The Radical Power of a Bookstore: On Lawrence Ferlinghetti and City Lights

Gioia Woods Reflects on the Life of a Literary Icon

I discovered City Lights Bookstore in 1983. I was a high school sophomore in east Los Angeles on a campus so diverse that you would be just as likely to hear kids speaking Spanish or Vietnamese as you would English. Most of us were the children or grandchildren of immigrants. The school was poorly funded, riven by gang violence, and deeply segregated by race and class. We read Hemingway and Shakespeare in English class, literature that meant little to us. It was the place I fell in love with language.

My drama teacher Mr. Heap surfed every morning just south of the nuclear plant at San Onofre before coming to work. We’d see him in the upper parking lot before class, settling his board in his VW van and balancing stacks of books in his arms to bring into class.

One day among the stacks on his desk I noticed a staple-bound, signed copy of Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s 1979 poem “The Old Italians Dying.” I picked it up and was shocked to see people I recognized. In a poem! There they were, “the old Italians in faded felt hats… the old Italians in their black high button shoes… the old ones with gnarled hands / and wild eyebrows / the ones with the baggy pants with both belt & suspenders… the ones who loved Mussolini / the old fascists.” My own nonno was a fascist, a Mussolini man, a pilot who had been shot from the sky while flying an imperial mission over Ethiopia. As a kid I was perennially embarrassed by him, and by my immigrant mom. Mama said “engine fire” instead of “fire engine” and kept a pot of minestrone on the stove as an afterschool snack.

This singular act of reading the “Old Italians” produced in me what I now understand (thanks to literature scholar Derek Attridge) as an event that moved me “beyond the possibilities pre-programmed by a culture’s norms.”

I asked Mr. Heap about this guy Ferlinghetti. He owns a bookstore in San Francisco, Heap said. And that was it. As soon as I got my driver’s license, I made the first pilgrimage to City Lights Bookstore.

Decades later, in June 2015, I met Lawrence Ferlinghetti in his North Beach walkup. At his kitchen table he recalled a Pier Paolo Pasolini tribute reading in Ostia where the crowd was shouting for minestrone. I read some of his mail out loud to him (his sight was significantly diminished), mostly from journal editors requesting reprint permissions for his paintings. Before I left, I helped him roast a chicken he’d prepped for dinner. He was fretting over his new oven and an NPR interview he’d just recorded. The next day I asked him about the interview and the chicken: “The chicken turned out just right,” he responded, “nice and juicy… The NPR interview was cut to the bone, not much left to it.”

How could a short interview possibly capture Ferlinghetti’s capacious curiosity and commitment to literary activism? As the co-founder of what may be the most famous independent bookstore in the country, how could an interview fully describe the impact of his work and the ongoing, vibrant impact of the institution he helped establish?

City Lights helped democratize reading; it promoted what Attridge describes as an “accumulation of individual acts of reading and responding” which causes “large cultural shifts.”

Ferlinghetti was an orphaned child of immigrants, a self-proclaimed anarchopacifist, and a GI-Bill funded doctoral student at the Sorbonne. From his arrival in San Francisco in 1951 to his death on February 22, 2021, he was a poet, painter, critic, editor, activist, translator, and business owner. He was one of the most important public intellectuals of his day, an uncompromising champion for literature’s power, freedom of expression, and the necessity of both to democracy.

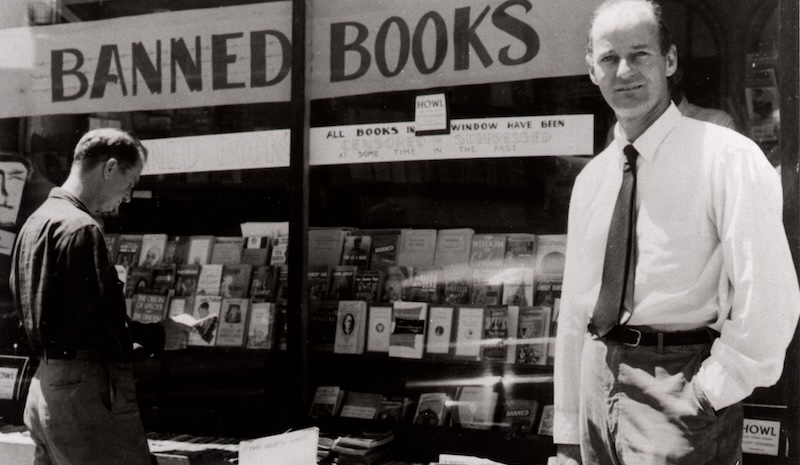

Even as our civic institutions suffer, independent bookstores like City Lights have become stronger. And we need them now, more than ever. Universities are under threat of government interference, book banning has reached unprecedented levels, journalists and artists and media outlets and attorneys are being punished, silenced, and doxed, and dissent everywhere is being criminalized.

How, against all odds, has City Lights managed to remain a vital symbol of literary dissent and free speech? How, after more than seventy years, has City Lights survived economic and industry changes? How, decade after decade, has it managed to respond to the forces that threaten to silence us? How, decade after decade, did it confront the Cold War, the suppression of civil rights, various ecological crises, American intervention in Latin America, the AIDS epidemic, mass incarceration, consumer capitalism, and the global rise in tyranny? These are the questions I take up in my book City Lights: Lawrence Ferlinghetti and the Biography of a Bookstore.

The bookshop was co-founded in 1953 by Ferlinghetti and Peter Martin. Martin was the son of an assassinated Italian labor organizer. He worked part-time as a sociology instructor while editing a little magazine called City Lights. Martin had recently published three poems by a fellow named Lawrence Ferling. Ferlinghetti, who had not yet adopted his immigrant father’s original name, was an aspiring painter, poet, and freelance art critic.

*

With a handshake and a $1,000 investment, City Lights became the first all-paperback bookstore in the country. Stocking only paperbacks was a radical choice. Bookstores were still, in many communities, elite institutions carrying hardbound books for wealthy customers. “One of the original ideas of the store,” Ferlinghetti explained, “was for it not to be an up-tight place, but a center for the intellectual community, to be non-affiliated… We were open seven days a week till midnight, and we literally could not close our doors at closing time. We seemed to be responding to a deeply felt need.” City Lights helped democratize reading; it promoted what Attridge describes as an “accumulation of individual acts of reading and responding” which causes “large cultural shifts.”

Martin left San Francisco in 1955, and Ferlinghetti launched City Lights Press and its signature Pocket Poets Series. His own Pictures of the Gone World became number one in the series. It was not until 1957 when he published Number Four, Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems that Ferlinghetti began making a name for himself as a canny editor, courageous publisher, and fiercely independent advocate of freedom of expression.

The results of the subsequent Howl obscenity trial are well known: San Francisco Ninth Circuit Judge Clayton Horn ruled that the poem, despite its crude language and allusions to homosexuality, possessed “redeeming social importance.” Judge Horn wrote,

The first part of “Howl” presents a picture of a nightmare world; the second part is an indictment of those elements in modern society destructive of the best qualities of human nature; such elements are predominantly identified as materialism, conformity, and mechanization leading toward war.

As a poet, publisher, and public intellectual, Ferlinghetti spent the rest of his career resisting the very torments Judge Horn said haunted the post-war world.

True to its founding fight over censorship and book banning, the institution remains a bastion dedicated to the transformative power of the book. When she accepted the National Book Critics Circle Toni Morrison for Achievement Award on behalf of City Lights in 2022, executive editor Elaine Katzenberger described a current “atmosphere of intimidation and the attempt to control what we are able to read.” Katzenberger invoked City Lights’ history as well as its ongoing commitment to freedom of expression: “[T]his is not the first time that those who seek power have attempted to gain it by limiting access to knowledge and ideas.”

This is how City Lights remains relevant even after seventy years. The institution is a cultural first responder that documents the effects of materialism, conformity, and mechanization. It collects the evidence and provides comfort and hope to its victims. Diane DiPrima captured its relevance in her 2014 poem “City Lights 1961”: “And dig it, City Lights still here, like some old lighthouse” where “crowds of people still haunt the stacks / seeking out voices from all quarters / of the globe.”

I love how DiPrima characterizes City Lights Bookstore as a lighthouse; signaling, warning, illuminating what threatens our civic life. I love how the poem acknowledges the way it continues to promote the world’s literature, publishing and promoting voices from “all quarters of the globe.” And mostly, what inspired me to write the biography of this institution, I love the resounding fact of City Lights being “still here,” still celebrating language in all its power and diversity.

__________________________________________

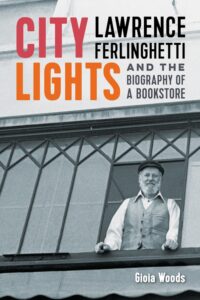

City Lights: Lawrence Ferlinghetti and the Biography of a Bookstore by Gioia Woods is available via The University of Nevada Press.

Gioia Woods

Gioia Woods is professor of humanities and chair of the Department of Comparative Cultural Studies at Northern Arizona University. She is the author of the Western Writers Series monograph Gary Paul Nabhan, coeditor of Western Subjects: Autobiographical Writing in the North American West, and editor of Left in the West: Literature, Culture, and Progressive Politics in the American West.