At home, I woke up in the middle of the night, turned over for a while, gave up on the acrobatics, and got up. Apparently watching Richard die at work didn’t improve my sleep patterns. I did a lap around my apartment, which consisted of three rooms and a bathroom. A bedroom with a bed on one end and the largest closet I could afford on the other. A small room that doubled as my living and dining room in the middle, and a half row of cabinets over a stove that served as my kitchen. Every square inch of wall was covered with ripped-out pictures of Black models serving looks in everything from disco wear to modern gowns, except for the space over my bed, which had a huge Coffy poster, just in case Pam Grier cared to lend me toughness while I slept. I desperately wanted to keep this apartment for the privacy and because it was the only thing in my price range that had a closet big enough that it could house a sleepy Bengal tiger. But my rent was due to go up in a couple months, and my student loans were a sword swinging just above my head.

I went to my bedroom window and took in the busy three a.m. world outside. The people who worked at the night taco stand down the block were dishing out cheap al pastor tacos from a spit under a lamp between two sets of homeless encampments. Packs of teens, free for the summer, ate tacos while leaning on their cars and playing music with their windows down. The two lanes of traffic that ruled my corner of East Hollywood whooshed by with their normal nighttime hum. I took the pair of binoculars from their resting place on top of my dresser to spy on the people eating at the upscale Mexican restaurant across the street. Once upon a time, when I first landed in LA, I convinced myself that I would become an outdoorsy person beyond the act of leaving my apartment to get into my car. So I’d bought the binoculars, positive that a bird-watching future was on my horizon. But instead of watching birds, I mostly used the binoculars to try to figure out what the fancy Mexican place could possibly put in their margaritas to make them cost twenty bucks. Caviar? Liquid gold? I longed for the kind of cash that would let me waltz into that place and be a different person, a richer one, ready for the elegant experience of consuming expensive enchiladas. Just thinking about their food reminded me that I hadn’t eaten anything since Richard died. My money situation seemed even darker than usual thanks to his death.

I went to the kitchen, put on the kettle for barley tea, and grabbed a bowlful of the mangoes I dried in strips out my own back window to avoid paying the shakedown grocery-store prices for the same thing. Yeah, I’ve stolen things on occasion, but the real hustle is grocery stores. You walk in with your wallet and they’re like, nope, we’re taking your car.

Three mango strips in, I remembered the watch money. There it was, in my work pants, a pack of hundreds that would briefly let me pretend I could live a different life. A slightly more cash-laden spin around the sun. My watch guy had coughed up $975, so I was feeling like an heiress who had just inherited an oil refinery. But the real treasure he gave me was a fake gold coin. He said it was worth the last twenty-five dollars of what he owed me. At first I tried to get him to give me the cash, but then I took a look at the coin and got sucked into its world. On its front it said All Them Hills Are Gold, and on its back it said Twenty-Five Diner Dollars on top and Gold Leaf Diner on the bottom. In the middle it had an address on Pico for a twenty-four-hour diner well west of me but not quite all the way to Santa Monica. The fancy Mexican restaurant across the street from me wasn’t anywhere near cool enough to mint its own fake gold coins. I loved the coin, because just like the money, it spoke to a slightly different life, but one I could drive to and discover. Who went to a diner that minted its own coins?

The coin inspired me to move to my bedroom and open my closet, where I stored fifteen years’ worth of fashion, from my post-college days when I thought I might become a clothing designer to all the clothes nobody else wanted on film sets. I was ready to follow this coin to its diner and temporarily become someone else, even if that other person was simply someone who went to faraway diners. I often got sick of being myself, a thirty-nine-year-old failure who worked in a mall and spent most of the rest of my time at home drying mangoes and killing ants. When I picked something out of my collection, I could go back to who I had been then, or whoever had given me the clothes, or imagine the mysterious lives of the people who had left key parts of my wardrobe for me to find at thrift shops.

I pulled on a bobbed fuchsia wig with heavy bangs, and my favorite catsuit, one of the leftovers from after we finished filming Catwoman: Cougar’s Revenge, a movie that came out a few years back. I’m sure a couple dozen people remember it. Catwoman robbed a few banks, but her biggest crimes were falling in love with a man with a fatal allergy to commitment, and being forty-five. Absolutely no one else wanted the catsuit, which was several thousand layers of black lace piled on top of each other from neck to ankles. It made the woman who played Catwoman look like a very dangerous and also mysteriously tight-fitting set of drapes. The movie flopped, so we couldn’t auction the catsuit off or anything, and the costume shop I found it in didn’t want to take it back after they discovered Catwoman had made a few cuts in the sleeves, probably as revenge for realizing the movie wasn’t going to get her out of a career slump. So it was mine. I got in my car with the coin to drive to the Gold Leaf Diner.

If you drive at the right speed down a mostly commercial street, LA can become one long strip mall. Some people think that’s terrible, but I don’t. The strip malls give the city a deck-of-cards look. I liked gazing into those rectangles, seeing all their different combinations. At three a.m. the long strip mall was mostly closed, but there were pockets of light. I passed a pack of people eating donuts on the hood of someone’s car. I passed a closed body shop with cars so broken down they looked like mouths with missing teeth. I passed a couple kissing under an old-school neon-palm-treed hotel sign from some period of LA history when they must have been trying to sell Midwesterners on the place. UTOPIA MOTEL, the neon sign gently murmured into the night. NOW WITH HBO.

I settled into the idea that I’d be driving for a while and put on music. I kept a magnet in the car I could mount my phone on for musical emergencies. The only proper three a.m. music is disco. I put on “Knights in White Satin” by Giorgio Moroder and just like that, the night became sexier. Everything now looked to be lying on top of everything else, like the strip malls and apartments had just enjoyed a good time together. Closed corner stores lay on top of closed pizza places, which got down with closed barbershops. The Moroder faded into Diana Ross, which gave way to Sister Sledge. In the middle of the night, we are all the greatest dancer.

The diner looked like an ordinary diner at first glance, with a long, rectangular parking lot oozing out its side like a half-used tube of toothpaste. But the front of its building held the same design as the front side of the coin. ALL THEM HILLS ARE GOLD, the diner glowed to the closed drugstore across the street. Both of them sat on a stretch of Pico where hills were merely an idea. The logo added mystique to an otherwise straight-from-the-diner-handbook-looking place. The history of gold was full of death and folly, but every once in a while, someone struck it rich. Nine hundred seventy-five extra dollars felt good, but man, what I wouldn’t do to suddenly have a lot more money. Please, diner, give me some luck.

I didn’t notice the cops until I’d already sat down in a booth. I didn’t dine with cops, but after a waitress handed me a menu, it felt too late to switch booths, and if I tilted my head at the right angle, I couldn’t see them. I ordered coffee and hash browns, and the waitress slid them in front of me just when I’d become bored enough to try to figure out if they were city or county cops. But their badges looked all wrong. What the fuck kind of cops wore turquoise badges? Clearly the ones who had just come back from Sedona ready to tell anyone who’d listen about some crystals they bought that would fix climate change if they held them in the right order.

The diner didn’t have Cholula, but it had tiny appetizer-sized bottles of a homemade habanero hot sauce that worked on top of the ketchup and black pepper on the hash browns. The coffee tasted like good dirt. Yes, I was one of those kids who ate dirt, and at its best, dirt is layered with notes, like a good glass of wine. So I ate hash browns, and drank delicious dirt coffee, and would have ignored the cops if they weren’t so damn loud.

The loudest cop had a real cop face. Some might say punchable, but not me, because I’m an upstanding member of polite society. He worked himself up into a real crimson glee as he described a single mother who had unfortunately found herself in some kind of debt, which struck me as odd, because I didn’t think anyone referred to anything cops had to do with—say, traffic tickets—as debt.

“Just thousands of dollars of debt,” he said, excited. “She thought the monthly minimums were a suggestion.”

The other two cops laughed.

“What kind of deadbeat can’t even pay the monthly minimums?” said a cop with the kind of lantern jaw and floppy white-guy hair I associated with lacrosse players. Hot white cops were such a waste.

“I know! You can negotiate them down to like, two dollars a month for the rest of your life,” said a Black cop who’d wasted his gorgeous, Idris Elba–esque mug on law enforcement.

There’s no need to talk when you’re eating alone, but the sight of a Black cop merited an extra moment of silence. Even good-looking Black cops are the mouse that’s just taking a nap in the snake’s mouth.

Wait a minute. Two of the cops were hot. I took another look at the group. They all looked pretty together for cops. I mean, cops couldn’t really be hot because of what they did, but these guys all had a look I wouldn’t have disapproved of out of uniform. Why were they hot?

“Oh, no, I think they stopped that. You have to pay at least a hundred a month now,” said Lantern Jaw.

“That’s not that bad,” said Black Cop.

“Yeah,” said Lantern Jaw. “You can just cut your own hair.”

“Or make your own coffee,” said Black Cop.

“Or get another roommate,” said Punchable Face.

“Or a third job,” said Black Cop.

“They’re just so lazy,” said Lantern Jaw.

I listened to this line of conversation in total disbelief. These guys had clearly never tried to do shit like work multiple jobs, afford an apartment, and pay their loans at the same time. I was doing a hair better than that now, but I remembered darker days. I could tell them stories of my heroic, Oscar-winning performances for roles like “woman insists this pound of beans will last three weeks,” and “shoe soles are for cowards.” I remembered the nights where I had to travel between far-flung jobs fueled on coffee, 5-hour Energy, and the fear that I would nod off long enough to end up pancaked on the side of the 101.

“After I held one of her kitchen knives up to her throat, she suddenly remembered how to pay her debts,” Lantern Jaw said.

The other two cops laughed. But I froze, with my fork-holding hand halfway up to my mouth, unable to move. They laughed and laughed and laughed, and all their laughter stabbed me in the stomach.

I, unable to listen to their conversation for a second longer, signaled for the check, handed over the coin, and headed for the door. Like a lot of diners, this one had two sets of swinging glass doors.

Inside the first one I looked left and saw the vending machine I’d missed on the way in that sold commemorative diner coins like the one I’d just had in my pocket, which felt so much less intriguing now that I’d discovered that they came from a vending machine that would sell you one if you put in twenty-five dollars and had the skill to grab it with a metal claw. Nothing in those hills was gold.

I slung myself into my car and sped off. I don’t know who I expected to find eating at the diner, but definitely anyone else other than a pack of cops dickish enough to laugh about threatening a single mom. And nothing wrecks the mood like listening to people talk about punishing others for their debts when you haven’t paid yours off. My undergrad and film school debt followed me around like a stalker in the night. My debt eagerly anticipated this next part of my life where I might not have a job. Debts loved that shit. They could just sit there, multiply, and laugh while I tried to come up with contingency plans. As a person whose adult income tended to range from low to embarrassing, I’d paid the minimum when I could afford to and turned away whenever the loan website tried to show me how much I owed. But cops didn’t seem like the kind of people who made enough money to brag about people who couldn’t pay debts. Every year the news claimed they were underpaid, so they needed more money to beat people up and not solve crimes.

Either those cops were rich enough to despise us debtors like they did people who’d shoplifted a candy bar from the drugstore, or they were broke enough that they were right there in the stew with us. I made it home and went to bed, positive I’d be exhausted enough from all the driving to immediately drop off to sleep. Instead I rolled around forever, simmering in dread and a lingering sadness from Richard’s death, praying I’d never fuck up enough to have to deal with those cops or their criminally ugly turquoise-ass badges ever again.

__________________________________

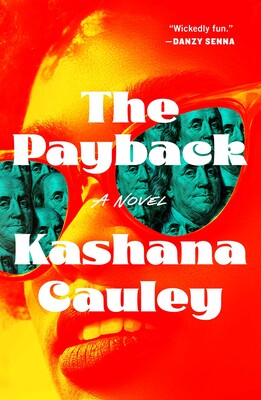

Excerpted from The Payback, Copyright © 2025 by Kashana Cauley published by Atria Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.