My name is Czesław Przęśnicki, I’m a miserable Eastern-European immigrant and a failed writer, I haven’t engaged in sexual relations for some time, and I’ve been committed to an asylum in Belgium, a country that has had no government for the past year. The reasons I find myself hemmed in by the cold walls of a psychiatric hospital in the north of Europe are as mysterious to me as the failure of my sex life, which has had me languishing in apathy and frustration for years. When I was born 35 years ago behind the Iron Curtain in the confusing geopolitical space marked by Adolf Hitler’s hyperactivity, nothing foretold that I would end up in a Belgian asylum one day. To be precise, the state that issues my passport is Poland, country of globe-trotting popes, frigid temperatures, and muscular war heroes among whom, hypocrisy aside, I don’t count myself. I have a submissive nature, a flaccid body, and am thinning on top, and my faint-hearted self falls a long way short of exuding sex appeal for healthful fellow specimens of the male sex, whether under totalitarian regimes or democracy. Before I was committed to the psychiatric hospital of Liège, a city located in francophone Belgium, I lived in Vinson, the capital of Antarctica, where I shared the sad destiny of other miserable Eastern-European immigrants who set foot on that white continent clutching their newly acquired passports. That was how I learned Antarctic, a language I now speak fluently, though with a strong foreign accent, which I employed to write my first novel, Wampir, a critical and commercial failure.

Despite having published a book, I never wanted to be a writer but a veterinarian, and I can only blame the injustice of fate for the fact that I haven’t been able to follow my one true calling. Perhaps that noble profession would have led me down other paths in life and, instead of now finding myself confined to an asylum writing a novel, I would be engaged in activities more constructive than literature. Yet we writers write for reasons that spring from our moral turpitude, to wit: ambition, an inflated ego, anguish, a desire to shine, arrogance, and fear of death. These dramatic circumstances spur our progress on the stories we present to our readers, innocent and generous souls who pay out of their own pockets to bestow on us a few hours of their lives. We tend to disappoint them because, as goes for the entire human race, among which weak and depraved examples of the species predominate, those of us who write badly far outnumber those who write well.

But my dream has always been to be a veterinarian, and throughout my communist childhood there was nothing to suggest that one day, instead of working in a clinic packed with unvaccinated dogs, I would be confined to an asylum in Belgium, a country that has had no government for the past year. Back then the days behind the Iron Curtain passed without incident, and as the years went by I devoted myself to lining up to buy toilet paper and fantasizing about attaining a passport. Everything got complicated when the Wall fell and we citizens of communist countries, until then habituated to the daily hunt for essential items, had to face the vast universe of possibilities that was the free market. Vices and debauchery came to Poland along with the Western multinationals, and in those new geopolitical circumstances I fell in love with a US citizen named Ernest Hemingway. Ernest, who was in Poland teaching boxing lessons in a school in Cracow, likewise took an interest in my flaccid self, and not long after we moved in together. Hemingway and I were very poor and very happy in our Cracowian flat, but the following year Ernest was offered a chance to teach boxing at the University of Vinson, the capital of Antarctica. Given my devotion to sex, I followed Hemingway to the white continent, where, due to the dearth of places in veterinary sciences, I enrolled in Antarctic language and literature. In Vinson we led a quiet life until the day Ernest upped and shot himself, leaving me nothing but a confusing farewell letter about a lost generation, the restroom of a Parisian bar, the two world wars, the Spanish Civil War, and a young soldier who tried to escape by bicycle. I spent the months following Ernest’s suicide listening to Maria Calla’s performance of Bellini’s aria Casta diva, reading Nietzsche, and for the first time contemplating the concept of eternal return, never suspecting that it would prove untrue with respect to the future prospects of my sex life.

I realized too late that speaking foreign languages leads to madness and that those who speak languages end up unhinged.Despite all this I remained in Vinson and some years later graduated with a degree in Antarctic language and literature, not because I was interested in literature but because I had a student visa and so needed to continue studying to avoid being ousted from the country. What I was interested in was learning languages, for I nurtured the hope that speaking Antarctic and another language would not only help me integrate abroad but would also make me a polyglot or a happy person. Nothing could be further from the truth, given that for some time I’ve found myself languishing in sexual abstinence and confined to an asylum in a country that has had no government for the past year. The few pleasant moments I experience in the Liège psychiatric hospital are those I devote to my second novel, which I started writing on some old pages of the Flemish daily De Standaard. I found this Dutch-language newspaper beneath my bed and at first I used it in the absence of another medium but, in time, filled as it was with words in a language I can’t understand, it ended up tranquilizing me more effectively than the medication the aides provide.

This was because for many years I thought, in line with the social propaganda I absorbed from a tender age, that speaking foreign languages was a cultural treasure, a privilege, and a stroke of luck. I had read several quotations on the subject by admired intellectuals such as Goethe, who said a man is worth as many men as foreign languages he possesses, and he who does not know a foreign language knows nothing of his own. Today I know that, apart from writing literary works, Johann Wolfgang studied the intermaxillary bone, but he was not the only one who bombarded me with irrefutable arguments in support of learning foreign languages. Education ministries and universities also assured unsuspecting citizens that speaking languages was a guarantee of both professional success and a satisfying personal life. I myself believed in those tall tales for years, realizing too late that speaking foreign languages leads to madness and that those who speak languages end up unhinged. Suffice it to consider the fate of the multilingual Karol Wojtyła, who spent years traveling the world draped in a white dress and living in the most touristy spot in Rome. While the worst that can happen to one who doesn’t speak languages is being served the wrong dish in a restaurant abroad, the opposite scenario can mean ending up in the Vatican or being shut away in an asylum. At this stage of my miserable life I know that speaking languages only leads to bitterness and for this reason I am writing my second novel on some old pages of the Flemish daily De Standaard, Dutch being a language I don’t know and one that therefore inspires in me tranquility and peace of mind.

I had to stop writing because my roommate, Father Kalinowski, finished his evening prayer, slipped off his cassock, blessed me, and switched off the light. Before being committed to the Liège psychiatric hospital, the priest lived in a block of flats in a mining town in the south of Poland and, aside from celebrating mass, he tended an allotment garden on the outskirts, where his five chickens pecked out an existence. Father Kalinowski is in the asylum due to a mysterious collapse he doesn’t wish to talk about, and he spends his days praying, training on the stationary bicycle we have in our room, and listening to the radio, which he tunes to the Polish episcopacy station. Our cohabitation is difficult due to both the insomnia that torments the priest at night and his frequent prayers for the salvation of my soul, which he tends to carry out in the middle of our modest living space. Today he has fallen asleep and I have lain awake a long time, listening to his quiet breathing and fantasizing about leaving the Liège psychiatric hospital one day, engaging in sexual relations once more, and devoting myself to comforting domestic animals in a small clinic on the outskirts of Vinson.

__________________________________

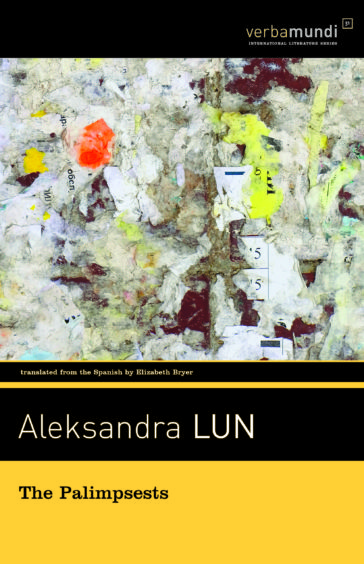

This excerpt of The Palimpsests first appeared in the Spring 2017 issue of Asymptote, the premier online magazine for world literature. The Palimpsests is now available from David R. Godine, Publisher.