Race and Spectacle in the Circuses of Gilded Age America

Jacob Dorman on Circus Orientalism and Racial Othering

The contemporary circus originated with exhibitions of trick horse riding in 1760s England, and the centrifugal force needed to keep a standing rider on the back of a cantering horse determined the dimensions of the circus ring. The growth and spread of the circus, like the spread of freemasonry, was coterminous with both the Enlightenment and the spread of European empires into Asian, Muslim, and African lands. Riders on horseback raced around the circus ring, sometimes pantomiming patriotic scenes from cavalry battles, as wars, revolutions, and real cavalry charges circled and transformed the globe.

The equestrian circus spread to France by 1772 and John Bill Ricketts began the first American circus with horses and clowning in Philadelphia in 1792, where it found favor with President George Washington, himself an avid horseman. That was also the year that the French Revolution spawned several decades of wars around the globe between France, Britain, Austro-Hungary, and Russia, contributing to the decline of the Spanish and Portuguese empires, the rise of the Russian and British empires, the Haitian Revolution of 1791–1804, the Simon Bolivar–inspired Latin American revolutions of 1808 to 1826, and the unification of the countries of Italy in 1861 and Germany in 1871.

The circus’s equestrian art form came to harness the exponentially greater power of the iron horses that pulled ever-increasing amounts of cargo across the country’s growing network of railroad tracks. There were unsatisfactory experiments with circus travel by rail beginning in 1856, but railroad circuses only took off with the cessation of the Civil War and the standardization and exponential growth of railroad tracks that followed. In America, the golden age of the circus from 1871 to 1915 was facilitated not only by the consolidation and growth of the US nation-state, but also (as with the nation itself) by the power of railroads, which the circus harnessed to multiply its size, grandeur, and geographical reach.

Orientalist depictions of Asian and Muslim subjects featured prominently in the circus parades that wound their way through American cities and towns when the first traveling tented circuses appeared, as early as 1825. In the decades that followed, circus parades with richly ornamented and carved wagons dazzled Americans, announcing the arrival of the tented spectacles.

In 1848, one of the very first accounts of an American circus parade noted that Il Signor Germani, “the great rider of Italy,” would appear “representing the Hindoo Miracles of an East India juggler, attired in the exact costume and caste of his tribe, with an Orrerry [sic] of Golden Globes and Sacred Daggers, the Sacred Vase of Destiny and Fated Bullet. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, typical circus parades included an “Asia Wagon,” with carved representations of Asian peoples on its sides, and sometimes an “Africa Wagon,” which included representations of North African Arabs along with those of sub-Saharan Africans, helping to construct a continental image of Africa in the minds of all Americans that comingled Muslim and non-Muslim African peoples.

Across America, in small towns and large cities alike, the American circus provided a constant and colorful stream of images of human otherness. In addition to representations of the United States, Russia, and Great Britain, a typical Barnum & Bailey Circus parade from 1916 included a cage with four horses and six “Orientals,” a “Tableaux India,” and five Arab boys in their “own wardrobe” riding horses.

Few things could have seemed more exotic or more exciting in Gilded Age America than visions of multihued, brightly colored, bedecked and bedazzled, alluring and forbidden “Moorish,” “Bedouin,” “Persian,” “Arab,” “Indian,” or “Egyptian” wonders, from exotic animals to fierce Bedouin warriors and seductive, veiled harem beauties. The tales of the Arabian Nights featured prominently in these depictions: the Sells Brothers Circus later combined with the Hagenbeck-Wallace and 4-Paw circuses and put together a show called “The Pageant of Persia: The Glorious Origins of the Arabian Nights,” whose poster featured a white-bearded ruler surrounded by a comely courtesan and a wild menagerie of colorfully attired attendants and animals. This image was the source for a later image on the poster of the Al. G. Barnes Circus, called “Persia and the Pageant of Peking,” which then made the leap around 1916 to the Barnum & Bailey Circus as “Persia, or the Pageants of the Thousand and One Nights: The Most Gorgeous Oriental Display Ever Seen in Any Land Since the World Began.”

Later—perhaps when this show had worn thin—the Barnum & Bailey Circus featured five different posters of the “Supreme Pageant of Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp,” which was always depicted along with images of Chinese processions, illustrating the mixed-up quality of American Orientalism and its willingness to fuse the Near and Far Easts.

Exotic animals were even more prevalent than exotic humans in the circus. In the golden age of the circus almost every show had both camels and dromedaries; in 1875 the European Circus had advertised an “Oriental Music Car Drawn by Egyptian Camels” with a picture of a dozen musicians in turbans towed by a team of a dozen camels wearing blankets covered in Islamic stars and crescent moons. In the early 20th century the Ringling Bros. had a “Camel Corps,” with a team of 16 camels pulling an Egypt float decorated with Sphinxes and dark-skinned people in front of pyramids; the Forepaugh-Sells Circus had a similar Egypt wagon pulled by eight camels in 1911.

African Americans were a sought-after audience for traveling tented shows.Occasionally the circus veered into the realm of the scientific, such as the time in 1895 when Barnum & Bailey’s Greatest Show on Earth staged the “Great Ethnological Congress,” which displayed humans representing exotic cultures next to cages of exotic animals in the “Spacious and Colossal Menagerie Tent.” The circus freak show, with its fat ladies and fleshless men, its giants, midgets, piebald “Negroes,” and Siamese twins, had always capitalized on human morphological differences, just as its exotic animals were kinds of animal freaks: the massive lions, the long-necked giraffes, and the humpbacked camels gained their appeal partly from their freakish deviation from domesticated beasts of burden familiar to Americans in both urban and rural settings.

Barnum & Bailey’s Ethnological Congress incorporated the new label of “ethnology” into a longer history of freak show spectacles, in the context of a world that was being thoroughly colonized by European powers. One might even argue that by exhibiting people representing imperial possessions, the circus helped to normalize colonization for Americans and Europeans alike.

The circus was a quintessentially populist art form, and it found audiences among all sectors, races, genders, and classes in 19th- and early 20th-century America. Even before the intensification of Jim Crow in the 1890s, Black audiences frequently sat in segregated seating areas, but there is also evidence that segregation was sometimes enforced less rigidly in the slightly disreputable setting of the circus tent. “Everybody went—all classes, ages, colors and conditions,” wrote Hiram Fuller in 1858, describing a circus in Newport, Rhode Island. “There were as many as five thousand people there, all mixed up with the most democratic indiscrimination—Fifth Avenue belles sitting on narrow boards . . . alongside of Irish chambermaids and colored people of all sizes and sexes.” Many Southern states passed Jim Crow statutes mandating segregation at the circus relatively late, not until the middle of the 20th century’s second decade.

African Americans were a sought-after audience for traveling tented shows. Traveling circuses tended to follow the harvest cycle throughout rural America, when field hands would have had a little bit of money to spend on leisure, and no place had a greater density of circuses and traveling minstrel shows than Mississippi during the cotton harvest. In the words of a performer with the Silas Green minstrel company, Mississippi “isn’t a large state, but it’s one of your greatest cotton states and has a great Race population of real show-going people.”

During harvesttime in 1925, Mississippi boasted an astounding convergence of seven Black minstrel shows, one white minstrel show, and two major circuses, the Sparks Brothers and the Ringling Bros. Barnum & Bailey Circus. In other words, the circus’s version of Orientalist spectacle and Arabian delights undoubtedly reached Americans of all genders, races, and classes, including “race” men and women.

Noble Drew Ali was not the only one who created African identities for “Afro-Americans.” The circus was in the business of exhibiting and commercially exploiting human difference, with a healthy dose of humbug and little regard for ethnological accuracy. In so doing, it provided venues in which “Afro-Americans” could make a living by impersonating Africans—performing and commodifying racial difference. In the 1890s at least four performers claimed to be Africans or African princes—two of whom were circus performers, one of whom was a lecturer, and another of whom was a singer and musician.

For example, a man calling himself “Jave Tip O’Tip, the Zulu Prince” appeared in Yazoo City, Mississippi, in September of 1891, claiming to be a “native African of the fearless Zulu tribe” trying to raise money to help assist three sisters attending school in Washington, DC. The following month he turned up in St. Louis, and gave his name as “Jave Tip-O-Tip, Victoria Flosse, Zulu, Dungan Omish, son of King Cetowa Totowa,” although he also answered to the more prosaic alias of Mr. Dempsey Powers. He sang the well-known Gospel hymn “Come to Jesus” with improvised “African” words.

Tip-O-Tip’s story shows that performances of African-ness in the circus could cross over into lecture and performance circuits in Black churches and colleges.Only a week later, however, the Kansas City American Citizen reported that the Zulu prince was a “first class fraud” and a South Carolinian who “learned of Africa from a showman.” The Race Problem paper of St. Louis reported that Tip-O-Tip had been employed by P. T. Barnum’s circus to play a “Zulu youth,” and that “so well did he learn his part that he concluded he was ‘ just from Africa’ sure enough.” Despite the paper’s assertion that he knew “no more about African customs and habits than an unlettered rustic does about Blackstone’s Commentaries,” Tip-O-Tip enrolled in Central Tennessee State College in Nashville, and gave a lecture as a visiting speaker in July of 1892 on “the habits and customs of his people.” But according to the Detroit Plaindealer, things truly fell apart for the erstwhile African the following month when he was exposed in Covington, Kentucky, and accused of being “a scurrilous thief, robber, and assassin.”

Another man, claiming to be “the real Zulu chief, Mata Mon Zaro,” accused Tip-O-Tip of being “an Arabian, assuming the nationality of an African.” “Zaro” was convinced that his rival’s performances had thwarted his own success as a lecturer, and said “were he to meet him again on his route, he would smack him so that he would feel and know the Zulu’s power.” As Zaro’s accusations indicate, there was money to be made on the lecture circuit by performing as an African, and Tip-O-Tip’s story shows that performances of African-ness in the circus could cross over into lecture and performance circuits in Black churches and colleges.

The most successful “African” circus performer may have been Prince Oskazuma, who was referred to as “the well-known copper-colored African” and “the African prince and warrior.” He toured with the Sells and Renfrow Circus in 1893, then retired to join a company of singers, and by the turn of the century had joined up with Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show, where he was billed as an “African Warrior, Lecturer, Mimic, Fire Fiend.”

Another alleged Zulu illustrates how intertwined these performances of Africanity were with circus performances. Orlando Gibson, who went by the name Boneo Moskego and sang hymns in an “African language,” also performed various feats of strength and courage, such as walking on broken glass, putting a rope in his mouth and defying the strongest men in the audience to pull it out, lifting a man with his teeth, and putting a glass of water in his hand and defying six of the strongest men in the house to prevent him from drinking. Gibson’s performance combined elements associated with various racial groups who met under the circus big top: singing like that associated with “colored” minstrels, walking on glass like Islamic “Hindoo” fakirs, and feats of strength associated with circus strongmen of all nationalities, feats that Walter Brister would also perform to establish his preternatural abilities when he presented himself as Noble Drew Ali, the Muslim prophet.

In addition to “African princes,” which satiated a certain fascination with royalty and nobility among “savage” and Oriental peoples, Barnum & Bailey’s circus also featured degrading images of Africans, such as “a tribe of savages from the wilds of Darkest Africa,” and the famous “Zip,” representing the “missing link” between apes and humans. Barnum had displayed a Black person as a “missing link” called the “What Is It?” as early as 1860, thereby profiting from the social Darwinist idea that people of recent African descent were less evolved than Europeans and that a proto-human ancestor might be alive in the dim recesses of the “Dark Continent.”

William Henry Johnson, a microcephalic Black American from New Jersey with a steeply sloping forehead and a pointy shaved head, wearing in a furry suit and carrying a staff, inhabited the role of Zip from at least 1865, when he was photographed by famous Civil War photographer Mathew Brady, until his death in 1926. In 1922, after Johnson, as Zip, put on a show of speaking “native Zulu” for newspaper editors and being frightened of flashbulbs, a reporter caught up with him on the sidewalk. “Great life, this wildman stuff,” he remarked. “I was in a crap game last night with the guy who took my photograph. I won. He lost. He ought to be the wild one.”

As historian Robert Bogdan explains, Johnson operated in a freak show world where “the outsider was held in contempt. Life was about tricking the rube, and making money.” Johnson may have been embodying a racist role, but he was also, in his own modest way, one of the most famous Black performers of his era: he had posed for a photographer who had also photographed Abraham Lincoln, and had performed for over a hundred million people over the course of his long career. The circus allowed Black Americans to not only impersonate Africans but to make good money doing so.

__________________________________

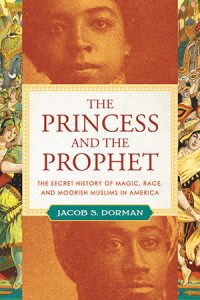

Excerpted from The Princess and the Prophet: The Secret History of Magic, Race, and Moorish Muslims in America by Jacob S. Dorman. Copyright 2020. Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press.