The Problem with Calling Nature “Wild”

“When you seek wildness, where, precisely, do you go?”

“Wild” is a challenging word.

“Wild” is used to describe a misbehaving child, a kick-ass party, a city with traffic congestion problems, a piece of salmon that hasn’t been designed in a chemical lab, a backyard overgrown with too many weeds. In the same breath, wild is a parcel of land or sea that seems to resist human control.

“Wild”—its etymology tells us—signifies something that is self-willed. Relatedly, “wilderness”—arising from a combination of “wild,” “deor” (deer or beast), and “ness” (promontory or cape)—is a place that abides by nothing but its own will, a nonhuman will. But if things were that simple, we would be remiss in calling “wild” challenging. What makes the word “wild” semantically treacherous is its lack of formal policing.

If you google “wild Galápagos,” National Geographic, the Travel Channel, a 3D IMAX movie come up. They all call the Galápagos “wild.” No surprise there. But so does a company called “Wild Planet Adventures,” which has a vested interest in selling its cruise package. Others do the same. If they want to sell us a well-kept resort town, they call it “wild.” It doesn’t end there. The world is full of places that seem wild on the surface.

Wild Dolomiti is the name of a book promising to reveal the Italian Alps’ most “pristine” trails. “Wild” is a playground in New York City’s Central Park. “Wild Adventures” is a theme park in Georgia, in the United States. “Wild and Natural” is the name of a Cosmetics company that operates on the island of Ibiza, Spain. How can a word be so loose that it can be coupled with anything or anyone? How can it be so generous and so undiscriminating, so cheap and yet still so enticing? Sure, lexical law enforcement is not exactly a thriving business, yet the word “wild” seems more promiscuous than most.

In response to this semantic anarchy, we could establish some clearly demarcated boundaries to protect a true and objective meaning of wild. American legislators attempted to do this when they passed the US Wilderness Act in 1964. For them, “wild” was a land that had a distinctly wild “character”—that is, “untrammelled” land that appeared “to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man substantially unnoticeable;” land that had “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation”; land that was “at least 5,,,, acres” or was “of sufficient size” to make its “preservation” practical; land that contained “ecological, geological, or other features of scientific, educational, scenic, or historical value”; in other words, land that was—though they never did mention it—Indigenous land.

The more we reflect on it, the more “wild” begins to feel not only promiscuous and polysemic but also shallow and arbitrary.

Alternatively, we could choose to do what many governments around the world have done: heed the specifications of the world’s most influential environmental NGO, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (better known as IUCN). In doing so, we could define “wilderness” as “protected areas” that are “usually large unmodified or slightly modified areas which retain their natural character and influence without permanent or significant human habitation and which are protected and managed so as to preserve their natural condition.”

Problem solved, right? Well, only if we are willing to ignore that these two definitions offer no clarity whatsoever on their most important qualifiers. Who determines whether a place is truly unmodified, only slightly modified, or sufficiently modified? What is a “natural character”? When is human habitation “significant”? Above what threshold is the impact of humankind “substantially noticeable”? What constitutes “primitive” recreation? And who has the power to consider something recreational? Hunters? Landscape photographers? Ski resort developers? Hikers? Does a place have to be protected to be considered a true wilderness? If so, isn’t the very management that ensures protection a violation of a place’s natural (i.e., nonhuman) character? How can something be wild when it has fences around it and surveillance cameras installed at its gates? Above all, whose opinion and perspectives on all this counts?

Things get even worse if we go deeper. More than challenging, the idea behind “wild” can be downright dangerous if you consider that to preserve their natural character—so valuable from a human-defined ecological, geological, historical, educational, or scenic point of view—wild places must be protected from human interference. This ideology has historically been the perfect justification for eviction and resettlement programs that have displaced thousands of residents, turning Indigenous people into conservation refugees.

When used superficially, “wild” is purely rhetorical. It’s the Hollywood “wild” of Chris McCandless, played by Emile Hirsch, venturing into the Alaskan bush in Into the Wild. It’s the “wild” of Reese Witherspoon retracing the steps of Cheryl Strayed along the Pacific Crest Trail. It’s the “wild,” youthful imagination of Call of the Wildand Where the Wild Things Are. It’s the lawless “wild, wild, West” and the people-less landscapes of “Wild Africa” or India or Antarctica or whatever continent the BBC flies to tonight. It’s the pseudo-reality of Man vs. Wild and Out of the Wild: The Alaska Experience or whatever reality show the Discovery Channel produced last week.

Used politically, “wild” can be divisive, militant. It’s the “wild” of fortress-style conservation schemes around the world, schemes that end up separating people from their land in the name of tearing culture from nature. It’s the “wild” of first-class ecotourism, which puts an economic premium on luxury ecolodges and turns third-world residents into guides, cooks, dishwashers, and maids. It’s the short-sighted “wild” of neat borderlines and environmental zoning, which permits only trail maintenance on one side of a fence and slash-and-burn logging on the other.

The more we reflect on it, the more “wild” begins to feel not only promiscuous and polysemic but also shallow and arbitrary. It’s a vacuous brand. Exchanged like cash, “wild” is a dirty, anonymous, and spiritless currency that has more value here, less there. In this capitalist environment, remote fishing and hunting lodges, green eco-resorts, guided paddling adventures, and entire countries are marketed and sold in the name of wild.

We are not the first to notice this. Throughout modern and contemporary history, wild, wildness, and wilderness have fed the book-publishing industry as much as they have the business of TV and film production. From Thoreau and Goethe to Snyder and Turner, from Strayed and Bryson to Macfarlane and Griffiths, scores of writers before us have answered the call of the wild from places wild in their minds and their hearts. But “wild” continues to evade cognitive capture; its affective notional slipperiness mimics its remarkable semantic agility.

The idea of wild is elusive, but so, too, are its geographical referents. When you seek wildness, where, precisely, do you go? Logically, to a place where you expect to find it, to a place that you deem wild. That is what most writers and adventurers do. But when you do, a problem emerges. If you look for wildness where you expect to find it, what you see mirrors your mental images. Wild places become a mere test of your ideologies, a manifestation of your fantasies, aspirations, and fears. Wilderness areas become fantasies of well-cultivated minds and well-trained bodies keen on putting their Instagram flag on the next highest peak.

__________________________________

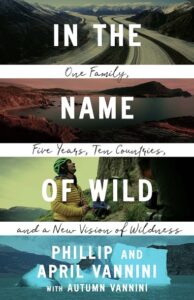

Excerpted with permission from In the Name of Wild: One Family, Five Years, Ten Countries, and a New Vision of Wildness by Phillip Vannini and April Vannini, with Autumn Vannini, 2022, On Point Press, an imprint of UBC Press, Vancouver and Toronto, Canada. For more information go to www.ubcpress.ca.

Phillip Vannini and April Vannini

Phillip Vannini and April Vannini are ethnographers and filmmakers. They share an interest in exploring the meaning of “wild” and “wilderness” and are the authors of Wilderness and Inhabited: Wildness and the Vitality of the Land and the directors of In the Name of Wild and Inhabited. They teach in the School of Communication and Culture at Royal Road University and live on Gabriola Island in British Columbia.