The Quiet Renaissance of India's Community Cookbooks

A Plea For Regional Flavor Rises in the Era of Prepackaging

My mum is a kitchen conjurer. You never know what will spill out of her kitchen on any given day. Today it might be coconut-spiked green gram, Maharashtrian Saraswat style. Tomorrow it might be shrimp and pumpkin relish, cooked Bengali style. The day after, perhaps Andhra hyacinth bean curry, or maybe even Tellichery biryani, the way they do in Kerala. For these marvels, we have to thank the fleet of cookbooks that are hovering in my book cabinets.

We are habituated to reading cookbooks as a work of exacting precision, whose ambition is the elimination of subjectivity. But they also debouch into culture, society and anthropology, mapping stories about a particular culture. As the publishing industry’s view of Indian cuisine approaches homogenization—as ingredients and cooking methods are universalized, regional ingredients cut from cookbook recipes, and individual inflections flattened—recent years have seen a quiet renaissance of cookbooks focused on particular communities and geographies of India. Some are published privately by earnest ladies’ community groups and some are printed by small presses, while a few are helmed by big publishing houses. And it is through these essential books that we consume our country.

But let us begin at the beginning, going back to the remarkable Time & Talents Cookbook, a (mostly) Parsi cookbook. First published in 1935, it was put together by the Time & Talents Club, peopled mostly by upper class Parsi women (arguably the most Westernized community during British rule). It features not just traditional Parsi recipes such as colmino saas (prawn sauce) but also a fair amount of soufflés and chiffons. Later editions show a further waxing and waning of culinary fashions; fewer snows and soufflés, for one, and the creeping in of microwave recipes.

Similarly, you can make landfall on Rasachandrika, written by Ambabai Samsi and spurred on by a ladies’ association, the Saraswat Mahila Samaj, a community of Maharashtrian ladies founded in 1917 in Mumbai. It was first published in 1943, a time when the British hold over India was eclipsing. The book reveals the entire archaeology of Maharashtrian life; it documents a list of recipes, certainly, but also religious festivals and what to cook on which days, as well as home remedies for common ailments, all practices that built the Maharashtrian community. The book also shows a gentle reconfiguring of personal geographies as an undertow of British dishes seeped in—Aspic eggs, Irish stew, and Apple Charlotte, among others.

Rasachandrika was also published on the cusp of women’s emancipation. In the introduction to the Marathi edition, Ambabai Samsi’s author’s note hints at this timing. “Since formal academic education has now become more widespread than in my time, girls cannot devote much time to cooking until they are about 20,” she wrote. “As a result, it becomes very difficult when they first undertake the responsibility of cooking. Under these circumstances, Saraswat girls can refer to this book and start cooking typically Saraswat dishes without any difficulty.”

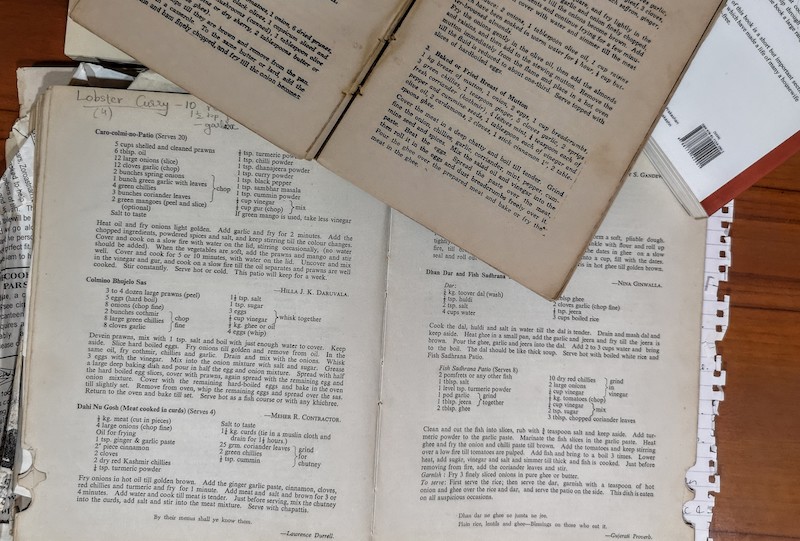

Photo by Meher Mirza

Photo by Meher Mirza

As women’s education surged, and amid the independence movement, more women became prominent figures in public life. Some, such as poet-politician Sarojini Naidu and freedom fighter Bhikaiji Cama, were catapulted to national fame. Yet the voices of those women who ran home and hearth were vanishingly faint. This is where cookbooks came in; they offered the rare opportunity for women to write a part of their lives into a book, while doing so within the boundaries tacitly prescribed by their communities. They had the imprimatur of respectability, offering tendrils of agency to the writers. Cookbooks gave heft to the outlines of an everyday life, outside the sphere of public life.

These books are an ode to memory in a time that hums with generic packaged foods, access to the internet, and popular television shows from around the world—all of which are rapidly contouring modern kitchen life.

Take, for instance, Meenakshi Ammal’s seminal Tamilian vegetarian cookbook, Samaithu Par (“Cook and See”), published in 1951 in three volumes. Ammal was an excellent cook. Goaded by requests for recipes by family and friends, she congealed her kitchen-hardened knowledge into a cookbook. But “back in the late 40s and the early 50s, cookery books were unheard of,” we read on the book’s website. “Many people scoffed at the idea of a best cookery book. But Meenakshi Ammal was not easily dissuaded.”

Just as well, because the immense popularity of its first edition brought a clutch of Hindi, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, and English editions. Ammal tips into it the full weight of her erudition; her penmanship is deft, no-nonsense, and confident. Her work secured South Indian cuisine firmly in kitchens around the country (and later, the world). Samaithu Par is still published by a tiny press, Sabanayagama Printers, in the belly of Chennai city.

Samaithu Par‘s website references its usefulness for both men and women in an age where gender barriers are more fluid than before; in particular, it can be helpful to young students about to embark on their studies abroad. Similarly, the book is also often given as a wedding present to kerflummoxed couples setting up home for the first time.

More recently, in 2010, the Urdu newspaper Inquilab published a rare quartet of recipe books from four Indian Muslim communities (Bohra, Kashmiri, Konkani, and Memon) in both Urdu and English. Similarly, the Zoroastrian Stree Mandal (Ladies Association) of Hyderabad and Secunderabad has launched a new edition of The ZSM Cookbook.

Publishing houses today, usually wary of risk-taking, are now slowly following in the wake of these. Ummi Abdulla chronicled Mappalah cooking in her book Malabar Muslim Cookery in 1981 (Orient Blackswan). The Bong Mom’s massively popular blog of Bengali recipes has now become a cookbook, also known as The Bong Mom’s Cookbook (2013, Collins India). And then there is Husna Rahaman’s Spice Sorcery, a polymorphous fictionalized tale of Kutchi Memon gastronomy into which are pleated several recipes (2014, HarperCollins); the book dims the lines between reality and fantasy.

Even more heartening are Penguin’s recent releases focused on regional cooking—it has brought out an entire line of regional Indian cookbooks such as The Essential North-East Cookbook, The Essential Kerala Cookbook, and The Essential Goa Cookbook.

Photo by Meher Mirza

Photo by Meher Mirza

These are all significant today because, as Appadurai says, “They begin to provide people from one region or place, a systematic glimpse of the culinary traditions of another.” But they are also an ode to memory in a time that hums with generic packaged foods, access to the internet, and popular television shows from around the world—all of which are rapidly contouring modern kitchen life. They act as a Proustian madeleine of sorts, modeling Indian culture for the considerable number of Indians living abroad, who have glazed memories of home cooking. As a consequence, these books have grown into a redoubt of Indian culture, cultural artifacts that stave off the fear of a loss of Indian traditions.

One recent example, Archana Pidathala’s Five Morsels of Love, is a self-published book of Andhra recipes dedicated to her grandmother and thickened with the warmth of her family stories. Her recipes boast a density of detail, explaining terms such as “tempering” that may baffle a novice cook. A curious, kind book about her grandmother, it shot to fame when it was shortlisted for the Art of Eating Prize in 2017 and was subsequently featured in The New York Times, NPR, and elsewhere.

Photo by Meher Mirza

Photo by Meher Mirza

Pidathala confined herself to a small region, a small community, but rather than hobbling her into obscurity, it has energized the world of Indian food publishing. It would be wonderful if readers and publishers took this lesson to heart by publishing more, reading more, and helping to elevate these cookbooks from oblivion to the pillars of national cuisine that they are.

*Parsis are Indian Zoroastrians, followers of the prophet Zoroaster, the world’s first monotheistic religion that originated in Iran.

Meher Mirza

Meher Mirza is a Mumbai-based independent writer and editor, with a focus on food, culture and travel.