The Power of Giving Your Disabled Characters a Happily-Ever-After

Sabina Nordqvist on Writing a Romance Novel that Decenters the Abled Gaze

The day I limped into a seven-month chronic pain rehab program, the first thing they told me was: we don’t talk about pain here. We were not allowed to exhibit “pain behaviors” either, which were physical responses that would alert others to our pain, like wincing or groaning. The therapists said people were uncomfortable with pain and wouldn’t want to be around us if we made them aware of it.

This was a grueling full-day program that required a three-times per week commitment at a clinic an hour and a half away. It consisted of various physical and mental therapies, as well as biweekly meetings with a team of pain specialists. I had already been diagnosed with a rare neurological condition called idiopathic intracranial hypertension, but the reason I could no longer walk without excruciating pain eluded all the specialists I consulted.

When one of those doctors prescribed the rehab program, I couldn’t afford it. The prolonged absence also exceeded FMLA allowances and might make me lose my job. The doctor said losing my job was “better than ending up in a wheelchair for the rest of my life.” And since no one would take my pain seriously, I agreed to go even though it meant taking out a second insurance and going into debt.

I expected to get help. Surely all these medical professionals working together could solve the mystery case of my pain. Instead, I found myself trapped in a system that insisted I could fix myself if I just stayed positive and tried harder.

So I pushed through the pain. I did guided imagery and deep breathing while imagining myself on a beach with soft waves rolling in the background. I did physical, occupational, and aquatic therapy. I listened to nothing but the 80s music that played for eight hours a day since we weren’t allowed to have phones or devices to make the time pass more quickly. I did biofeedback and endured countless sessions of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

I continue to include more than one disabled character because I know what it’s like to be in isolation—and how it feels to finally be in community with those who understand.

If we did talk about pain or—God forbid—cry because an exercise hurt, we were singled out and forced to do more CBT. CBT was used to deny pain medication and dismiss reports of worsening symptoms. It framed suffering as a “thinking problem” rather than a medical and systemic one because it ignored the realities of pain, poverty, medical gaslighting, and the massive barriers to getting a diagnosis.

Day in and day out, we were taught that it was all in our heads.

We were not even allowed to talk about our pain with our cohort. This was something I had looked forward to when I started rehab—the ability to connect with other disabled people who understood my experience. Instead, we had brief clandestine conversations in the locker room at the end of the day.

Most of the group went to the cafeteria together for lunch, but I couldn’t join because it was in a different building, and I couldn’t walk that far. I desperately wanted to use a wheelchair to be included, or at minimum, a cane, but mobility aids weren’t allowed. Not only would it be “a signal” that we were “giving up,” but we were required to ambulate independently in order to stay in the program.

I sat by myself on a bench in the locker room to eat every day until the psychologist told me I wasn’t allowed to “isolate myself.” It was strange to think we were meant to socialize—but only if it didn’t include talk of our health.

We had group therapy, but it only consisted of lectures and presentations from the psychologist. We learned about traumatizing studies in which rats were electrocuted until they gave up trying to escape electrocution and just lay there—an outcome that “proved” that people like me stopped trying to get better if we accepted our pain.

“Your brain will change,” he warned us. “It’ll misfire pain signals.”

My brain did change. But not in the way that he said.

I began to internalize what they told us, believing that maybe, just maybe, it actually was my fault. Maybe I wasn’t trying hard enough. Even though every exercise I did made me worse, there was always a voice in the back of my head that said, this program wouldn’t exist if it didn’t help anyone, right?

I continued to deteriorate. I remember calling my family doctor in tears at a work conference in New Orleans because I couldn’t make it down the hallways of the conference center where I was supposed to present while standing up. I left dinner with colleagues because the pain was so extreme, I almost blacked out at the table. But there was never an offer of pain medication; only antidepressant after antidepressant, despite no diagnosis of depression.

When that didn’t work, I got nerve medication. But that made me gain weight, and gaining weight when you have mystery pain is the last thing that will help you get a diagnosis.

Without anyone to validate what I was going through, I started writing about it to process. After rehab, I would write for three hours while I waited for my partner to finish work and come pick me up.

At the time, I was mostly engaging with disability representation through fanfiction. When I first got sick—a year before rehab—I latched onto popular novels that featured disability and clung to them as a way to work out my grief. It was also a way to dissociate. I gave the disabled characters swoony romances and happy endings alongside their pain.

But I wasn’t having any meaningful interrogation of what stories I was consuming and why; I was simply desperate for any kind of representation where disabled characters didn’t die.

As my seven months in rehab crawled by, I started noticing that a lot of the stories I had once been excited about were not actually that nuanced. They were full of holes and inaccuracies, and sometimes, the representation was downright harmful. It turned out most stories about disability were written by authors who weren’t disabled, so they centered an abled gaze.

My experience—the one where you aren’t believed, where you become homebound and lose your job and your friends because of disability—wasn’t represented outside of memoir.

I couldn’t find the book I needed, so I wrote it myself in those fatigued hours after rehab: an original romance novel that centered chronic pain and a program like mine. It had a sexy, forbidden romance, rehab drama, the search for a diagnosis, and social commentary on medical gaslighting and ableism in the US healthcare system.

With a guaranteed happily-ever-after, romance allowed me to explore these topics safely. I could write stories that celebrated our bodies even if they hurt. Where people like me were allowed to show up as our full selves and didn’t have to shrink for someone else’s comfort.

Novels often treat illness as an ending—of desire, of intimacy, of narrative momentum—but in the romance genre, I could offer a counterargument where disabled people got to have love and happiness without needing to be cured. Writing romance became a way for me to imagine love that wasn’t contingent on wellness.

After rehab ended—and I got worse and lost my job, with no diagnosis in sight—doctors continued to find any excuse to dismiss my pain. Instead of offering me treatment or medication, one pain management doctor even said, “Have you considered getting divorced? Sometimes the pain stems from a bad relationship.” I was a newlywed.

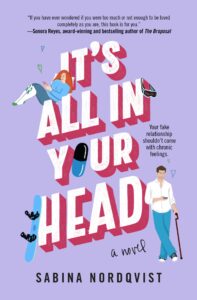

With each new symptom, I channeled my thoughts into rewriting my rehab novel and other novels that also featured characters with chronic pain, including my debut, It’s All In Your Head. After great feedback from disabled and chronically ill critique partners, I thought my novels would fit into an underrepresented corner of the market.

But I quickly learned that the traditional publishing world, in a lot of ways, mirrored my experience at rehab. Many agents and editors, it turned out, did not think people would want to read about characters who had chronic pain.

I was told that they couldn’t “connect” or “relate” to my disabled characters. For that matter, why did I need to have two disabled leads anyway, when it would be better to have a disabled woman and a love interest who was a caretaker? There were too many medical appointments; could we cut some of those? Why couldn’t the characters get diagnoses more quickly? There wasn’t enough “hope” in my stories. These themes were “too heavy.” Or as an editor once pointed out: could the doctors please be nicer to the patients?

At first, I was baffled: twenty-five percent of the population had a disability. How could we read about war, loss, cheating, and infertility, but chronic pain was the topic that was too heavy?

As I met more disabled writers, I realized the lack of nuanced representation wasn’t because no one was writing it. They were getting the same feedback. Disability could be published, but it needed to be palatable. The versions we were writing made readers grapple with the realities of being disabled in the United States.

My rejections only made me more determined to keep centering disabled people’s experiences. I came to realize that there was some truth in what I learned at rehab. People, in general, were uncomfortable with lasting pain.

I saw this mirrored in my life and the lives of so many of my friends who became chronically ill or disabled as adults. At first, friends show up with casserole dishes and themed care packages. But as you continue to remain disabled, the phone calls become fewer and farther between. The expectation becomes that you either get better or stop talking about it entirely. I also see it when I use a mobility aid and people tell me in parking lots and grocery stores that I’m too young to be disabled or that they’d rather be dead than “stuck in a wheelchair”—when in reality, using a wheelchair finally allows me to participate in activities that I was previously excluded from.

More than a decade after rehab, I am the nightmare outcome for the program: I am more disabled than before, I joyfully use mobility aids when I need them, and I talk about my pain as much as I want. I think it’s more important than ever that disabled people get to see their experience represented on the page by other disabled people. I still write romance because it allows me to center care, humor, and desire in bodies that are so often denied them, and to say, without apology, that we are worthy of these stories too. I continue to include more than one disabled character because I know what it’s like to be in isolation—and how it feels to finally be in community with those who understand.

Disability representation in romance has also improved somewhat. I can now find romance novels featuring disabled characters written by authors who have those disabilities. However, discussions about disability representation in publishing are still largely confined to the disability community, rather than being treated as a broader industry concern—mirroring the cultural discomfort with acknowledging disability beyond moments of abstraction or inspiration.

My hope for It’s All In Your Head is that it will allow people to have more honest conversations about pain. I hope someone will feel a little less alone and a lot more seen. I know now that there are people out there who want to read about our full lives, not just the palatable version.

Romance, joy, and connection are not out of reach simply because we are ill or disabled. Because love, in the end, makes space for pain too.

__________________________________________

It’s All in Your Head by Sabina Nordqvist is available via Grand Central Publishing.