There is no greater compliment in this world than being the uncooperative catalyst of another person’s misery, if not all-out self-destruction. The critical word here is uncooperative. It is easy, lazy, and dishonorable to deliberately distress another human being. But to do so unintentionally, or better yet, unwillingly—for one’s mere presence to cause another pain, not by any act of violence, but by the force of the bottomless pool that is unrequited love, that pool that both draws and prevents the other from moving closer—to be loved and not to love back: this is the definition of power.

It’s a state of affairs that most privileged, well-educated, self-involved people take great pains to shape in their favor. In the truest mark of artistic mastery, C. Wesley Range IV made it seem effortless.

So highly attractive to women was Wes that, at first glance, for the many (many) girls he had disappointed, it might have been tempting to paint a twenty-first-century Rick Von Sloneker—tall, rich, good-looking, stupid, dishonest, conceited, a bully, a liar, a drunk and a thief, an egomaniac, and probably psychotic. In reality, he was only about half of these things, and if Wes was a bit of a devil, he was the kind with whom you’d sympathize. At nearly thirty, Wes was still boyishly handsome, with an Ivy League aesthetic perforating his hipster urbanism, and (85 percent of) a Henley-winning physique. He was kind to children, respectful of the elderly, and attentive to dogs. He rarely drank alcohol, precisely because he knew he had the tendency to overdo it. The lies he told were generally engineered to spare hard feelings, and the main recipient of such lies was himself. With the recent tidy valuation of his tech startup, Ecco, one might have predicted an uptick in ego, but his oldest friends would insist there’d been no change. New acquaintances would scoff that he came from money anyway, until they learned the sorry state of his trust, at which point even Zuccotti Park–populist skeptics had been known to forgive him the suffix and develop a crush. Upon closer inspection, they found Wes could almost pass for self-made—if anything, he spent too much time at work. Factoring in his polite yet straightforward general manner, discretion in sexual encouragement and discouragement, discernment in those choices, and, most especially, his unwavering commitment to (albeit serial) monogamy, it was impossible to brand Wes a womanizer, let alone a rake.

It was a formidable talent, making women feel valued and respected. It shouldn’t have been, but it was. Rarely making the first move, even less often a promise, Wes’s quiet self-assurance and Sadie Hawkins approach tended to attract the kind of women to whom Wes was most attracted: independently minded and forward thinking enough to proposition a man, confident enough in their own desirability for that man to be him. His real specialty, though, was breakups. Wes’s ready willingness to have an uncomfortable thirty-, maybe sixty-minute conversation and be cleanly, respectably done with things starkly broke ranks with long-established practice in male-to-female relationship termination theory. If the great lengths and dramatic unpleasantness his friends accepted to avoid such encounters boggled Wes’s mind, his own compassion and transparency shocked the hell out of them. But to Wes, empathetic, definitive communication was a kind of secular Pascal’s wager, one of those rare pragmatisms with the added benefit of humanistic appearance. In the absence of ugly breakup mechanics, most women ostensibly bore their post-Wes devastation in ironic nostalgia, if not pride of conquest. Those who did resort to the darker comforts of fiction were hardly believed anyway. Such was the sterling reputation of Charles Wesley Range IV: indelible to the point of immunity, even, on occasion, from the truth.

As the founder and CEO of a company that pinpointed needling errors in vast haystacks of code, Wes would have been the first to admit that with any sufficiently large data set, there are outliers. And as is often the case with outliers, the two women who defied the customary pattern of Rangeian relationship dynamics had a disproportionately large effect. You had to go pretty far back to find the first black swan, a taciturn brunette from—where else—prep school, an upper former two years his senior. It had been an admiration from afar: the obsessive, worshippy sort of lust-love that can only flourish from a distance, but, from a distance, self-perpetuates. Why had he been unable to approach her? Based on the way she’d looked at him a few times, he thought maybe she would approach him. But she never did, and there were always other girls more forwardly demanding of his attentions. Before he knew it, she’d graduated and was gone. Their missed connection was the rare kind of adolescent regret that, with time and maturity, became more rather than less painful. She was now, in his mind, far more than a person. She had come to represent every decision he hadn’t made, every opportunity forgone. She was regret personified. One can get over bad decisions, lovers lost. But it is impossibleto get over someone you never really had.

The second outlier was just downstairs, the damn incendiary making all that racket: the catalyst of his misery, the love of his life, Diana Whalen. Wes’s wife.

__________________________________

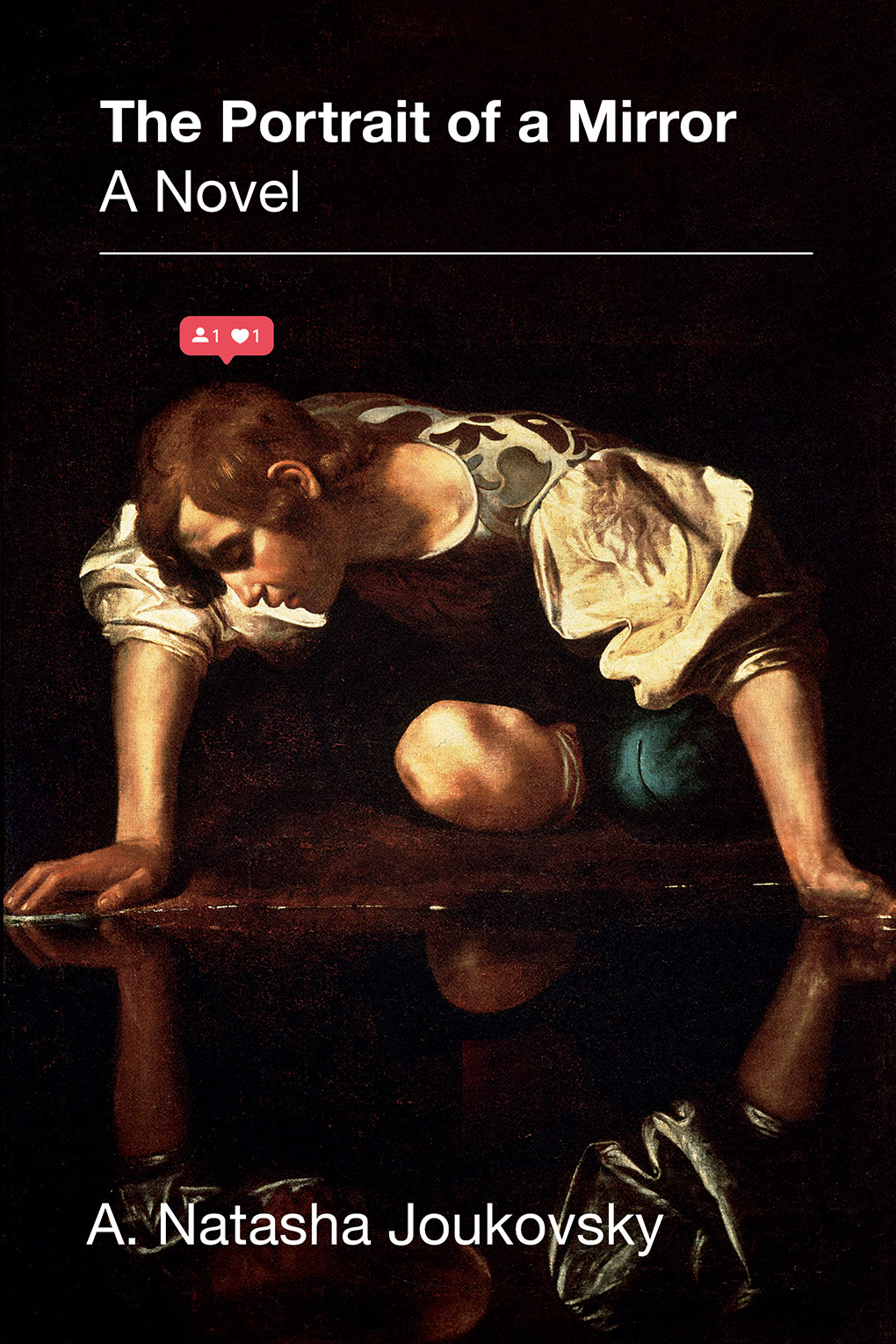

Excerpted from The Portrait of a Mirror by A. Natasha Joukovsky, with permission of publisher The Overlook Press © 2021.