The Poetics of the Body: An Interview With CM Burroughs

Peter Mishler in Conversation With the Author of Master Suffering

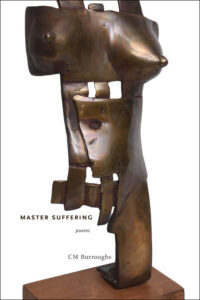

In this next installment of our series of interviews with contemporary poets, Peter Mishler corresponded with CM Burroughs. Burroughs is Associate Professor of Poetry at Columbia College Chicago, and is the author of two collections: The Vital System (Tupelo Press, 2012) and Master Suffering (Tupelo Press, 2021). Burroughs has been awarded fellowships and grants from Yaddo, the MacDowell Colony, Djerassi Foundation, Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and Cave Canem Foundation. Burroughs’ poetry has appeared in journals and anthologies including Poetry magazine, Callaloo, jubilat, Ploughshares, VOLT, Best American Experimental Writing Anthology, and The Golden Shovel Anthology: New Poems Honoring Gwendolyn Brooks.

*

Peter Mishler: Could you talk about a key development or experience in your life as a poet that, looking back on two completed collections of poems, appears to have been life or art changing?

CM Burroughs: As a young woman not yet out of college, I was accepted to Dr. Charles Henry Rowell’s Callaloo Creative Writing Workshop, a summer workshop retreat where I worked with my earliest mentors, Reetika Vazirani and Natasha Trethewey. It was also where I worked with a brilliant poet who has become one of my best readers and friends, Douglas Kearney. Reetika and Natasha challenged my poetry and guided me as a woman in the field, and Douglas, who was an emerging writer and scholar at the time, taught me how to articulate what I wanted my poetry to do and what I wanted to do with my poetry. Having these forces in my life meant that I became serious about my career trajectory; it was then that the great shift in my mind came—I changed my career path from becoming a lawyer to becoming a poet. I had the intuition that the revised direction was the correct direction.

PM: What is the strangest thing you know to be true about the art of poetry?

CMB: I’ve always felt that my understanding of my body, body-history, and my form’s movement through space over time are vital for the development of my poetry. That helps me to produce an embodied work for the reader to occupy. I believe in creating space for readers within my poems.

I’ve always felt that my understanding of my body, body-history, and my form’s movement are vital for the development of my poetry.PM: What approaches to poetics of the body—or particular poets who do this work—have been particularly guiding or instructive for you?

CMB: I appreciate and am impassioned by poets whose work expresses urgency. The poets cycle, but the current books that are front-facing on my bookshelf include Douglas Kearney’s Patter, Molly McCully Brown’s The Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, Tracy K. Smith’s full catalogue, Jennifer Jackson Berry’s Feeder, Claudia Rankine’s full catalogue, Tarfiah Faizullah’s Seam, and Jericho Brown’s The Tradition…this list goes on. Conversations with these and other poets—through their books and through friendships—is vital for me in times of thought and composition. Hélène Cixous is the scholar to whom I feel most connected; her work and the ghosts of her work reside in me and are constantly nourishing.

PM: Would you be willing to say more about this common urgency you are drawn to?

CMB: I appreciate the present—the construct of time—so poetry that accesses the current moment (whether in it or crossing through it) attracts my want to occupy that space.

PM: To what extent do you think that a poet can cultivate the familiarity and awareness you articulate above?

CMB: Empathy is the first thing anyone should foster to address the body in poetry. Cultivating empathy requires one to have relationships with kinds of bodies Other than their own. My relationships with bodies unlike my own have happened organically over the course of my life. But I do believe people can actively seek the unfamiliar or dissimilar in order to widen their experience and develop their perspectives of the body.

PM: Would you be willing to share some of your experiences as a poet that led you to your thinking about what poetry requires? In what way, does Master Suffering seem to exhibit these qualities in the poetry itself or in the making of the collection?

CMB: My experiences as a person have informed what I believe about poetry. Master Suffering thinks deeply about my younger sister who was overcome by a long-term illness at age 11. The life one leads is determined by what her body can do, how precisely it works, or, in the case of fatal illnesses, cannot or will not work. The series of poems “Dear Liver” interrogate her organ—the liver and its replacement—that failed her, personifying the organ with will power, control, and intent.

PM: I’m very sorry to hear you’ve experienced the loss of your sister. In these “Dear Liver” poems, this act of interrogation, would you be willing to share what you think this poetic act yielded for you in your grieving and loss? Or were there aspects of writing about your sister in which you recognized something, a power, of writing lines that you hadn’t anticipated?

CMB: My greatest insight during the writing of Master Suffering was my composition of poems about cleaning. I simply began thinking about cleaning because it is an action I have always performed as meditation and instant gratification, and it was only after writing the poems that I shifted to writing about my sister. The moment of magic, however, was when the meditation of my life—cleaning—and the meditation of my sister’s body—the wellness of her liver—came together. The liver’s function, after all, is to clean. I used the epistolary form because I had questions that I couldn’t answer and the only way to prompt the conversation was to write to the liver(s) directly.

PM: Looking back at your first book The Vital System in relation to Master Suffering what relationship do you notice?

CMB: The Vital System is a book that is very much about transitions through vulnerability while desiring strength and dreaming destinations of power. Master Suffering is a book of speakers who have come into their power and now must reckon with what it means to decide/choose/stake. The books access different parts of my poetic voice, as well; The Vital System uses the lyric form as the speaker moves through sometimes opaque sites of development—the incubator of my birth, race, sensuality, and sexuality. Master Suffering is a book with enough power to speak plainly, to offer openness to the most difficult subjects—death, grief, mental illness, and what sustains a woman through these hardly bearable life experiences. I love what both books are, and I enjoy that Master Suffering marks an evolution of speech.

PM: One of the striking aspects of this collection are the direct addresses to dear friends included in some of the poems. Could you comment on that aspect of your work?

CMB: The “God Letter” series of the book was a favorite accident of mine. The first poem I wrote was for my friend A. Van Jordan. I simply journaled after we’d had an impromptu conversation about religion. I was dating a Christian at the time and trying to figure out how to reconcile my agnosticism with his belief in God (he had invited me to church.) Van provided a great sounding board for my wonderings, and then came the poem of that conversation. The epistolary form was (and is) so kind to a poet who needs to talk. My first book, The Vital System, contains a poem, “Dear Incubator,” with the final line, “believe me, I mostly want to talk.” That want to talk remains true.

PM: Read as a collection exploring the complexity and trials of faith, did completing the collection or the process of writing the collection bring you somewhere new in this regard? Is there a “poetics of faith” or poets or poems who have been particularly inspiring or guiding for you in your work?

CMB: Wrangling with faith in my book did not bring me closer to God, but it did help me to understand why others believe. I had to root through my past in order to watch how God did and did not figure into the experiences of my youth. Many people decide that loss and tragedy is a reason to believe harder and with more conviction. My own loss and tragedy simply caused me to question where belief comes from in the first place, and to discard the receptacle, religion, that could not harness or salve my pain.

PM: Would you be willing to share your relationship to the epigraph by June Jordan, and the ways that quotation speaks to you: “What do we do, those of us who did not die?”

CMB: June Jordan’s words foreground a fair question for all who grieve and live beyond the loss of loved ones. There is a monumental adjustment between having and not having, being with and without; much of that adjustment rambles rabidly through the mind, but the rest is unbearably physical. People make such a tangible mark upon the spaces they inhabit…what to do with that, all that remains? Jordan’s quote questions the immediate aftermath of loss and the years following. Master Suffering is my answer to Jordan’s question.

PM: Could you talk about the process of organizing this collection and how you thought about colliding or interweaving its various parts, themes, or approaches?

CMB: Trauma doesn’t naturally dance. But after some time, after some healing, it ought to try. The organization of the book accomplishes the nature of acrobatics, movement, and agency that I needed in order for the book to find lightness. I didn’t want the entire book to mourn. The counterintuitive mixing of themes within sections is another actor against stillness.

__________________________________

Master Suffering: Poems by CM Burroughs is available now from Tupelo Press.