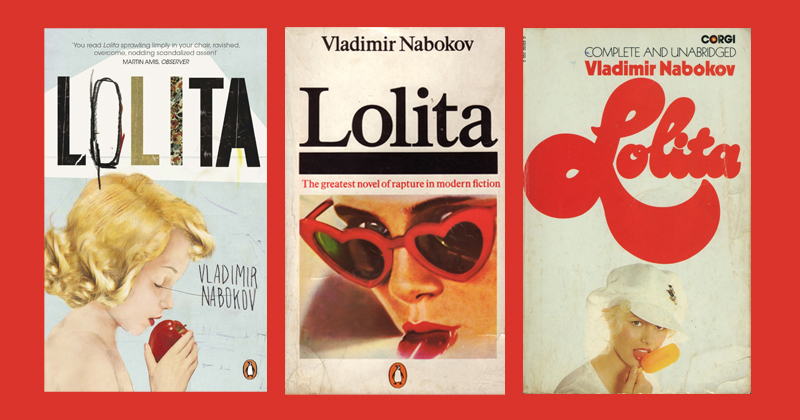

The Pure Pleasure of Reading Lolita‘s First 100 Pages

Hanya Yanagihara on Nabokov's Rich Language

When I was 13, my father gave me a copy of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. Certainly in the way he taught me to read it, Lolita was never a book about a love affair or about pedophilia. I remember how he’d get annoyed when anyone called it a love story—to him, the point of the book was the language, the obvious delight of a nonnative English speaker basically playing with his food. Yes, the Baroque style and invented adjectives convey the creepiness and the unctuousness of the narrator. But they also convey Nabokov’s pure joy of being able to muck around in another language.

That’s what I love about Lolita, too: this overblown-ness, the rich, self-conscious pretension of language. The Americanisms that Humbert encounters, and mocks, and also delights in, juxtaposed against the clear indulgence of English itself. That excess, his way of manipulating words, his way of rolling around in sentences, was in my father’s reading always what this book was about and its true import and genius.

Nabokov, of course, was a famous lepidopterist, and there is that sense in this book of how it feels to dissect a language and understand its innards; at the same time, he’s able to reconfigure words into something else entirely. It may be why I’ve never actually finished the book: The story was never the important part. I’ve gotten to about a third of the way through, right after Charlotte Haze, Lolita’s mother, dies in the car accident. Every couple of years or so, I revisit the first 100 pages—but I’ve never read beyond it.

I hope Lolita would be allowed to stand alone if it were written now, but I could also see how an editor might want it to be more minimalist, more streamlined. And that’s too bad, because literature depends upon writers taking large leaps on the page. Whether it’s plot, or characterization, or structure, or a voice, or the language, a book has to take risks with at least one thing.

Yes, Lolita is not a tidy or inert book. But a tidy and inert book is never going to be worth doing.

A writer has to try to make something new, and what Nabokov makes new in this book is language. In every single sentence, almost, there is something that’s invented, and you can feel it being invented in real time. At the same time, you feel that the writer isn’t looking over his shoulder to see what’s been done before. Nor is he looking into the future to see what the reception might be. It’s that present-tense-ness that a writer must possess, the confidence that what’s being done on the page, in real time, is simply all that is going to matter.

So much of being any kind of artist—whether you’re a composer, or a painter, or a writer— is a lifelong process of trying to forget everything you’ve been taught. When you look at Picasso’s juvenile work, you can see he was a draftsman: He was someone who had been taught how to draw. But he was also, critically, able to unteach himself. It’s the same when you see writers using language in a way it’s not supposed to be used or it hasn’t been used before. What you’re seeing is somebody who has the gift of forgetting (or of selectively ignoring) the rules. Often, this works best when you’ve been taught how you’re supposed to do things—so that, when you’re actually doing your own work, you can unlearn those lessons. But not necessarily. Nabokov is self-taught in a lot of ways, and he writes the way that a very talented autodidact writes.

“It’s that present-tense-ness that a writer must possess, the confidence that what’s being done on the page, in real time, is simply all that is going to matter.”

The best time to write is after your book is bought but before it’s published, because you’re able to write in complete ignorance. You must draw a line between what it means to be a writer and what it means to be an author—an author is a performative role, and a writer is not. It’s so important to be able to forget your public persona when you work. When you’re writing, your responsibility is not to your publishers. It’s not even to your readers. It’s only to the story.

If you can always keep in mind that your only goal is to serve the story—whatever the story may be, and however the story may be told—then that’s all the insurance, all the protection, that you need. It’s a pretty basic piece of advice, and it’s very easy to forget, but I think you can never go wrong with it. Whether it comes down to a language choice or a plot point, if you keep your focus only on serving the narrative itself—not the book, necessarily, but the narrative, the story, the characters—then that’s the very best you can do. You hope that focus emboldens you to make all the right choices for the creation itself, and only the creation.

I say that everything should serve the story. But Lolita is the rare book that successfully breaks that rule. The wonderful thing about this book is that you could take its first 100 pages, tear them out, cut them into bits, and scatter them: And just by picking up any one of those bits, a paragraph, or a sentence, or a line, you could have a singular reading experience. When we talk about books being poetic, what we often mean is that there’s an indulgence or a fuzziness to the language. This is poetry of a different sort. It’s sharp, and it’s unpleasant, and it’s barbed, but it’s also mischievous, and playful, and fanged. It’s language at its most fun, at its most enjoyable, at its most delightful, and also at its most wicked and resonant. I wish more people read the book that way, instead of letting it become eclipsed by the scandals and the conversations that have surrounded it. The pure pleasure of reading Lolita is what makes it as enduring as it is.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Light the Dark: Writers on Creativity, Inspiration, and the Artistic Process, ed. Joe Fassler. Used with permission of Penguin Books. Copyright © 2017 by Hanya Yanagihara.