The Poetry of Tortured Hearts: On Taylor Swift’s Pre-Raphaelite Era

“Swift seems to be identifying with, and forcefully reimagining, this tragic figure from Victorian history.”

“Ope not thy lips thou foolish one

Nor turn to me thy face

The blasts of heaven shall strike thee down

ere I will give thee grace”

–Elizabeth Siddall, “Ope not thy lips thou foolish one”

*“I didn’t have it in myself to go with grace

And you’re the hero flying around, saving face

And if I’m dead to you, why are you at the wake?”

–Taylor Swift, “My Tears Ricochet”

*

In the August 2025 announcement of her engagement to NFL tight end Travis Kelce, Taylor Swift playfully likened herself to an “English teacher.” Indeed, her catalogue amounts to what we in the business of literary criticism might call astonishingly “intertextual.” Swift’s nods to 19th- and 20th-century writers are well documented. (See the excellent book-length study by Rachel Feder and Tiffany Tatreau). English professors are increasingly offering courses that situate Swift’s work in the literary context it invites.

For instance, Swift alludes to the Lake poets on her eighth studio album Folklore and speaks movingly of visiting William Wordsworth’s grave in her Long Pond Studio Sessions documentary. Swift commemorated Emily Dickinson with the release of her album Evermore on the poet’s birthday and Ancestry.com more recently posited that they share a lineage. Swift’s lyrics suggest a love for the novels of the Brontës and she has spoken effusively of Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility. Much has been rightly made of Swift’s fascination with Jazz Age novelists Fitzgerald and Hemingway, the Gothic writer Daphne du Maurier, and the poets Robert Frost and Dylan Thomas, among many others.

What we have not yet seen is a discussion of the ways that Taylor Swift’s pandemic-era writing, aesthetic, and album art draw meaningfully on the art historical and literary legacy of Elizabeth Siddall (1829-1862). Siddall (aka “Lizzie Siddal”) is perhaps best known as the auburn-haired beauty who posed as the Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais’s drowning Ophelia (1852) from Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The painting is so synonymous with Victorian culture it now graces the cover of The Norton Anthology of English Literature which is to say the 19th-century image of a Shakespearean “mad woman” singing to her watery demise has become a signifier for an era that has for years enchanted Swift.

John Everett Millais, Ophelia, 1851–1852

John Everett Millais, Ophelia, 1851–1852

Elizabeth Siddall’s career as an artist’s muse supports Edgar Allan Poe’s premise that “the death…of a beautiful woman is the most poetical topic.” Siddall died frequently in art. After Ophelia, she also modeled, for the Pre-Raphaelite painter and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), as Beatrice from The Divine Comedy and the Lady of Shalott for an illustrated edition of Tennyson.

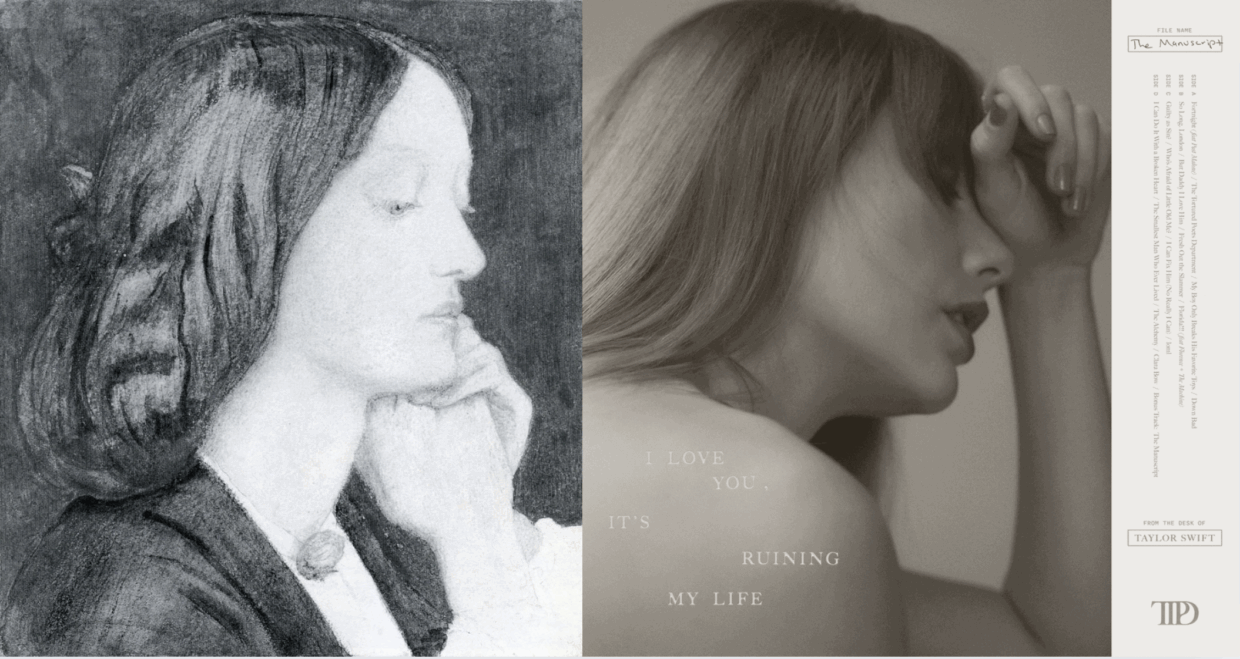

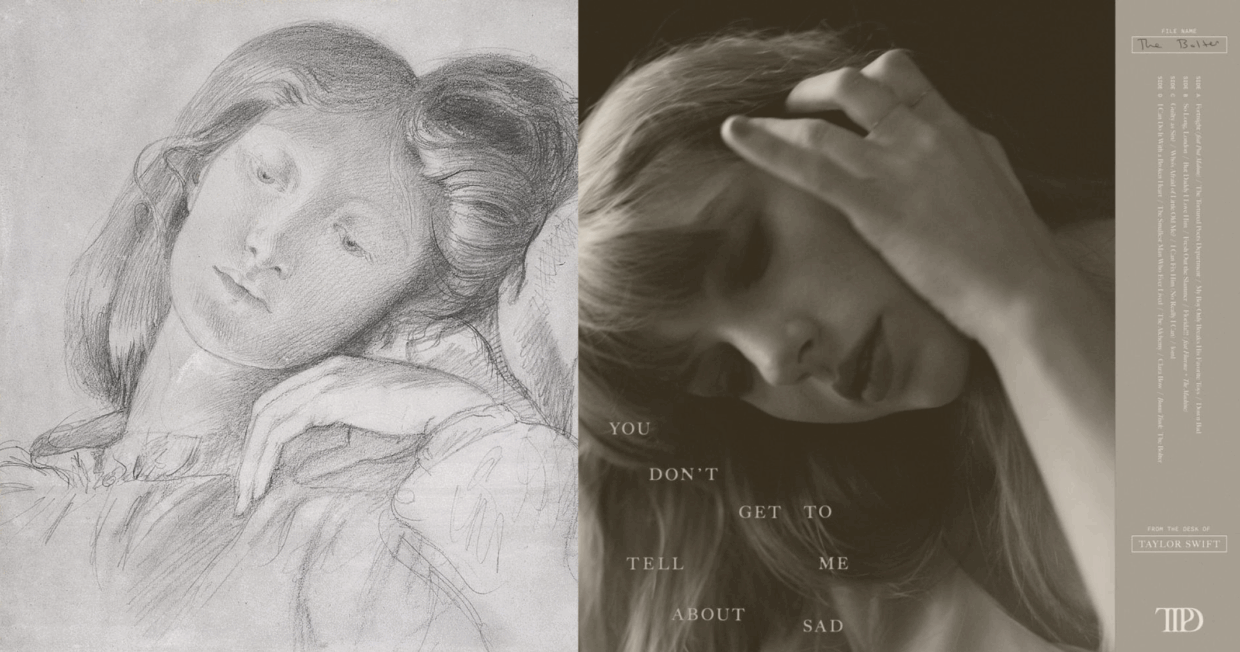

Taylor Swift seems to be channeling Elizabeth Siddall with the sepia-tinted images that went viral before the April 2024 release of The Tortured Poets Department. Those profile shots of Swift—flowing strawberry-gold hair, downward cast eyes, pouting painted lips, hand resting on face—poignantly echo Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s images of the melancholy Siddall, with whom the Anglo-Italian was involved in a notoriously tumultuous affair. Siddall was model, muse, pupil, collaborator, lover, and, for her last two years, wife to Rossetti, the son of an expatriate Dante scholar and brother to the famous poet Christina. Once they became an item, Rossetti arranged for Siddall to sit exclusively for him. Siddall’s unconventional beauty has been immortalized through Rossetti’s numerous paintings and sketches. In fact, a line from one of his poems reads like a self-fulfilling prophecy: “they that would look on her must come to me.”

At least as far back as her pandemic masterpiece Folklore, Swift’s lyrics have identified her as the rightful heir to Elizabeth Siddall’s story. The gaslit “mad woman” enduring a lover’s “quiet treason” (“mad woman,” “Fortnight”)? Check. A playboy who “gazes” at his beloved “starry-eyed,” hangs her picture on the wall, shows her off in public, then drowns in “stoned oblivion” (“The Smallest Man Who Ever Lived”)? Copy that. The “woman in the window” weary of a restless boy who promised to “grow up” and come back to her (“Peter”)? Yes. A lover who “stole her tortured heart” (“My Boy Only Breaks His Favorite Toys”), a refusal to “go with grace” (“My Tears Ricochet”), a reluctance to move on after heartbreak (“Right Where You Left Me”)? It’s all there.

Well-read in 19th-century poetry, Swift re-purposes the “tortured” verse of Rossetti and Siddall in her eleventh studio album. One Rossetti sonnet worships (the dead) Elizabeth Siddall’s “golden hair undimmed in death.” The gossip surrounding Rossetti’s macabre exhumation of Siddall’s grave to recover the manuscript with which he buried her, in a fit of grief or guilt, had it that her glorious hair filled the coffin after death. (The deed was done under cover of night and Rossetti was not present; he published the manuscript in 1870.) The Swift lyrics superimposed over her Pre-Raphaelite-esque head shots—“I love you, it’s ruining my life” and “you don’t get to tell me about sad”—could have been penned by Elizabeth Siddall herself. In one Siddall poem, the speaker’s “soul is not at rest” for having been “struck…down” by a lover’s treason:

I can but give you a tired heart

And weary eyes of pain

A faded mouth that cannot smile

And may not laugh again.

Knowing of Siddall’s premature death and the desecration of her grave, it’s easy to imagine her soul’s unrest. Siddall’s private poems share an uncanny kinship with the poetry of “tortured” hearts Swift folds into her 2024 album.

Swift, of course, has long loved London, and it is likely where she first encountered Millais’s Ophelia which hangs in the permanent collection at Tate Britain. Swift spent years in that city while romantically attached to the actor Joe Alwyn, apparently living for a time in Highgate not far from the site of Siddall’s grave (a tourist attraction for fans of Victorian art and literature). Swift seems to be identifying with, and forcefully reimagining, this tragic figure from Victorian history, particularly her work as a painter’s model and her confessional break-up poetry which is equal parts devastating and incandescent with rage.

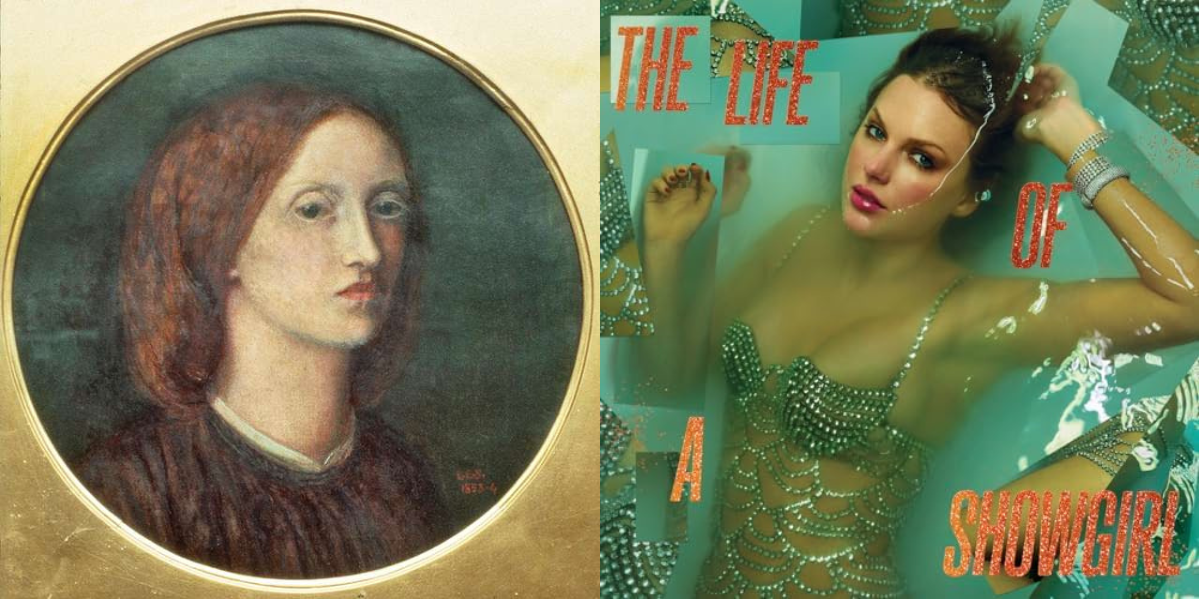

With the August 2025 reveal of the standard cover and track list for the twelfth studio album, The Life of a Showgirl, Taylor Swift provocatively revises Millais’s Ophelia. Swift positions herself as a modern Siddall with her obvious nod to the painting that made her famous. To embody Ophelia drowning, Siddall posed for Millais in a heavy embroidered gown, uncomfortably for hours, in a tub poorly heated by candles. As the story goes, the young Millais was so entranced by the creative process that he failed to notice the candles went out and Siddall, for her part, quietly suffered for art. The orange and turquoise accented Life of a Showgirl album cover features a coy, glamorous Swift in the jeweled costume of a Vegas dancer partially immersed in a tub that we can imagine is comfortably heated.

Unlike the surrendered arms of Millais’s Ophelia, Swift’s are raised in a way that suggests strength or self-defense—a welcome departure from the contorted torso that graced the digital double album cover for The Tortured Poets Department. Swift’s rosy complexion calls to mind the bittersweet admission “I’m just getting color back into my face” from “So Long, London.” Her hair is protectively pinned up rather than cascading down her shoulders like a Pre-Raphaelite muse. Swift appears to us upright rather than seduced, like Millais’s heroine, by the river’s pull. Perhaps most importantly, Swift’s arresting gaze, which meets ours, shares something with the sobering, steady look of resilience we find in Elizabeth Siddall’s startling self-portrait in oil. Swift is fully alive and in possession of her power. To borrow a phrase from one of her Tortured Poets bonus tracks, Swift has rewritten “the prophecy” of a 19th-century tragic figure like Siddall. She will control this narrative.

In releasing, the same day as the cover reveal, the title of the eagerly awaited first track, “The Fate of Ophelia,” Taylor Swift calls to mind something she uttered in “Fortnight,” track one of Tortured Poets, which is spoken in the voice of a “functioning” addict who was “supposed to be sent away”: “nobody noticed my new aesthetic.” Well, some of us noticed. Swift, shrewd social critic, close reader, and thoughtful consumer and maker of popular culture—a recording artist who numbers her tracks with intention—invokes Elizabeth Siddall, a functioning addict who could easily have been sent away, in order to critique the habit of enshrining, and thus silencing, creative women in art and popular culture.

To borrow a phrase from one of her Tortured Poets bonus tracks, Swift has rewritten “the prophecy” of a 19th-century tragic figure like Siddall. She will control this narrative.

Elizabeth Siddall is now recognized by scholars as a gifted artist and poet in her own right. As Jan Marsh, the leading expert on Siddall since the 1980s, has noted in the exhibition catalogue for The Rossettis, which the Tate hosted from April to September of 2023: “In recent decades, Elizabeth Siddal[l] has moved from a marginal to a near-central position in Pre-Raphaelite histories….[A]necdotes about Elizabeth are now essential elements in accounts of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.” The Rossettis retrospective illuminated Siddall’s contributions in water-color, charcoal, and oil. She produced over 100 drawings and paintings in one decade and earned the patronage of the Victorian art critic John Ruskin, who counted her among the five “geniuses” he had known in his life. Siddall’s watercolors drawn from legend, folk tale, and romantic poetry (e.g. Lady Affixing Pennant to a Knight’s Spear, Lady Clare, Clerk Saunders, St. Agnes’ Eve) are also now rightly critically acclaimed. Siddall’s verse, originally published in the 1890s by a brother-in-law who thought little of her talent (but capitalized on her posthumous appeal), is now available in Serena Trowbridge’s superb 2018 edition which restores her manuscripts and poem titles.

But Siddall—whom Rossetti re-christened “Siddal” thinking one “l” diverted attention from her working-class roots—was born too soon and did not emerge from the 1860s alive, though her image as a 30-something beautiful death by overdose, and the mythology attached to it, enjoyed an afterlife she never could’ve imagined. Taylor Swift’s engagements with the 19th-century figure of Elizabeth Siddall—her drug-addled and much-celebrated wasting body, her legendary hair the stuff of poetry and myth, her modeling career, her artistic oeuvre—show the for-years marriage-free and child-free musician to be offering an enlightened revision of the tragic muse in her 21st-century body of work.

Now, to set the record straight on Elizabeth Siddall, whose biography is clouded by misinformation: ever since her untimely demise in February of 1862, popular culture across the Atlantic has been obsessed. By the 1890s Siddall, who expired from a likely intentional overdose of laudanum, the uncontrolled opiate to which she was addicted, became a kind of cult figure worshipped by the 1890s decadents, namely Oscar Wilde and Algernon Charles Swinburne, a friend of Rossetti and Siddall who is said to have been to dinner with them the night she died. There is evidence that she suffered a stillbirth and possibly a miscarriage shortly before her death and a suicide note may have been destroyed to ensure a Christian burial.

Elizabeth Siddall has been on Swift’s radar at least since June 2019 when her close friend, the writer and actress Lena Dunham, devoted a podcast to the Pre-Raphaelite model and muse. Co-hosted with Alissa Bennett, the program sets out to correct the record on women who have been historically written off as “crazy.” Additionally, Swift’s collaboration on Tortured Poets with the British singer Florence Welch who has reimagined herself as Beata Beatrix (Blessed Beatrice) and an open-eyed and self-aware Ophelia for her own album art, reminds us Swift has been moving in Siddall’s orbit for some time.

As recently as July 2025, a character on Dunham’s Netflix series Too Much, set in contemporary London, perpetrates the myths attached to Siddall without naming her, much in the way her first biography was simply called Rossetti’s Wife. In one episode, a fashionable wedding guest boasts on her lapel an item she calls “a Victorian hair pin” which “holds a lock of hair from Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s lover” (they were married when she died, which would occasion the clipping of hair as keepsake), says “she was poisoned by laudanum” (not exactly), and that “he kept her body for three days praying her back to life” (nope, but there were unseemly rumors he painted his Beata Beatrix from her propped up corpse). If that pin really held a lock of Siddall’s hair, which Mark Samuels Lasner has called “the most iconic hair in art history” and which was recently on display in the Rossettis exhibition, it would be worth untold thousands.

One need not be a Swiftie to see that every artistic move Taylor Swift makes is executed with thought and purpose. In a song that presents herself as a “mastermind,” she suggests she’s “only cryptic and Machiavellian because” she “cares.” The curated photographs announcing her engagement to Travis Kelce are shot in what seems to be his backyard which is staged to resemble an English country garden. The pink and white roses suggest the English painter John William Waterhouse who was a kind of heir to the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic. Swift is empowered and in control. Her fiancé kneels before her on bended knee in a gesture that calls to mind the 1901 painting The Accolade by Edmund Leighton which depicts a standing queen making a man a knight. Swift wears a simple and tasteful black-and-white striped Ralph Lauren midi dress.

Could Taylor Swift’s sartorial choice be a nod to Elizabeth Siddall’s striped frock in one of her only surviving photographic images, easily accessible on a Google search? That would be a progressive move suggesting Swift is identifying with Siddall as she was, not as she filled her (tortured?) artist’s dream. All signs suggest that Swift is transitioning into a new “era” that re-writes the tragic, betrayed, and broken muse and makes her a writer, a speaker, an artist, and a queen who knows her power. Enough with “the sad sight” of the woman abandoned at the restaurant in “Right Where You Left Me.” The cover image on Swift’s forthcoming album suggests that the woman returning our gaze has no patience for the love-games about which Siddall writes in one of her finest poems:

Low sit I down at my Ladys feet

Gazing through her wild eyes,

Smiling to think how my love will fleet

When their starlike beauty dies

One can imagine Swift would be pleased to see Siddall’s manuscripts restored given that she labored for years to acquire the rights to her own masters.

The Life of a Showgirl will be released October 3, 2025. Any Swiftie can tell you that 10 (October) plus 3 (the third) adds up to her favorite number 13. (Born December 13, Swift shares the same zodiac sign as Emily Dickinson and Jane Austen.) One thing is certain: nothing Taylor Swift does is careless. Perhaps another announcement is forthcoming on February 11, the 164th anniversary of Elizabeth Siddall’s passing. I’m going with that, as 2 (February) plus 11 (the 11th) is, well, guess. The Swiftie in your life will be enchanted.

Emily J. Orlando

Emily J. Orlando is the Corrigan Chair in the Humanities & Social Sciences and Professor of English at Fairfield University. She is the author of Edith Wharton and the Visual Arts and editor, most recently, of the first annotated edition of Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman’s The Decoration of Houses, an excerpt of which appeared in Lit Hub. She has been publishing on Elizabeth Siddall and the Pre-Raphaelites since the late 1990s and recently developed a course on Taylor Swift’s literary eras.