The Paddystinians of Belfast: On the Palestinian Solidarity Movement in Northern Ireland

Philip Metres Examines the Close Bonds of Occupation

I couldn’t believe my eyes: not one, but bunches of Palestinian flags kept appearing, every time we turned onto another Belfast street—waving at me, beckoning, inviting me into their story. It was 2011, my first trip to Northern Ireland, and I was amazed. I’d never seen so many Palestinian flags. When I asked Bill Shaw, a Presbyterian minister, about the flags I saw outside an apartment window near his church, he told me, “That’s where the nuns live.” The flags seemed like oases, little signs of welcome, in a desert world that did not see Palestine.

I’ve been wondering about them ever since, all those flags, since I began leading our annual university peacebuilding program to Northern Ireland. The Irish and British flags, of course, made sense, fluttering on poles and in front of houses and businesses in the working-class neighborhoods where the Troubles had been most violent. But the Palestinian ones that waved at us on the streets—I gazed upon them with awe.

Growing up in the United States in the 70s and 80s, I’d heard little of Palestine. It wasn’t until my sister came back from studying Arabic at Bir Zeit University in 1993, that I learned for the first time about the Palestinian story, as well as the depths of the terrible silence, the blinkered deliberate unseeing that defines the American empire. To recognize Palestine was to talk of the emperor’s naked body, exposed—something that no one would acknowledge, pretending that it was covered by majestic new finery, another state entirely.

Ten years later, at my sister’s wedding to Majed in Palestine, I was able to witness Palestine myself. A longtime advocate of peace and human rights, I made it my job, inside the classroom and out, to raise awareness about the Palestinian struggle. It’s only been in the last two years when that movement has become well-known to the wider United States.

When I first arrived in Belfast, I saw both Palestinian and Israeli flags, but in different neighborhoods—the Palestinian ones in Irish nationalist areas, and Israeli ones in Protestant loyalist areas.

So back in 2011, I couldn’t help it—awe overtook me as I walked along the Falls Road, seeing so many signs of Palestinian solidarity. A few years later, at the Sinn Fein bookstore, I bought a rubber wristband with the Palestinian and Irish flags, and the words, “Free Palestine” and “Save Gaza,” wearing it back home.

I recall, with shame now, my own discomfort, when walking in my Orthodox Jewish neighborhood, wondering if it would mark me as different, or enemy.

*

Flags in Belfast are more than just flags, and more than just markers of identity. They mark territory and cultural connection: the Irish tricolor often appears in Irish-identified working-class areas, while the array of British and Ulster flags (not to mention illegal paramilitary flags) fly in British-identified working-class areas. Around the Twelfth of July, the traditional celebration of King William of Orange’s defeat of the Catholic James II, the unionist community is so bedecked with flags it looks as if whole streets could hover in the wind.

So when the British flag came down from Belfast City Hall as a result of a vote by the city government in 2012, loyalist protests broke out, leading to an attempted storming of the building. It was pointed out that nowhere else in the United Kingdom did the flag fly every day; but in Belfast, it always had. Belfast was British, the loyalists said, even more British than the British!

When I first arrived in 2011, I saw both Palestinian and Israeli flags, but in different neighborhoods—the Palestinian ones in Irish nationalist areas, and Israeli ones in Protestant loyalist areas. When an Israeli filmmaker asked a local why he was flying the Israeli flag, he shrugged and said, “I have that flag because it bothers them (Catholics) over there.”

Even if this loyalist wasn’t able to articulate the ideological connection, the broader Protestant/unionist/loyalist community does have an affinity for Israel and Israelis; both peoples, from their vantage point, see themselves as minority communities under siege, victims of terror. The October 7th attacks spurred a proliferation of both Israeli and Palestinian flags.

Perhaps there’s some truth to Adrienne Rich’s line that every flag is a cry, not of pride, but of pain.

Or, rather, also, an attempt to cause pain in the other. It reminded me of the ending of “Jerusalem,” by Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai:

We have put up many flags,

They have put up many flags.

To make us think that they’re happy.

To make them think that we’re happy.

I’ve noticed fewer Irish flags in the past few years in nationalist areas—not because the people are less fervent about their commitment to a United Ireland, but because the community expresses its commitment in so many different ways—through colorful murals, through Irish-language on signs in the streets. It is a community feeling more confident about itself.

Which is why, perhaps, the Irish solidarity for Palestine isn’t really a cry of pain, but an echoing call. The Palestinian flag in Belfast as a visible sign of solidarity has become a flag that suggests two liberation struggles in one.

Of course, it’s not just Palestinian flags on display, but keffiyehs worn by former IRA volunteers like the green one sported by Peadar Whelan, tour guide on the Falls Road; t-shirts with Palestinian flags, like the one that sports the Free Derry gable, or the Free Derry gable itself, back in 2023 [all photos by the author, unless otherwise noted]:

Or, recently, the concert banners of Kneecap, the Irish language hip-hop group whose May 2025 trial in the UK on terrorism charges stems from their advocacy for Palestine (and holding up a Hezbollah flag during a concert).

All during our time in Ireland, we keep running into pro-Palestine murals and graffiti:

Belfast, Cathedral Quarter, May 19, 2025

West Belfast, May 22, 2025

Derry, May 24, 2025

The activism here isn’t just artistic, nor is it merely performative. A strong, voluble protest movement, led by the Belfast Palestine Solidarity Committee, presses for boycott, sanctions, and divestment of Israel. In fact, I’d seen posters for a Nakba Day rally in the center of Belfast on the very same day that we were due to walk on the Falls road for our tour of West Belfast. I was sorry that we couldn’t be in both places at once.

Poster for Nakba Day rally, May 17, 2025, courtesy Belfast Palestine Solidarity Committee

In West Belfast, where loyalist gangs burned down whole streets in August 1969, and where the British Army fought many battles with the Provisional IRA, the Irish-identified Republican struggle against British colonialism saw itself naturally allied with the Palestinian struggle for liberation from a state whose origins in British empire are undeniable.

They read like parallel, woven histories—the histories of Palestine and Ireland. The big player, of course, is the British empire and the story of colonialism. How a state comes to control another land and its people, sometimes slowly dispossessing the natives of their lands, sometimes laying waste to them, sometimes committing genocide. It goes back hundreds of years. It’s uncanny when you line them up.

Take Lord Arthur Balfour. In the 1880s, Balfour served as a British cabinet secretary for Ireland, opposing the Home Rule movement that would have allowed for Irish self-government. “Bloody Balfour” got his reputation from brutal crackdowns of protests. In 1917, he delivered what’s come to be known as the Balfour Declaration, which states that the British government “views with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object.”

Or take the year 1920. In 1920, the British government, under the Government of Ireland Act, partitioned Ireland, carving off six counties in the north and setting up the Protestant majority government of Northern Ireland. That Protestant majority were the descendants of settlers who had come in the early 1600s as part of the colonization of Ireland. In that same year, as part of the remapping of the Middle East after the end of World War I, the British established the Mandate of Palestine, administering control over the land, appointing Herbert Samuel, a leader of the Liberal Party and an ardent Zionist, as the first High Commissioner. Samuel, of course, had already been involved in Ireland. Acting as Home Secretary, he introduced martial law to Ireland after the 1916 Rising, and later recommended the hanging of Roger Casement, a British diplomat who was convicted of aiding the Irish rebels with a shipment of arms.

Ronald Storrs, who had been the Military Governor of Jerusalem from 1917 to 1920, would come to call the project that would become the state of Israel, “a little loyal Jewish Ulster in a sea of potentially hostile Arabism.”

The intensity of Irish expressions of solidarity in 2024 caused one pro-Israel commentator, Ben Cohen, to coin the term Paddystinian as a derisive epithet to counter the narrative.

Empires don’t need to win wars to maintain control. They only need enough assent from a portion of the governed to keep power. Sometimes, they work by creating the conditions of constant conflict—often by a “divide and rule” strategy, pitting local groups against each other—to justify military interventions and direct rule.

*

Ireland showed its longstanding, if well-earned, animus toward Britain by choosing to be neutral during the Second World War—despite the depravity of Nazism. Some, naturally, have wanted to suggest that Ireland is antisemitic, calling it the most anti-Israel country in Europe.

Others would say it’s just the most pro-Palestinian. Throughout the Irish Republic, from the Taoiseach to everyday people, Irish people express their solidarity with Palestinians with a sense of shared struggle against (British) imperialism.

The intensity of Irish expressions of solidarity in 2024 caused one pro-Israel commentator, Ben Cohen, to coin the term Paddystinian as a derisive epithet to counter the narrative, conflating the pejorative stereotype of the drunken Paddy with Palestine. Almost instantly, the movement flipped the script and adopted the term as a point of pride.

You can now buy tee shirts sporting different images of the Paddystinian movement.

*

While Irish solidarity with Palestine is an all-island phenomenon, it reaches its apex in the North, particularly in Belfast and Derry. After the partitions and wars of the mid-20th century in their respective countries, Irish nationalists in Northern Ireland and Palestinians in Israel (or just outside) were marginalized. The Irish Republican Army and the Palestine Liberation Organization, leading the armed struggles to liberate their countries, shared more than similar goals—and, in fact, they worked with each other beginning in the early 1970s, training together in Libya thanks to its dictator Muammar Gaddafi.

This mural was photographed in Belfast in 1982:

And this one, in Derry, May 25, 2025:

On an unseasonably sunny day on May 17th, 2025, we meet Padraig (who goes by Pod) Devenny, a former member of the IRA, and now a Coiste tour guide in the Falls community, at Divis Tower, to walk with him and learn more about the Irish Republican story. A lifetime ago, during the Troubles, he could not have imagined leading tours of his neighborhood. But after 1998, when the Good Friday Agreement was signed, a reality took hold. Peace changed everything.

As we walk down the road, he touches on the connections between the Irish struggle and the Palestinian one.

“We’ve heard a lot about hostages in the Middle East,” he says, “well, the British come into our homes, and took our fathers and brothers under the policy of internment.”

It’s unclear whether he’s referring to the Israeli hostages taken on October 7th, or the thousands of Palestinians arrested (some would say, abducted) without charge and held indefinitely. But clearly Pod knows the violence of the state intimately, beginning his tour by apologizing for his stutter, due to a brain injury sustained from a police beating.

We amble with him down the block on the Falls Road to the International Wall.

“The biggest weapon that any government has,” Pod says, “is not their armies, not their navies, not even their nuclear bombs. It’s the [journalistic] media.”

The International Wall is perhaps the most visited mural site in Belfast, and it’s one of the most artistic forms of media. Murals have long been a way for people from marginalized or oppressed communities to illustrate their own stories, communicate messages, honor their heroes, and remember the past as they wish to remember it. The Republican movement raised the mural into a sophisticated form of political art thanks to Pod’s brother, the artist Danny Devenny.

Over the years, I’ve seen the wall’s murals change, but they’ve always weaved together the Irish struggle with other liberation struggles across the world—in South Africa, Basque country, Cuba, Colombia, and, of course, Palestine. In early 2024, its murals became almost entirely devoted to the struggle for Palestinian liberation.

After Rana Hammoudeh, a Palestinian artist, visited the International Wall in 2023, she contacted Bill Rolston, the preeminent scholar of Belfast’s murals, proposing a collaboration where murals would be painted in both Ireland and Palestine. But life after October 7th, 2023 became more difficult for Palestinian artists. So Danny Devenny suggested that Palestinian artists send designs to be painted in Belfast.

“Do the murals ever receive hate or comments from people who walk by?” one of my students asks Pod. The students are often shocked by unapologetic solidarity for Palestine, having grown up in a society dominated by a pro-Israel narrative.

“No,” Pod says. “An American guy, last week, was annoyed that we were talking about Palestinian rights. He wanted to know why there were no murals to Israel… [it’s] because we don’t support Israel. We have a view on a conflict based on our history. If you want to see Israel, go to the other side of the wall [to the loyalist side.] We don’t accept what the media tells us.”

At the International Wall, moving from right to left, after a mural for Irish prisoners, comes the first Palestinian mural. It’s accompanied by a small image of a father carrying a child who has been wounded or killed. Next to it, a rectangular mural reads: Stop the Slaughter. Ceasefire now. At the base of the mural, surrounded by rubble, a boy and girl huddle together, the girl leaning on the boy, his arm wrapped around her. He stares directly at us, with a look that implicates, as if imploring or judging. The frame of the mural is of the Palestinian flag:

Threading the next few murals together is a painted red ribbon emblazoned with Refaat Alareer’s poem, “If I Must Die,” which went viral after his murder in November 2024. Alareer, a professor of literature at the Islamic University of Gaza, alludes to Claude McKay’s great poem of resistance, “If We Must Die,” written during the terrifying “Red Summer” pogroms of Black people in the US in 1919—another in a series of signs that, after World War I, a vicious reassertion of dominance was the order of the day.

“If I Must Die” works as Alareer’s last will and testament, since the poet had a premonition that Israel would kill him, and an invitation to hope against hope:

If I must die,

you must live

to tell my story

to sell my things

to buy a piece of cloth

and some strings,

(make it white with a long tail)

so that a child, somewhere in Gaza

while looking heaven in the eye

awaiting his dad who left in a blaze–

and bid no one farewell

not even to his flesh

not even to himself–

sees the kite, my kite you made, flying up above

and thinks for a moment an angel is there

bringing back love

If I must die

let it bring hope

let it be a tale

(translation by Sinan Antoon)

I’d read it earlier, but then saw the poem at the Case Western Reserve University encampment, named the Hind Oval Encampment, after five-year-old Hind Rajab, murdered by Israel in January 2024, struck by hundreds of bullets while hiding in her family’s car in Gaza City. In May 2024, I spent the day there, impressed by this visible sign of resistance and solidarity. Someone had installed the poem as a series of makeshift kites around the perimeter, alongside other posters of solidarity. Jewish Voice for Peace alongside Students for Justice in Palestine, made this encampment richly diverse. I witnessed a joyful Social Justice Seder, led by JVP members.

It was moving to see Alareer’s poem, markered with homemade lettering on white sheets, unfold around this new space, this liberated zone. The poem functioned as a talisman to these students, offering a vision of a possible future, where mutual aid and solidarity across difference told an alternative story to the one skewed by both corporate and rightwing media.

Back at the International Wall, we see that the second image depicts a seated woman in a Palestinian keffiyeh, preparing a meal over a fire, while her children look out from the tent where they live. Given the mass movement of populations from the north of Gaza, many thousands have been forced to relocate to temporary tents. This tent also hauntingly echoes the original tent cities created during the Nakba of 1948, when 750,000 Palestinians fled their homes and became refugees. Alareer’s poem also threads her into the weave.

We spend only a few moments in front of the International Wall before we continue heading down the Falls Road, to learn more about the Troubles.

It’s too much to take in all at once.

So I keep going back to those photos, trying to read them for all the stories that the Palestinian artists want to share with their Irish friends, and with us. I ask students to send me photos that I’d missed.

Seen from a distance, the murals seem almost beautiful, with their colors and images of children.

But looking closer, you notice the mural of prisoners on their knees, and a black-and-white one of killers standing over dead children.

At least three of the Palestinian artists, including Heba Zagout, have been killed by Israel since the start of the genocide. Zagout’s beautiful mural in particular looks more celebratory than dirgelike, and it made me wonder at how artists reframe reality:

On the one hand, the colors invite us into a scene of a city bedecked with both Muslim crescents and Christian crosses, alluding to the two religious communities of Palestinians. But those explosions in the sky may not be fireworks, but actual missiles and bombs. The destruction is either yet to come, or sometime in a distant past. On the other hand, it invites us to wonder if it’s possibly too pretty, too dissociated from the death happening in Gaza?

But isn’t it always all happening all at once? Beauty and ugliness all wound together, as they are on these murals, as they are even in Gaza during a genocide?

Further down, we see the image of a brown trench, lined with body after body in blue covering. Early in the Gaza genocide, there were so many people killed that individual burials were no longer possible, and traditional burial cloths had run out. So they had to dig trenches and use blue tarps instead.

Around the corner, the murals continue, with a long one that says, “Our Struggle Continues,” featuring Leila Khaled, the iconic hijacker and fighter for the Population Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and Charlie Hughes, an IRA martyr who was killed in 1971.

But it’s unfair to reduce Irish solidarity to an ideological or political alliance. This is where history meets lived experience, where history is not in the remote past, but located, sometimes, in nodes of trauma in bodies and psyches.

In “Why Ireland is One of Most Pro-Palestinian Nations in the World,” Lauren Frayer and Fatima Al-Kassab quote David Chambers (also known as the Blindboy),

When we [Irish people] see what happens in Palestine—people shot dead while waving white flags—that’s an immediate cultural memory. We saw that in the 1970s in Derry [during the Bloody Sunday massacre in 1972]. We can’t turn away from this. It’s our grandparents.

In the words of Frankie McNamara, creator of Meditations for an Anxious Mind videos, recently shared,

We look to Palestine, because we know empire when we see it, and when the elite try to paint your grief as graffiti and your resistance as barbarism, we remember how long Ireland took to dig up its own bodies.

It’s more than just the killing. It’s the trauma of people being expelled from their homes. People abused on the streets, imprisoned without trial. People treated like animals, or worse.

And people dying of starvation.

“It’s triggering for people, the images of people starving,” Ruairi, our tour guide and longtime friend in Derry, will say, when we visit him the following week.

Poor people know the intimate, badgering pangs of hunger, but in Ireland, the memory of the 1845-1848 Famine—the Great Hunger, when one million died from starvation and disease, and another million emigrated—still aches. You can find murals in Belfast calling the famine a genocide.

In the summer of 2025, I’m seeing images of Palestinians in Gaza starving every day. People shot and killed while lining up for aid from food trucks.

*

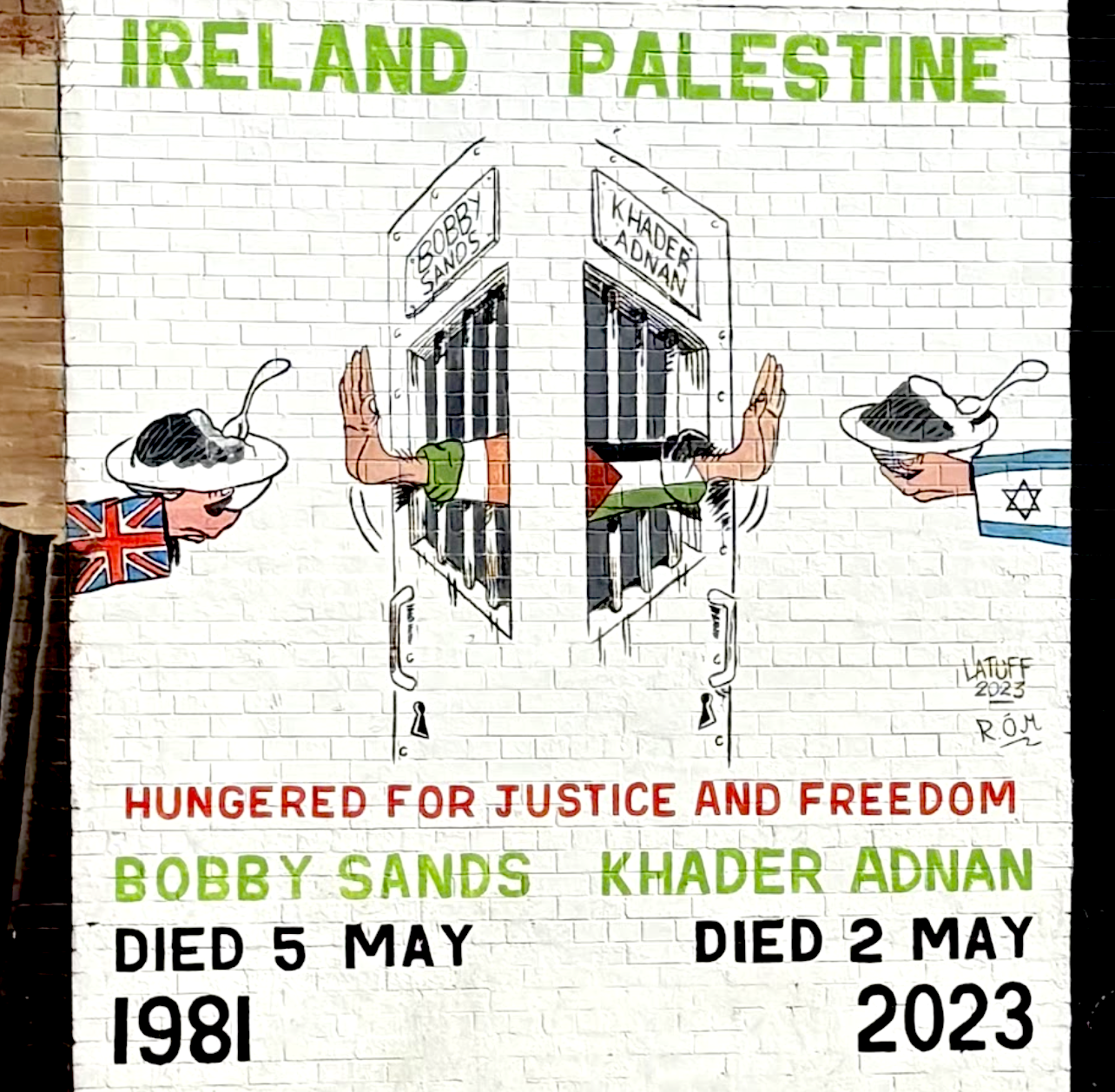

On the International Wall, one more mural catches my eye.

In 2017, I’d noticed references to Khader Adnan, a Palestinian hunger striker. I’d posted about it on Facebook—how 1,500 Palestinian prisoners were on hunger strike to improve conditions in the jail, calling for a telephone to communicate with their families, regular family visits, and improved medical treatment. Most of all, they wanted an end to Israel’s longstanding and interminable policy of detention without charge. This is what I’d written back in 2017:

I write this as many hundreds of Palestinian hunger strikers are in their second month of a strike protesting conditions in Israeli jails. The silence in the United States and Britain has been the rule, not the exception. Whenever I post on Palestine, there are few “likes.” People are afraid even to “like” something. It’s deemed controversial, too complicated, even antisemitic. While it can be controversial, and certainly is complicated, the final accusation is one that shuts down honest and open inquiry.

Anyone who has studied Jewish history and knows the history of antisemitism should be more interested in this situation, not less. My only wish is that we could explore more fully how to promote a just peace, and it isn’t by being silent and afraid. More engagement, more dialogue, more confrontation of our own complicity is what we need.

In a few short years, my plaintive, pleading tone would seem awkward and apologetic, compared to the confrontational calls on campuses for a free Palestine from the river to the sea, or Kneecap’s concert criticisms.

*

Bobby Sands, the iconic martyr of the Republican movement, who’d led and then died on hunger strike after 66 days back in 1981, had been part of a shift in strategy. While on hunger strike, he was put up for election for a UK assembly seat, and against all odds, won.

Prime Minister Thatcher refused to accede to the prisoners’ demands, even if that meant allowing an elected member of Parliament to die. But the worldwide attention made the Republican leadership rethink the possibility of a political strategy to gain Irish freedom, and the wheels toward a political solution began grinding slowly, agonizingly slowly, toward peace. A peace that Sands and nine other hunger strikers would never see.

Adnan also became a martyr, but without the international notoriety of Sands. An activist for the Palestinian Islamic Jihad, Adnan protested his constant detentions by engaging in a series of hunger strikes. In 2011, Adnan’s first hunger strike lasted 66 days, as if in homage to Sands. It’s unclear precisely how he survived that long. His second, in 2014, lasted 56 days. In 2023, his third hunger strike lasted 87 days, ending in his death.

The only place I’ve ever seen him honored is in Belfast.

In 2015, while visiting Northern Ireland’s parliament cafeteria, I was in line in front of Pat Sheehan, a former IRA hunger striker. During the strike that cost Sands his life, Sheehan fasted 55 days before the hunger strike was called off. Decades later, now a Member of the Legislative Assembly, Sheehan had gotten a hamburger and fries. The line was long, and clearly the man was hungry. He couldn’t stop eating his fries, and his buddies were making fun of him. He laughed sheepishly. It was poignant, an irony of history—how someone who’d fasted nearly to death now was being teased for chowing down on his fries while waiting in line to pay the cashier.

But how could they understand what it meant to be hungry?

So it wasn’t surprising to see Pat Sheehan speaking at the unveiling of the Palestinian murals on the International Wall.

In the background, just over Sheehan’s right shoulder, is the mural honoring the hunger strikers, Sands and Adnan.

*

Presbyterian minister and longtime director of 174 Trust, a community organization serving North Belfast, Reverend Bill Shaw grew up in the loyalist Sandy Row neighborhood of Belfast. The accepted narrative at home was a pro-Israeli one, where he would have heard about “dirty Arabs,” and Palestinians as “suicide bombers.”

Everything changed when he became a delegate for the Belfast Interface Project on a trip to Israel/Palestine in 2013. While in Sderot, an Israeli town that borders Gaza, the delegation met folks at an Israeli trauma center. Looking out over Gaza, Shaw wondered aloud about traumatized kids living there, and whether there was any cross-community collaboration. “The [Israeli] woman looked at me,” Shaw said, “as if I’d just farted.” He was surprised, since in Belfast, it had been common practice for people to do such work.

In Hebron, Shaw was astonished by the enforced separation between Palestinians and Israelis. “If you knew anyone who was skeptical about the evils of the occupation, take them to Hebron.” He saw how Palestinians were not allowed on their own street. He saw Israeli soldiers mocking an old Arab man with a pacemaker, who wanted them to turn off the security gate before he passed through. He had an Israeli sniper train his rifle on him.

They visited a Bedouin family whose house had been demolished three times by the IDF, whose lands were stinking due to the sewer runoff from an Israeli settlement above. When asked what they could do, the sheikh said, “We don’t want your money. We just want you to tell people what you saw.”

Later, at a checkpoint, Shaw had a close look at the separation wall, checking out the Banksy art. One graffito struck him in the heart. It read: “Now that you’ve seen this, you are responsible.”

Shaw came back a changed man and got involved in local organizations where he often found that he was the only Protestant. When he’d arrive, the other protesters would joke, “Here’s the Prod.” He’d joke back that he wanted to get a banner that read “Prods for Palestine,” but there was no one to hold the other end.

He helped write the Kairos Ireland document, a Christian-Palestinian solidarity organization, and went back to Bethlehem in 2018 for the Kairos conference. He also helped birth Christians4Palestine, calling out churches to move beyond praying for peace, to make statements of solidarity with the Palestinian people and to sign onto the Boycott, Sanctions, and Divestment (BDS) campaign.

But this work hasn’t come without a cost. In 2014, while posting on Facebook against Israel’s bombing of Gaza, Shaw received an official complaint lodged at Presbyterian headquarters. He wrote a five-page defense in response, concluding it, “having been and seen [the occupation], I can’t unsee what I saw. And having seen it, if I didn’t speak out, I wouldn’t be the person you employed to lead 174 Trust.” In the end, the board backed him.

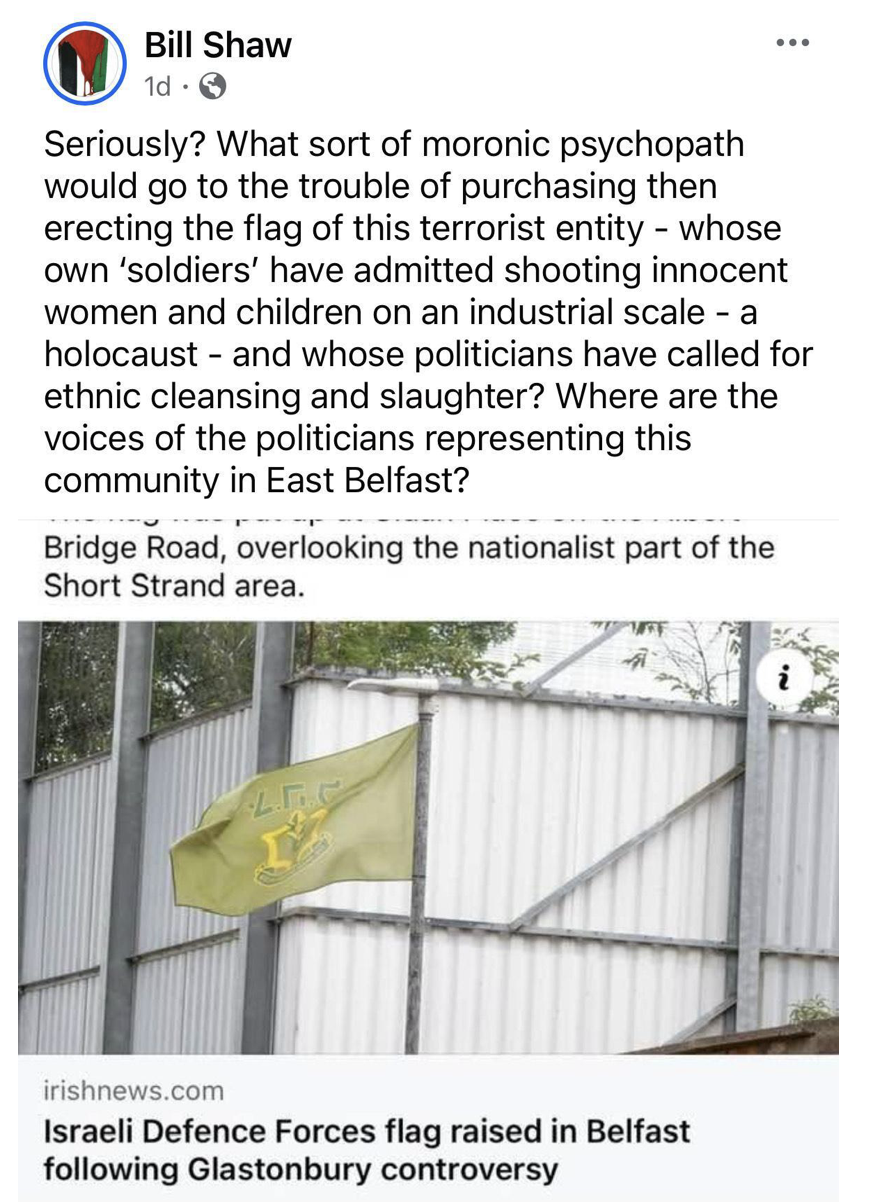

He posts daily content on Facebook on Palestine, in his words, “for my mental health.” On the day of our conversation on Zoom, he’d just posted about an IDF flag that had recently been flown in a loyalist area, right next to a nationalist enclave. He was furious, calling out his own community.

I told Shaw on Zoom that I was writing a piece about the “Paddystinians” of Belfast, and he leaned over and produced a “Proud Paddystinian” button for the camera.

He keeps posting on Facebook, inspired by Palestinian Lutheran minister Munther Isaac, whose words he heard in Bethlehem in 2024: “Keep standing up, keep speaking out.”

It’s true that the Irish alone won’t be able to stop the genocide. And even if it stopped tomorrow, what has happened is already too much to bear. Its terrible cost will echo down through the generations—for Palestinians, for Israelis, for all of us whose countries silently watched or actively fed the machinery of genocide. At least, Shaw says, Palestinians will know that Irish people saw their struggle for freedom and justice as inextricable from their own. That they stood up. That they kept speaking out.

Philip Metres

Philip Metres is the author of Ochre & Rust: New Selected Poems of Sergey Gandlevsky (2023), Shrapnel Maps (2020), The Sound of Listening (2018), Sand Opera (2015), and other books. His work has garnered fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, Lannan Foundation, NEA, and the Ohio Arts Council. He has received the Hunt Prize, the Adrienne Rich Award, three Arab American Book Awards, the Lyric Poetry Prize, and the Cleveland Arts Prize. He is professor of English and director of the Peace, Justice, and Human Rights program at John Carroll University, and Core Faculty at Vermont College of Fine Arts.