The Political and Narrative War for the Iranian Dead

Poupeh Missaghi on a Decade of Protest and Censorship

In a video that plays on repeat, I see blood on the floor and the legs of a man who is asking for water. In a video that plays on repeat, I see students pushed to a corner, like slabs of meat, as guards scream over them. In a video that plays on repeat, I see a woman’s body carried from a car to be taken into a hospital.

My investment in watching videos of violence done to bodies in the aftermath of the disputed 2009 Iranian presidential election and documenting lost lives began while writing my novel trans(re)lating house one. Contentious debates and pre-election tension, as well as irregularities pointing to widespread electoral fraud, led people to the streets shouting slogans like “Where is my vote?” The situation was exacerbated by lack of proper official response, and the peaceful protests of the Green Movement were soon met with violence and arrests.

The events drastically affected both my psychological state—I had been one of the people protesting on the streets—and my choices as a writer. My consequent research led to my discovery of how government officials were responding to and representing the dead of that movement.

In November 2019, when one of the largest public protests since 2009 broke out following a sudden rise in fuel prices, once again the official response was nothing but violence. This time, however, it was much more severe. This still came as a shock to me.

Even though the dead body has always been a site of contestation under the Islamic regime of Iran, 2009 had shifted the balance of power. Now, people had phones and their phones had cameras. Citizens had become journalists. The silence and secrecy around many of the previous incidents, which only meant that details of the deaths seeped into tight-knit circles, had disappeared. These narratives were fast becoming part of the public discourse.

It wasn’t enough for the ruling power to eliminate the bodies of living protestors; confiscating their narratives was just as urgent. Families were warned not to speak out. Funerals were held under strict security. The word “martyr” was once again brought to the center of the conflict between opposing forces. In cases where people called those killed by the government “martyrs,” the government would do what it could to silence such narratives by using state media, for example, or shattering the tombstones of the dead. In other cases, the government would identify individuals killed by their own forces “martyrs,” creating the false narrative that they were murdered by enemies of the state.

During the most recent events, I was here on the other side of the world and followed updates online that indicated a brutal crackdown. Unlike a decade earlier, coverage of the unrest spread fast across various platforms. After the first day, however, everything went silent. The internet was shut down by the Iranian government. The disappearance of all those virtual bodies who were reporting, discussing, or protesting on Twitter, Telegram, and elsewhere created a terrifying void. I felt an acute sense of loss, as if a loved one had died. And it wasn’t just me; many Iranians in the diaspora were feeling the same heaviness. What was once a vague sense of exile had suddenly become concrete.

Shutting down the internet gave the government freedom to unleash its powers both on protestors and on stories about what was happening. For an entire week, hardly any news came out of the country. Then, a few tweets and videos began appearing, and eventually a clearer picture of the violence emerged. I read a tweet about the town of Mahshar in southern Iran, which said the area had become a “slaughterhouse.” I couldn’t stop thinking about Etel Adnan’s last line from “To Be in a Time of War”: “To look at the narrow and long road that leads the world to the slaughterhouse.”

A New York Times article about the same incident used the word “carnage” in its headline. The video of that attack and all the others from around the country showed a level of chaos and brutality I hadn’t seen even in the ones from 2009. The sound of bullets reminded me of a war zone. On those November days when our virtual bodies, both inside and outside Iran, were held captive, between 300 and 1500 people were killed. With the exact numbers unknown and many families afraid to voice their loss and demand accountability, the silence around these deaths continues to feel heavy.

Still grappling with the void of November, Iranians found themselves in another turmoil following the US assassination of Iran’s Major General Suleimani in Iraq and the threats of war. But the blow that shattered our souls came from an unexpected direction: The Iranian missile that struck Ukrainian Airlines Flight 752, killing 176 passengers, mostly Iranians, and the crew. Iranian officials and media hid the truth for days, and it was only after evidence leaked that they confessed.

Another war of narratives started, and there is no real hope for any truthful official reports or for justice to be served. The discrepancy between the national funeral processions held for Major General Suleimani and the tumultuous, restricted funerals held for victims of the plane crash, along with their media coverage, reveal much about a propaganda machine set loose once again.

Susan Sontag, in Regarding the Pain of Others, describes the impact of an overabundance of images and information on our sense of moral responsibility and the ever-growing risk of desensitization in the face of brutality. As our reactions, or lack thereof, to the state of the world can attest, this is surely true to some extent. It is because we watch and read mainly for information and analysis, skipping from one news source to the next to make sure we’ve covered it all.

But when I started to read and reread and watch and rewatch the same raw material over and over again for my research, I realized that at some point the affect became more important than the data. Staying with the material makes it more palpable, not just in your head but in your body too. There is always one picture, one video, one voice, one sentence, one detail that can break you.

A mother clings to the bars, wailing to be allowed to bury her beloved child, while a woman from inside reaches out to hold and caress her.Of all the heartbreaking information resurfacing about the plane crash, it was a short video from one of the victims’ funerals in Iran that brought me to my knees. Rusted scaffolding stands around a hole, piles of dirt stacked next to it. The hole is about to become a grave holding what is left of a body. Inside the cordoned area stand several men in uniform, along with women covered from head to toe in black veils, both groups tall, silent, and official.

On the other side of the iron bars, there is a distressed crowd. A mother clings to the bars, wailing to be allowed to bury her beloved child, while a woman from inside reaches out to hold and caress her, telling the mother she has every right to be devastated, asking her what she can do for her. The mother responds, “Don’t do anything, just leave us alone,” barely holding herself up, asking the woman not to touch her, moving away from her and the bar, letting go in the arms of another mourner.

I watch the video and am more enraged by this gesture of kindness, fake or real, than by the images of the brutal attacks of the past month, sensing a growing desire for revenge. I watch the video and wonder, like many others, how can the woman hear those cries, watch those scenes, go on with daily life, and continue to do what they do.

But then I refer back to what Hannah Arendt said about how, at a certain point, a person who is complicit in a totalitarian system “fears leaving the movement more than he fears the consequences of his complicity in illegal actions, and feels more secure as a member than as an opponent.” In the past few months, her microscopic dissection of tyranny has been a compass for me in an increasingly unnavigable world.

In trans(re)lating house one, I raise many questions about our relationship to the dead and their role in defining our (hi)stories and lives. As my characters follow a trail of statues and bodies missing from Tehran, they wonder, “Why does telling the stories of the bodies, missing or buried, seem to be the next best thing for survivors who have not been able to reclaim the bodies of their loved ones?” “Can the living even have a narrative without narratives of the dead?” “Why should we tell the story of the dead?” These questions were mainly asked in relation to the events of 2009, but as the book comes into the world, they are being recontextualized under the weight of the recent tragedies.

No one can ignore the power of our minds and words in giving testimony about our past and reshaping our present and future. But in the end, we are all creatures with bodies; it is only through and in our bodies, whether living or dead, that we have a voice to narrate what has befallen us. Any injustice to the body is an injustice against our humanity, robbing us of our most important human right: that of life, that of breath.

__________________________________

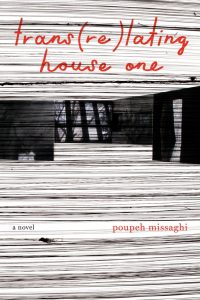

Poupeh Missaghi’s novel trans(re)lating house one is available now from Coffee House Press.