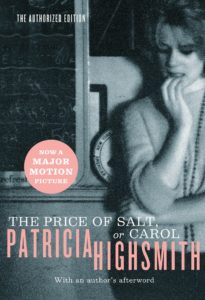

The Rapturous Love of Patricia Highsmith’s Carol

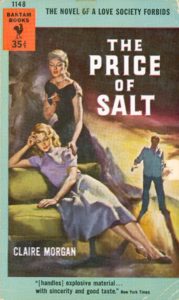

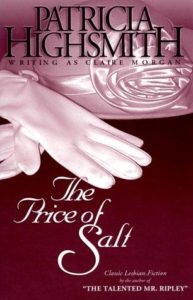

A Classic Review of Highsmith’s Groundbreaking Lesbian Romance Originally Published as The Price of Salt in 1952

It would be Carol, in a thousand cities, a thousand houses, in foreign lands where they would go together, in heaven and in hell.

*

“The heroine of this tale of lesbian love is a lonely 19-year-old, who has been brought up, more or less as an orphan in a semi-religious ‘home.’ At the novel’s opening, Therese Belivet has been working for two years in New York, trying to save $1,500 for membership in the stage designer’s union. Her attempts at an affair with the young man who wants to marry her have been a failure; and she knows that she does not really love him. When she meets Carol Aird—a beautiful, wealthy, sophisticated woman of 30, who is in the process of divorcing her husband—Therese falls totally in love at first sight.

“Radiantly happy in Carol’s company, Therese cannot conceive of there being anything questionable about this new relationship. When the two women take a motor trip to the West, it is Therese who, with pure blind innocence, causes them to become loves. And she thereby precipitates a crisis in which they both have to make decisions that will lastingly affect their lives.

“Obviously, in dealing with a theme of this sort, the novelist must handle his explosive material with care. It should be said at once that Miss Morgan writes throughout with sincerity and good taste. But the dramatic possibilities of her theme are never forcefully developed. While Therese’s rapturous love sometimes gives a glow to the story, the novel as a whole—in spite of its high voltage subject—is of decidedly low voltage: a somewhat disjointed accumulation of incident, too much of which is pretty unexciting as story-telling and does little to deepen insight into the characters. Therese herself remains a tenuous characterization, and the other personages are not much more than silhouettes. This reader’s interest was always on the verge of being awakened—and never quite was.”

–Charles J. Rolo, The New York Times, May 18, 1952

Book Marks

Visit Book Marks, Lit Hub's home for book reviews, at https://bookmarks.reviews/ or on social media at @bookmarksreads.