The Quiet

She didn’t hear him arrive.

The wind was up and the rain was thundering down on the tin roof like a shower of stones and in the midst of all the noise she didn’t hear the rattle of his old buggy approaching. She didn’t hear the scrape of his iron-rimmed wheels on the track, the soft thump of his feet in the wet dust. She didn’t know he was there until she looked up from her bucket of soapy water and saw his face at her window, his pale green eyes with their tiny black pin-prick pupils blinking at her through the glass.

His name was Henry Fowler and she hated it when he came.

She hated him sitting there for hours on end talking to Tom about hens and beets and pigs, filling his smelly pipe with minute pinches of tobacco from a pouch in his cracked sheepskin waistcoat, tamping down the flakes with his little thumb, lighting and re-lighting the bowl and sucking at the stem, slurping his tea and sitting there on the edge of his chair like a small observant bird, and all the time stealing glances at her and looking at her with his sharp eyes as if he could see right through her. It filled her with a kind of shame. She felt she’d do almost anything to stop Henry Fowler looking at her like that, anything to make him leave and clear off back to his end of the valley. It felt like the worst thing in the world to her, him looking at her the way he did.

He was looking at her now on the other side of the glass, blinking at her through the falling rain. She wished she didn’t have to invite him in. She wished she could send him away without asking him in and offering him a cup of something, but he was their neighbour and he had come six miles across the valley in his bone-shaking old buggy and the water had begun to pool around the brim of his old felt hat and drip onto the shoulders of his crumpled shirt. It was bouncing back up off the ground and splashing against his boots and his baggy serge trousers. She would have to offer him a chair by the stove for half an hour, refreshment. A cup of tea at least. She wiped her soapy hands on her skirt and went to the door and opened it and called to him.

‘You’d better come in Mr. Fowler. Out of the rain.’

* * * *

Her name was Susan Boyce and she was twenty-six years old. It was eight months now since she and Thomas had sailed out of Liverpool on their wedding day aboard the Hurricane in search of a new life. It had excited them both, the idea of starting from nothing. They’d liked the razed, empty look of everything on the map, the vast unpunctuated distances, and at the beginning of it all she hadn’t minded that the only company was the sound of the wind and the rain and the crackle of the dry grass in the sunshine. At the beginning of it all, she hadn’t minded the quiet.

She hadn’t minded that when they’d arrived in the town they’d found nothing more than a single dusty street. No railway station and no church, only an empty hotel and a draper, a dry goods store that doubled as a doctor’s surgery, a smithy and a pen for market day. She hadn’t minded that when they’d ridden out twelve miles into the parched country beyond the town they’d found rocks and gum trees and small coarse bushes and the biggest sky she’d ever seen and in the middle of it all their own patch of ground and low, fallen-down house. She hadn’t minded that there weren’t other farms nearby, other wives. She hadn’t minded that there was no one but Henry Fowler, who lived six miles off and had no wife. No, she hadn’t minded any of it and wouldn’t now, she was sure, if things with Tom were not as they were.

Now she wished there was another wife somewhere not too far away. Someone she might by this time have come to consider as a friend; someone she might be able to bring herself to tell. But there was no such person. There was her married sister in Poole who she could write to, but what good would that do, when it might be a year before a reply came? A year was an eternity; she didn’t think she could last a year, and even then, she wasn’t really sure she could get the thing down on paper in the first place.

Once, a month ago, when she and Tom had gone into town and he was off buying nails, she’d got as far as the black varnished door of the doctor’s consulting room in the dry goods store. She’d stood there outside it, gripping her purse, listening to the low murmur of a woman’s voice on the other side of the door and she’d tried to imagine her own voice in there in its place and she couldn’t. She just couldn’t. It was an impossible thing for her to do. What if the doctor said he had to speak to Thomas? What then?

If there’d been a church in town, she might have gone to the priest. A priest, she thought, might be an easy person to tell; but even there, she wasn’t sure what a priest would say on such a matter. What if he just told her to go back home and pray? Would she be able to tell him that she’d tried that already? That every night for more than half a year she’d lain in bed and prayed till she was blue in the face and it hadn’t worked? Anyway it was a waste of time to think about a priest because there wasn’t a church for a hundred miles. It was a godless place they’d come to. Godless and friendless and only Henry Fowler’s wizened walnut face at her window at nine o’clock in the morning, poking his nose into her private business.

Well she would not sink under it. No she wouldn’t. She’d experienced other setbacks in her life, other disappointments and shocks of one sort or another. It would be the same with this one, she would endure it like anything else, and wasn’t it true anyway, that in time all things passed? This would too. There was a remedy, in the end, for everything. She just had to find it.

* * * *

When she and Fowler were inside she told him that Tom had gone into town for salt and oil and needles and wouldn’t be back till nightfall. Fowler nodded and asked if he might tip the water from his hat into her bucket of soapy water.

‘Of course,’ she said—cold, prim, barely polite.

She invited him to sit, and said she would boil the water for some tea.

At the stove she busied herself with the kettle, wondering what he wanted, why he’d come. She wondered if he was going to sit there and look at her in that way of his that made her want to get up and go somewhere away from him, into a different room, behind a door or a wall or a screen, so he couldn’t do it. Somehow it made everything worse, being looked at, especially by someone like Henry Fowler. She’d rarely seen any one who looked as seedy as he did. She wondered if he’d been a convict.

He’d visited them three times before now, once not long after they’d arrived and then again a few months after that, and then a third time just last week. Each time he’d come wearing the same grimy outfit, the same crumpled shirt and ancient sheepskin waistcoat, the same greasy serge pants, the same bit of cotton rag about his thin neck. The only thing she noticed that was different about him today was that he seemed to have brought nothing with him; whenever he’d come to visit them before, he’d always brought some kind of neighbourly gift. The first time it had been a quarter pound of his own butter, the second time a jar of pumpkin seeds. Last time, a loaf. This time his small weather-beaten hands were empty; today Henry Fowler seemed to have brought nothing but himself.

* * * *

He was forty-five years old—a small, scrawny-looking man with bow legs and rough brown hands no bigger than a woman’s.

At sunrise he’d stood with one of those hands resting on the wooden rail of his rickety veranda at the far end of the valley, watching his new neighbour’s black horse and dray moving slowly along the road in the direction of the town, wondering if the handsome husband was travelling by himself—if the young wife would be alone there today.

It was six months now since he’d watched them come in on the same road with a pile of furniture tied onto the dray. Since then he’d seen her three times. Three times he’d gone over there with a neighbourly gift. Three times he’d walked about outside with the husband, admiring the progress they’d made. The beets and peas and beans, the potatoes and the fat new pigs. The two hundred chickens, the cow. Three times he’d sat with the two of them inside the house drinking tea and for weeks now he’d been spending the evenings sitting on his veranda and looking out across the grassy desert towards their place.

Susan. That was her name. Susan Boyce. For weeks he’d been thinking about her and practically nothing else. Her stiff, cold, proud-looking face, the closed-off, haughty way she had of speaking to him, the way she couldn’t stand him looking at her.

When he could no longer see the dray on the horizon, when it had disappeared completely from view, he went inside for a while and then he laced up his boots and put on his hat and climbed up onto the seat of his high sloping buggy and set off along the track down the valley to her house.

* * * *

He sat now, at her table, tamping the tobacco into the bowl of his pipe with his little thumb, watching her at the stove.

It’s true that Henry Fowler still had the look of a convict about him. He had the look of an old sailor too, and of a fairground monkey someone had dressed up in a pair of pants and a waistcoat and an old felt hat. He was small and sun-wizened and ugly and as he sat now, listening to the wind and the rain and the snuffling of Thomas Boyce’s pigs and the crackle of the fire in the stove and the simmering of the water in the kettle on top of it, he was sure he could also hear the beating of his own heart.

The fact is, Fowler was even more nervous now that he was here than he’d expected to be.

His sheepskin waistcoat creaked; he didn’t know where to begin. He’d rehearsed everything before he came, had stood for an hour or more before the mirror looking at his own half-naked body, and it had all gone smoothly enough. The words had come without too much difficulty. Now, looking at the other man’s wife standing at the stove with her slender back turned towards him, they escaped him.

He took a few quick puffs on his pipe and decided the best thing to do would be to undress.

He took off his waistcoat and placed it over the back of the chair, unknotted the grimy square of cotton he wore folded around his throat and laid that on top of the waistcoat. He undid the buttons on his crumpled linen shirt until the whole thing was hanging down from the canvas belt that held up his trousers, and at that moment Susan Boyce turned. She turned and screamed and dropped the teapot, and covered her mouth with her hand.

Henry Fowler’s narrow pigeon chest was lumpy and shrivelled like the map of some strange unknown country. It had a kind of raised border all around it that was ropy and pink; inside it the skin had a cooked, roasted look to it—it was blackened and leathery and hard, like a mummy’s, or a creature that has lain for a thousand years in a forgotten bog.

He turned. Three dark triangles the colour of ripe Victoria plums decorated his shoulders; below them and covering most of the rest of his back was another dark shape, also plum-coloured—the puckered print of something large and round.

Low on his hip, just above the canvas belt that held up his trousers, there was a firework splatter of a dozen deep, wrinkled divots.

‘My wife,’ said Henry Fowler, the words finally coming to his rescue, ‘was bigger than me.’

Looking down and behind at his own ruined body he explained how he’d got his blackened chest (a jug of boiling water from the copper), the three dark triangles on his back (her smoothing iron), the big round brand beneath them (the frying pan), the divots (the red-hot poker), and then with his voice dropping very low he told Susan Boyce that there was something else too, below his canvas belt, but he would not show her that. No. If she wanted to guess the worst thing a bad-tempered wife might do with a pair of sharp-bladed dress-making shears, then she would have it.

Susan Boyce said nothing, only looked.

‘She is under the beets,’ said Fowler quietly—one night when she was sleeping he’d stabbed her through the heart with the sharp stubby blade of a paring knife and carried her outside and buried her with all her things: her skirts and her clogs and the pins from her hair, her frying pan and the jug from the old copper, her iron and the poker and the cutting-out shears and everything else she’d ever owned or touched that reminded him of her and might make him think she was coming for him again—anything that might make him think he could hear the clatter of her furious clogs charging towards him across the hard clay floor.

In town, he said, he’d put it about that she’d run off and left him.

Susan Boyce looked at him.

Her face was still, without expression, and Henry Fowler thought to himself, I have made a mistake. I am wrong about it all.

He had been so sure before but now that he was standing in front of her with his waistcoat over the back of the chair and his neck-cloth lying on the seat and his shirtsleeves hanging down like a skipping rope between his knees, Henry Fowler said to himself: I have watched her here in this house, moving about in her shawl and her plain high-necked gown, passing behind his chair and pouring his tea, and I have caught the scent of something that isn’t here, and when he returns tonight she will tell him what I have told her and he will fetch a few of the men from town and they will come with their shovels and dig under the beets and they will look at the marks on me and I will tell them how I got them and they will look at each other and remind themselves that Henry Fowler is nothing but a seedy old convict with a bit of land to his name and they will shake their heads and call me a liar and then they will hang me.

He began to scrabble between his bandy legs for the cuffs of his shirt, telling himself that as soon as he was dressed he would climb up into his old buggy and head off back up the valley and once he was home he would think about what to do, whether he should sit there on his veranda and wait until they came for him, or if he should leave tonight and go somewhere they wouldn’t be able to find him, or if he should come back in the morning and talk to Boyce and explain things to him in his own words so he would understand. He bent to the chair where he’d laid his clothes and picked up his neck-cloth, looped it behind his dipped head and pushed his arms into the sleeves of his dangling shirt, and he would have left then, probably without saying another word, probably just reaching out for his hat and heading for the door, but by the time he’d raised himself again and looked up into the room to where Susan Boyce was standing, she had begun to unhook her bodice.

She was loosening her skirt and pulling her chemise over her head and undoing the tapes of her petticoats and then she was letting the whole lot slide to the floor around her feet on top of the broken remains of the teapot and its lake of cooling water until she was standing before him in nothing but her woollen vest and her cotton drawers, and then she was taking those off too. She did it quickly, hurriedly, as if she thought she might never again get the chance to show him, as if she thought, even now, he might not be on her side.

She looked smaller, without her clothes, different in every possible way, turning in front of him, displaying the split, puffy flesh of her thighs and buttocks, the mottled green, black and yellow of her belly, the long, weeping purplish thing that started under the hair at her neck and ran down the back of her like a half-made ditch. She came towards him, stepping through the puddle of tea and over the piled-up heap of her things. She took his small brown hand and lifted it to her cheek and closed her eyes like someone who hadn’t known till now how tired they were, and then she asked him, would he help her, please, to dig the hole.

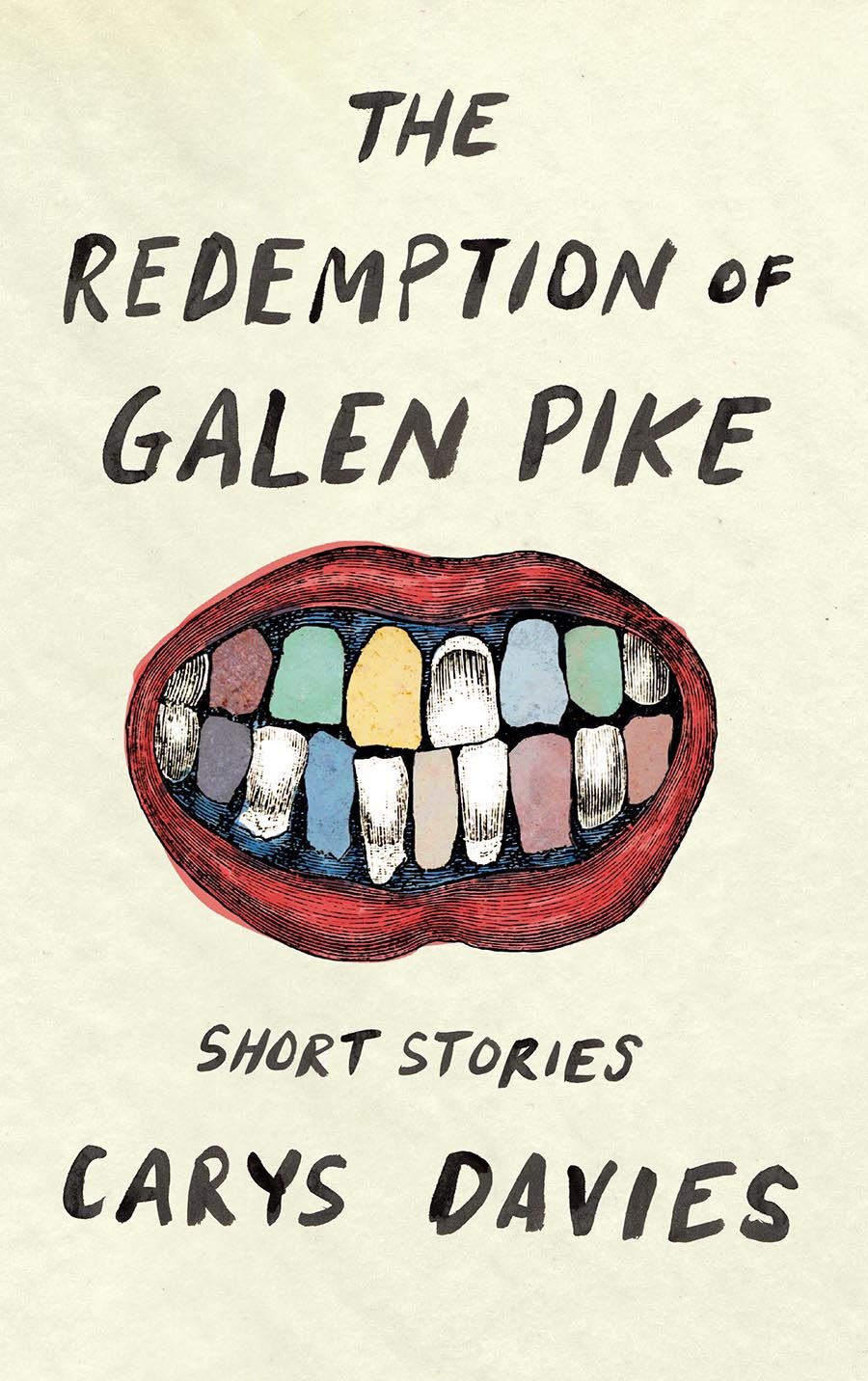

From THE REDEMPTION OF GALEN PIKE. Used with permission of Biblioasis. Copyright © 2017 by Carys Davies.