The Overlooked Story of Two Women in the Southampton Slave Rebellion

Vanessa M. Holden Offers a Different Perspective on the 1831 Uprising

The heat of a Southside August was kind to cotton and nothing else. The only other living things that looked forward to the heat were preachers; it was sitting-in season for the white folk who could travel to revivals. They would wait on the Lord and wait for the king, king cotton, to burst open, make his presence known, and demand more tribute in sweat and scars. The white fluffy wealth was all over the county. Some big men had vast fields, while many others had patches here and there. In the heat and the foggy haze of swampy humidity, the cotton no longer needed chopping. It just needed sun and water and time. Then the hardest season would come in a wave of bursting bolls. The cotton would open up and the hands would sweep it up and the gins would clean it up and the hands would mote it out and card it. But in August, the cotton would bide time and mature and the hands would spend less time in the fields and more time occupied elsewhere.

For women like Charlotte, there was never an end to work, no matter what season it was. The cotton was just one thing growing. In the summer of 1831, for example, her new enslaver, Lavinia Francis, for example was close to welcoming her first child. Lavinia was only 18 at the time. Her young husband, Nathaniel Francis, brought his wife to his childhood homeplace from Northampton County, North Carolina, just over the border from Southampton County, Virginia. Lavinia took over as mistress from Nathaniel’s mother, who still lived on the place. With the new woman of the house came another new woman. Ester, an enslaved woman, came along from North Carolina as a wedding gift like a trunk or a trousseau. The heat could not have been easy on Lavinia in her condition. She’d grown up in the heat of the region just across the border, but that summer she was sweating for two.

The Francis family perhaps later recalled rebels arriving on their place in the morning of August 22, 1831, on the heels of a young boy they knew from the farm of neighboring kin, but the truth was that rebels had arrived much earlier than that. Francis’s enslaved laborers, Sam and Will, were both original conspirators with Nat Turner, who, along with a small group of others, had plotted at least since that spring to foment rebellion in the neighborhood. Will had been in the Francis holdings since the time of Nathaniel’s father, Samuel Francis. The enslaved man Sam had arrived on the farm in the early 1820s. As one historian of the rebellion points out, “The holdings of Nathaniel and his sister together would produce four of the seven original insurgents, including the leader, his chief lieutenant, and the ‘executioner.’” Ultimately, six men and boys from Nathaniel Francis’s place, none of whom were recent arrivals to his holdings, traveled the county with the rebels in August 1831.

What happened in the Francis kitchen was as much a part of the Southampton Rebellion as Nat Turner’s initial Cabin Pond meeting and the killing of Nathaniel Francis’s kin in his front yard.

The happenings around and outside the Francis homeplace have received ample attention from historians. When the rebels arrived on the farm, they murdered the Francis’s overseer and their two young, orphaned nephews. They searched for Lavinia, Nathaniel, and Nathaniel’s mother, and when they could not find them, they went on to a neighboring farm. The rebellion did not end at the Francis farm when the men and boys went on to the next farm. Charlotte and Ester, who remained behind, set to work preparing food for the men to return to and began fighting over their Lavinia’s belongings.

Lavinia Francis was not dead. She’d passed out from the heat in an attic cubbyhole where a person enslaved by the extended Francis family had hidden her. When she woke up, she made her way to the kitchen behind the house, where she could hear Charlotte and Ester fighting. The three women regarded each other and the following moments moved quickly. Charlotte grabbed a handy knife and lunged at Lavinia. Ester stepped between them and held off Charlotte, who just missed dispatching their enslaver. Lavinia grabbed a nearby wheel of cheese and fled to the woods. In the space of a few hours, Lavinia Francis had escaped death twice; once at the hands of enslaved men and once at the other end of an enslaved woman’s kitchen knife.

Ester and Charlotte’s participation in the Southampton Rebellion was distinctly different from that of their male counterparts, who were elsewhere in the county by the time Lavinia Francis came to. Past histories of the Southampton Rebellion regard Ester and Charlotte’s story as anomalous and their actions as spontaneous. However, their motives were not different from those of male rebels. The two women acted no more out of personal resentment and frustration than the men for whom they cooked dinner. What happened in the Francis kitchen was as much a part of the Southampton Rebellion as Nat Turner’s initial Cabin Pond meeting and the killing of Nathaniel Francis’s kin in his front yard. The future rebels had lived on the place long before August of 1831. Including the enslaved women who lived on the farm in that category means that some rebels never really left.

However, their rebellion happened within the context of the Francis farm’s specific geographies. The farm’s kitchen was the site of significant domestic labor and a space where the Francises may have housed enslaved people. It was both intimate space and a thoroughfare. Within individual households and on individual farms and plantations, whites reproduced and curated the same geographies of surveillance and control that the broader Virginian society maintained. Law and custom dictated that enslavers were the architects of control in intimate spaces, sites of domestic labor, spaces where enslaved people processed each season’s yield, and the fields. Enslaved women’s gendered labor forced them to navigate each type of space on small and medium-sized plantations and farms. The Francis kitchen was one such space, and Ester and Charlotte’s confrontation with Lavinia Francis is one example of two geographies intersecting.

__________________________________

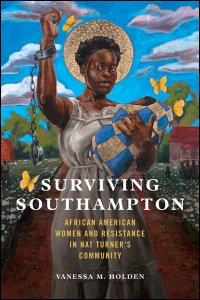

From Surviving Southampton: African American Women and Resistance in Nat Turner’s Community by Vanessa M. Holden. Copyright 2021 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. Used with permission of the University of Illinois Press.

Vanessa M. Holden

Vanessa M. Holden is an assistant professor of history at the University of Kentucky.