of Ralph Waldo Emerson, a close friend of his father, Henry James Sr. Emerson’s “Self-Reliance,” delivered in 1832, was regarded, in the words of Oliver Wendell Holmes, as “America’s intellectual Declaration of Independence.” The American Revolution may have secured political freedom, but intellectual and personal freedom was another matter entirely, and Emerson argued that it was high time for his fellow Americans to stand on their own philosophical feet. There was a buoyancy and hopefulness during this time in New England, inspired by belief that freedom could be achieved in more than name only. William James, however, was not born in the midst of this triumphant spirit, but reached intellectual maturity after the Civil War, a conflict that not only shook the nation’s long-standing beliefs in absolutes and transcendent values—as Louis Menand argues in The Metaphysical Club—but also, and perhaps more important for James, cast serious doubt on Emerson’s belief in the power of an individual’s creative spirit.

At the center of his psychological crisis was James’s panic that human action was not free, and therefore that life itself was out of one’s control.

The intellectual climate of America changed in the wake of the Civil War. Gone were the paeans to the sanctity of individual freedoms such as “Self-Reliance” and Thoreau’s Walden, and in their place arose a pervasive faith in the progress of science. Science—measured, calculable, falsifiable science—came to be regarded as the best and safest way to understand the world. Although James’s father was a Swedenborgian mystic, he encouraged his son’s studies in biology and chemistry, and eventually proposed that William become a doctor. William, however, came to have other ideas. Chemistry was dead boring; biology was fascinating but deeply disturbing. Charles Darwin had published On the Origin of Species in 1859, and by the time James considered medical school, Darwin’s friend Thomas Huxley had convinced many intellectuals that humans, like all other animals, were strictly controlled by the forces of nature and that their actions could be exhaustively described by way of physical laws.

The year 1870 was arguably James’s worst. After returning to Cambridge from a biological expedition in the Amazon, he spiraled downward. At the center of his psychological crisis was his panic that human action was not free, and therefore that life itself was out of one’s control. His biological studies did nothing to assuage his fears. “A fact,” he wrote, “too often plays the part of a sop for the mind in studying these sciences. A man may take very short views, registering one fact after another, as one walks on stepping stones, and never lose the conceit of his ‘scientific’ function.” The scientific conceit, James maintained, risked sacrificing the idea that humans could freely choose their own way in life, that the feelings and inclinations, which seem so vividly real, have some causal power. Life could not, should not, be boiled down to the workings of a biological mechanism.

James’s desire for power—his hope that the world could be “up to us”—drew him away from his biological studies, toward a Frenchman who was in the process of constructing a philosophy of free will. Charles Renouvier was an unabashed loner, which might have been at least partially inspired by his argument that the individual will, even in total isolation, could be freely executed. In what became one of the most pivotal passages of classical American philosophy, James wrote in April 1870:

I think that yesterday was a crisis in my life. I finished the first part of Renouvier’s second Essais, and see no reason why his definition of free will—“the sustaining of one thought because I choose to when I might have other thoughts”—need to be the definition of an illusion. At any rate, I will assume for the present—until next year—that it is no illusion. My first act of free will shall be to believe that I have free will.

This philosophical bootstrapping helped James through the “next year,” and the year after that, for the next 25 years, until he wrote “The Will to Believe” in 1896. This essay, published when James was 54, recasts the insight that James gleaned from Renouvier. The proof of free will might be wanting. Perhaps there is no definitive justification of its existence. But to believe and to act as if free will were viable is vitally important. It means believing that one’s life is not determined in advance, that one has at least a modicum of choice over the matter of human existence.

Championing free will and the importance of action, James often suggested pursuing the life of a rugged individualist, and some of his students and friends saw him as just that.

James’s assertion of freedom was coupled with his focus on individuality; he was caught somewhere between the transcendentalism of Emerson and Thoreau that preceded him and the existentialism that followed. Unlike Peirce, James was intent to show the cultural changes that might be wrought by a single individual, and in that vein wrote his lecture “Great Men, Great Thoughts, and the Environment.” And so James concludes in 1896 that “in truths dependent on our personal action, then, faith based on desire is certainly a lawful and possibly an indispensable thing.” Championing free will and the importance of action, James often suggested pursuing the life of a rugged individualist, and some of his students and friends saw him as just that. James’s student Dickinson Miller’s brother visited one of James’s classes and remarked that “He looks more like a sportsman than a professor.”

Peirce was intellectually alone, but he was never mistaken for a rugged individualist. He was a master of self-sabotage, and despite being one of the true philosophical savants of the nineteenth century, could never hold a stable academic position. He was largely despised by his contemporaries (save for James and Josiah Royce) and he lived out his later life in poverty in the hinterlands of northeastern Pennsylvania. Indeed, it was his near-total isolation that led him to the conclusion that James’s Promethean individualism was somehow defective. For Peirce, beliefs were independent, living ideas that helped shape the world; they belonged to no one and to no time and place in particular. The history of the impact of an idea such as “justice” or “truth” was not the work of any one person or any one culture. The meaning and significance of these ideals were evolving and required the work of many people and many cultures. An intellectual, rugged individualism was bound to run aground on local dogma and fad-like creeds.

__________________________________

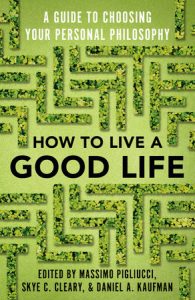

From How to Live a Good Life by Massimo Pigliucci, Skye Cleary and Daniel Kaufman. Excerpted with permission from the publisher.

John Kaag and Douglas Anderson

John Kaag is a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Massachusetts Lowell and author of American Philosophy: A Love Story. Douglas Anderson is a Professor of Philosophy at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. His research interests include History of American Philosophy, Peirce, Philosophy of Religion.