The Race to Save a Medieval Palestinian Library

Ryan Byrnes on the Khalidi Family’s Battle to Protect Their Library From Ultra-Orthodox Settlers

While the golden Dome of the Rock sweltered under one-hundred-degree heat a gang of heavily armed orthodox Israelis marched on a Palestinian library. Brandishing forged documents falsely claiming their ownership of the building, they enlisted the help of Israeli police in smashing the locks and entering by force. The ultra-orthodox group, with their leader Eretz Zakay, had a long history of illegally seizing Palestinian property across Jerusalem.

News of the break-in, which happened June 27, 2024, made its way to the Khalidi family, the chief caretakers of the library stretching back to the Ottoman period. For Palestinians in Jerusalem, property seizures are all too common. Oftentimes the justice system provides legal cover for this theft rather than any kind of meaningful reparation. Bracing herself for what was to come, the family’s legal representative Sana Doueik gathered paperwork and rushed to the scene.

While Sana argued with the police in the street, the ultra-orthodox settlers rampaged through the library. Word of the break-in spread like wildfire through the neighborhood, and soon a crowd of enraged Palestinians congregated in support of the Khalidis. Israeli police officers watched as the increasingly irate crowd edged closer, threatening to break the illusion of control they had so carefully established. They proceeded to beat back the Palestinian protesters, landing blows on their heads.

As night fell over Jerusalem, the settlers still had not vacated the library. While illegal, their occupation nonetheless animated plenty of supporters. An ultra-orthodox school sat adjacent to the library, and its staff supplied the settlers with sleeping mats and air conditioning for the long night.

Library roof with Dome of the Rock. Photo by Issa Freij, khalidilibrary.org.

Library roof with Dome of the Rock. Photo by Issa Freij, khalidilibrary.org.

If the police officers had listened to Sana Doueik that afternoon, they would have learned something important: the Khalidi Library constituted a waqf, which in Islamic law is an unbreakable endowment passed down through the generations. The Khalidi family are legendary in Jerusalem. Calling the city home since the Crusades, they have built a dynasty that includes preeminent historians, economists, and even United Nations diplomats. Today, three Khalidis sit on the board of library administrators: Raja, Asem, and Khalil.

The Khalidi Library represents everything the settlers cannot abide. It is a monument to, and repository of, the history and heritage of a culture they claim should not exist.

I got the chance to speak with Raja Khalidi, who, when not running the library, is also the Director General of the Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute. He hopped on a video call from his office, recounting these events between drags of his cigarette. According to Raja, his family started the library during the Ottoman period, when they made their personal book collections available to the public. This was the first Arab public library in Jerusalem established by private initiative.

“At first it was established for scholars and judges and clerks in Jerusalem,” Raja explains, “because it is literally on the road leading up to the Dome of the Rock where these officials would go to pray five times a day.” Dignitaries would climb up Bab al Silsilah, a narrow limestone street that ducks under an arched gate. Further down, the street opens onto the broad plaza before the Haram al-Sharif, or the Temple Mount—the city’s beating heart.

In the thirteenth century, the site became a cemetery for warriors who fought in the Crusades. Over time, the library buildings expanded to encompass the cemetery, with the Crusade-era gravestones embedded in the flagstones.

Medieval cemetery remains. Photo by Issa Freij, khalidilibrary.org.

Medieval cemetery remains. Photo by Issa Freij, khalidilibrary.org.

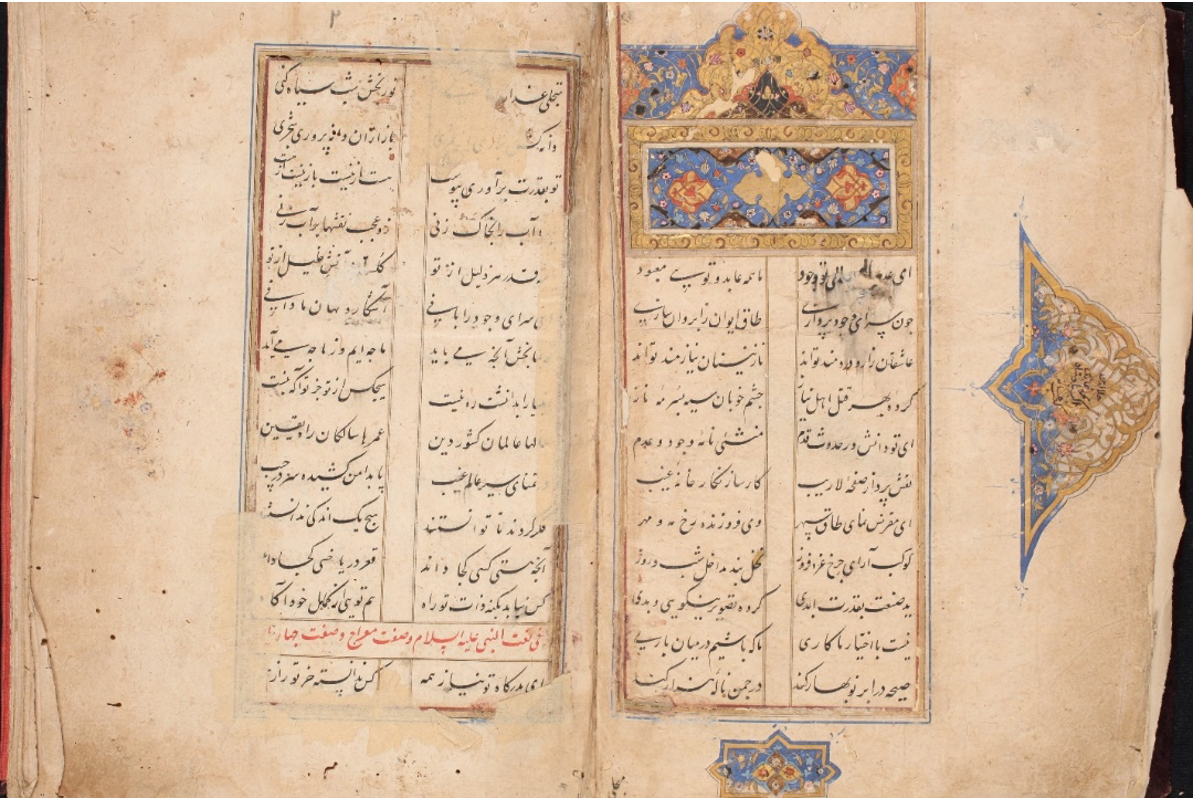

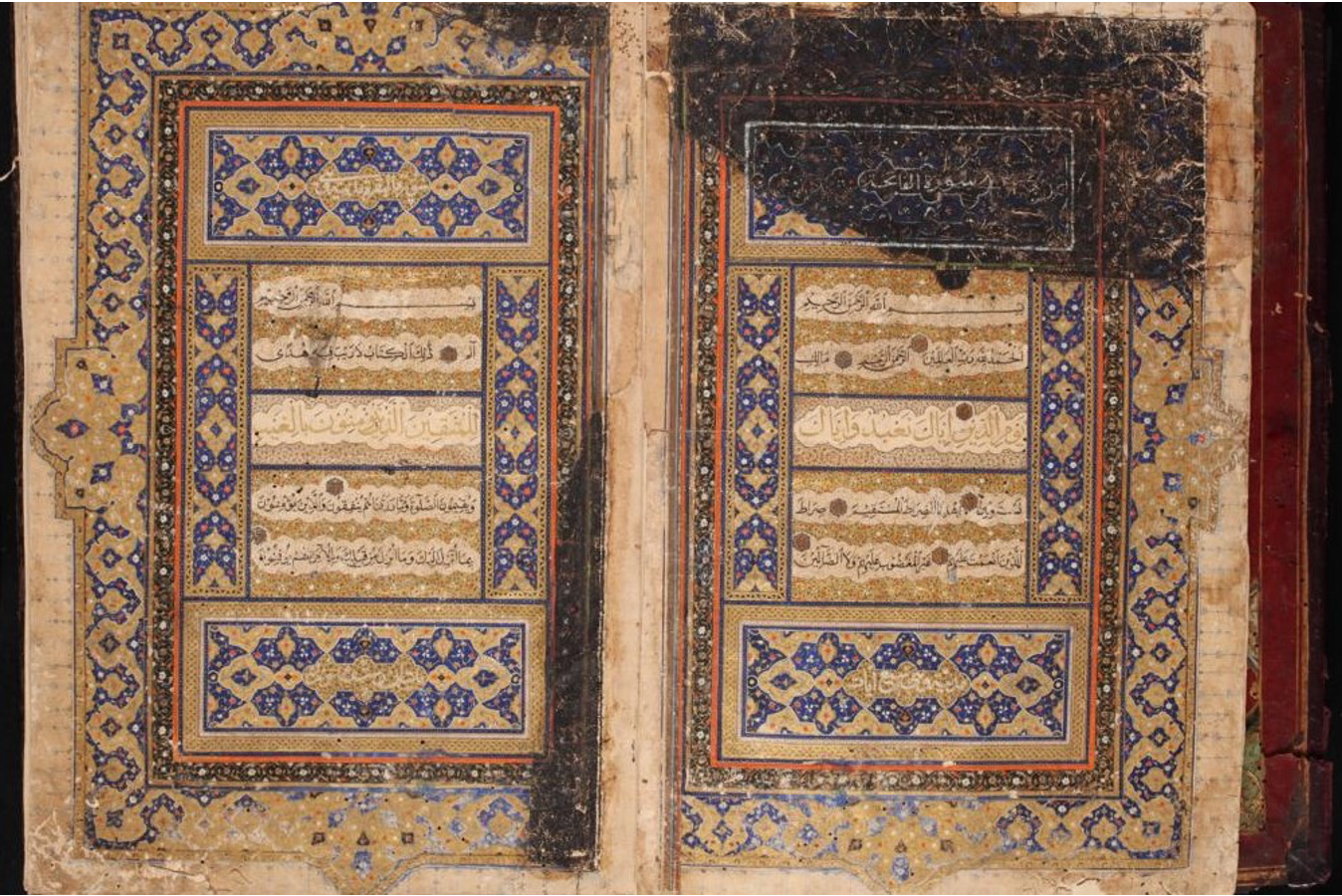

Venture further into its vast archives, and visitors will find over one thousand handwritten medieval manuscripts, fully illuminated with gold leaf, floral motifs, and winding Arabic calligraphy. The most sought-after manuscript features a vividly illustrated depiction of the Battle of Hattin from the Crusades.

Persian Manuscript, The Lover and the Beloved, khalidilibrary.org.

Persian Manuscript, The Lover and the Beloved, khalidilibrary.org.

Quran, 16th century, khalidilibrary.org.

Quran, 16th century, khalidilibrary.org.

In addition to its medieval manuscripts, the library catalog is a treasure trove of more recent history. The Khalidi family, with their lineage of scholars and diplomats, have had a front-row seat to the modern Palestinian struggle. They have amassed one of the largest collections of legal documents detailing their nation’s 77-year fight against Israeli occupation. Despite continual risk to the library’s existence, scholars from across the world still travel there to conduct research. Some may recognize the name Rashid Khalidi, Columbia professor and bestselling author, who used the library’s archives when writing his New York Times bestseller, The One Hundred Years’ War on Palestine.

Ultra-orthodox settlers have have made the library a target of attack since the 1960s. Why such animosity towards books? Perhaps because the Khalidi Library represents everything the settlers cannot abide. It is a monument to, and repository of, the history and heritage of a culture they claim should not exist.

Life of the Prophet, dated 1511, khalidilibrary.org.

Life of the Prophet, dated 1511, khalidilibrary.org.

After enduring a sleepless night while the settlers slept on their library floor, the Khalidi family regrouped in the morning. Recent years have seen thousands of Palestinian properties illegally seized, but the Khalidis would not be taken for fools. Generations of occupation have taught them every facet of the Israeli legal system. Fortunately, the break-in occurred on a Thursday. “Had the occupation happened on a Friday, the courts would have been closed,” Raja explains.

Raja, along with other library custodians and their legal representative, filed into the Israeli Magistrate Court to request an eviction order on the settlers. The settlers’ defense rested on documents presented in April 2024 to a district court showing their ownership of the library. There was one problem, however: the court discovered that Israeli notary publics had forged the documents. They had no legitimacy. According to a press release from the library, the Israeli magistrate judge “issued a preliminary order to evict the settlers immediately and to permit the Khalidi family to change the lock.” The judge ordered another hearing for Sunday, but until then the keys to the library would remain with the police. The Khalidis were locked out of their own property.

The Book of Shanaq on Poisons and Antidotes, khalidilibrary.org.

The Book of Shanaq on Poisons and Antidotes, khalidilibrary.org.

Friday and Saturday passed with the library’s fate in limbo. Finally, on Sunday, the Magistrate Court issued an official ruling. As Raja explains, “The judge sought more details, realized what was going on, realized the library had well-established paperwork from Israeli courts, and gave us back the keys to the library.” The settlers appealed multiple times, but they did not even show up to their own court date because they knew their case was indefensible.

They had achieved an exceedingly rare victory: convincing an Israeli judge to return stolen Palestinian property.

This was not the family’s first experience with squatters. In 1968, a group of ultra-orthodox Israeli settlers illegally seized one of the central library buildings, effectively cutting the campus in two. The Khalidi family received no hearing, no court date, no due process. The famous Rabbi Shlomo Goren transformed the building into a Yeshiva, or Jewish school. The Palestinian library and the Yeshiva stood side-by-side for decades, as if encapsulating the last hundred years of their history, all under the looming shadow of the Temple Mount.

The standoff continued into the 1990s, when the library started to show its age. This prompted Professor Walid Khalidi, a renowned historian and custodian of the library who turned 100 last June, to establish Friends of the Khalidi Library. The group is now a registered 501c3 nonprofit and raises funds to pay for the librarian, the security guard, and other overhead costs. They also received contributions from the Ford Foundation, the government of the Netherlands, and the Arab Fund, to restore the library.

By the early 2010s, a new board of custodians was appointed, one which included Raja Khalidi. They received grants from the British Council, the Aliph Foundation, and the Arab Fund to digitize their library. A group from Minnesota called HMML digitized all their manuscripts for preservation, a major project that involved taking over 500,000 images which are now available for free online for everyone to appreciate.

Digitization process, posted on Khalidi Library Facebook page January 14, 2022.

Digitization process, posted on Khalidi Library Facebook page January 14, 2022.

Raja smiles as he recalls that fateful Friday afternoon. After twenty-four hours of chaos, the gang of Israeli settlers exited the library’s medieval arches for good. “From the first moment, we knew we would win it,” Raja tells me. “We knew we had the paperwork to prove our case. Within hours the judge had our paperwork and knew the settlers’ claim was bogus.” They had achieved an exceedingly rare victory: convincing an Israeli judge to return stolen Palestinian property.

“There was a mass feeling of ‘Wow, we can do it!’” Raja says. “If it was a normal country, the police would have taken action against these people who the judge clearly identified as having done some seriously shady stuff.” When given the option to sue the settlers for damages, the Khalidis declined. They didn’t want to provoke any further confrontation with their neighbors, Raja explains. Just keeping their library was enough.

In December 2024, the library received a second ruling from the very same district court that had originally enabled the settlers to take over. After realizing the ruling was based on forged documents, the district court annulled its previous decision. Currently, the library survives, but threats remain. Settlers continue to harass and intimidate its staff.

The modern era has seen libraries increasingly pulled into the crossfire of war. Being profound symbols of national identity, they are often primary targets by those seeking the destruction of certain groups. In 1992, the Serbian military burned down the National and University Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina, torching thousands of historic manuscripts. In 2015, the terrorist group ISIS leveled the library of Mosul along with over 100,000 books. More recently, the Russian military has damaged or destroyed over 790 Ukrainian libraries. Libraries douse the destructive flames of ignorance. Knowledge, free to the public, cannot coexist with the ambitions of terrorists.

The settlers spent one night in the library. If they had bothered to read any of its books, they might have learned something: Palestine exists. If you need proof of that fact, look no further than the perseverance of its people.

Ryan Byrnes

Ryan Byrnes is a book editor at Springer Nature. His first novel, Royal Beauty Bright, won an Independent Publisher Book Award while his second novel, My Dear Antonio, was published in 2024. His writing has also appeared in New York Journal of Books, Italian America, December, Pembroke, and more. He lives in Brooklyn. As a young writer beginning his career, he hopes to continue learning the craft and helping others tell their stories.