I.

Here’s a Truck Stop Instead of Saint Peter’s

Bedridden from blistering, hallucinatory fevers in Moscow, 1992, I first listened to R.E.M.’s “Man on the Moon” only half on this earth. I was doing a year-long fellowship in Russia studying contemporary Russian poetry and its relationship to historical change, translating and interviewing poets and trying to get my head around this massive, elusive, obdurate society. Russia evaded my understanding, pummeling me with its inhumane architecture and weather and indifferent crowds. I was stunned as much by the gorgeous and forbidding iconostases of the innumerable churches I’d entered, hoping for respite, as I was by the wrecked beggars who always seemed to stand guard outside, testing the limits of my mind and heart.

In my rented room, with some unnamed illness, my headphones on, I listened to Automatic for the People nearly straight through, playing track ten, “Man on the Moon,” more than a few times in a row. Though the song was clearly about Andy Kaufman and his comical way of bending reality, I wasn’t sure how it connected to the chorus, “If you believed they put a man on the moon /…/ Then nothing is cool.” I’d later learn that Kaufman was believed to have faked not only his wrestling matches but also his own death. The lines from the bridge struck me with the most force:

Here’s a little agit for the never-believer

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah

Here’s a little ghost for the offering

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah

Here’s a truck stop instead of Saint Peter’s

In those lines I saw a vision of what I kept stumbling across in poetry—the idea that something as vulgar as a truck stop could be site of beauty, truth, and God. That’s what Russia also kept teaching me—that if there were a God, God was as much with the blind man at the open mouth of the Pushkin Square metro, holding his sign asking for bread, as at Sergiyev Posad’s holy cathedral and its ornate iconography.

But probably it was that that blind man—the raw truth and need of him—fleshed forth a Spirit that I could neither countenance nor look away from.

II.

Is Nothing Sacred?

“Is nothing sacred?!” my mother would gasp, exasperated at the latest torrent of profanity or unashamed self-display on television or social media. Over the years, I’ve seen how, for my parents, the world seemed suddenly full of what they saw as coarseness, vulgarity, and profanity. Profane, from the Latin, meaning “that which is outside the temple.”

It is strange to grow old. In the modern world, that change seems to exile the aging, casting them out of a familiar world into an unsteady landscape where the old rules have evaporated. For my parents’ generation, growing up Catholic in a time when sex was a hidden thing, when few cursed and everyone dressed to impress, the world they encounter today must seem like a Babylon.

I confess I don’t understand precisely what the sacred means. Or rather, I want to resist it, as Michael Stipe, lyricist of R.E.M, resisted it in offering us a truck stop instead of Saint Peter’s. My younger brother, protesting going to Mass, asserted that he found God in the woods, not in church. Who’s to say where we encounter God, where we meet the line that separates the earthly and the divine?

III.

Set Apart (Nigh or at Hand?): Or, Transcendence versus Immanence

The notion of the sacred is as close to what we understand as the essence and origin of religion—that there is a space of divinity that is marked off, set apart. The word sacred dates from the fourteenth century, meaning something “hallowed, consecrated, or made holy by association with divinity or divine things or by religious ceremony or sanction,” and comes from the Latin sacrare, “to make sacred, consecrate; hold sacred; immortalize; set apart, dedicate.” It is this notion of being set apart that is contained in the Latin word for priest, sacerdos—one who is set apart. The same is true of the Greek and Hebrew terms (hagios and kadosh)—except that the kadosh includes all manner of practices and objects that are godly (kosher relations, food, et cetera).

According to Cunningham and Kelsay in The Sacred Quest, “Religion signifies those ways of viewing the world which refer to (1) a notion of sacred reality (2) made manifest in human experience (3) in such a way as to produce long-lasting ways of thinking, feeling, and acting (4) with respect to problems of ordering and understanding existence.” There is another world, religion seems to say.

But where, precisely, is it? Is it in the sky (heavens), or among us (or even within us)? Both? Or, the agnostic in me wonders, neither? Translations of Jesus’s words seem to vacillate between suggesting the kingdom is both “nigh” and “at hand,” here and also shortly to come. In religious terms, whether we encounter the divine through transcendence or immanence has been a living question. Rudolf Otto’s The Idea of the Holy (1917) proposes that religion should not be reduced to rationality, making an argument for nonrational apperception. Otto’s notion of the numinous—what he defines as “non-rational, non-sensory experience or feeling whose primary and immediate object is outside the self”—proposes that some experience of God is not grounded in the senses but is nonetheless felt. In one poetic passage, Otto writes that we are dealing with something for which there is only one appropriate expression, mysterium tremendum [a mystery that repels]…. The feeling of it may at times come sweeping like a gentle tide pervading the mind with a tranquil mood of deepest worship. It may pass over into a more set and lasting attitude of the soul, continuing, as it were, thrillingly vibrant and resonant, until at last it dies away and the soul resumes its “profane,” non-religious mood of everyday experience. … It has its crude, barbaric antecedents and early manifestations, and again it may be developed into something beautiful and pure and glorious. It may become the hushed, trembling, and speechless humility of the creature in the presence of—whom or what? In the presence of that which is a Mystery inexpressible and above all creatures.

Here Otto sides with the mystic sensibility—the belief that the transcendent unknowability of God nonetheless sometimes comes into our awareness. In many respects, Otto’s sensibility is deeply Protestant, a theological resistance to an all-too- human fleshy Catholicism (and its enormous corruption), an argument that Johann Huizinga makes in The Waning of the Middle Ages. In Kenneth Woodward’s words, “the Reformation was a reaction that put God and the things of God at greater distance from this fallen human world, thus allowing more space for human freedom and folly, and a rejection of images and all other visual manifestations of heavenly presences in favor the preached word.”

Yet any distinction—like David Tracy’s, between the Protestant dialogical imagination, which emphasizes God’s absence and unknowability, and the Catholic analogical imagination, which emphasizes God’s presence in the things of the world— blurs when we begin to consider particulars. (Ultimately, both approaches are present in Catholicism and Protestantism, as well as in other religions across the world.)

Growing up in the Catholic Church, I could not reconcile the contradictions. It kept me up late at night, in terror of my body’s sexual desires, which seemed to rebel against my will. The church said that ours was a faith seeking reason, but didn’t seem to truck with questioning of authority. It said we were all God’s creation, and that we were good, but also that our bodies were perilous sites of sin and even the thought of sin was a sin. Not only was the kingdom of heaven within us but also the fiery pits of hell. It was a heck of a lot to hoist on one’s young shoulders. As I grew, I pined for a faith that was sensuous, unafraid of the senses, that might unwrite the “hatred of the world” codes that still were part of the incense of the church.

IV.

Poets and (versus?) the Sacred

In Catholic Foundations, our senior theology class at Loyola Academy, the nattily dressed Mr. Rattigan hoisted the Bible in his meaty hand, saying, it’s just a book, and then tossing it into the metal trash can in the corner of the room. The thunk was majestic. It’s just a book, he intoned again, looking at us with a shrug, waiting for a protest that didn’t come. Then he took a crucifix. What’s this? A symbol. Thunk. It was just so punk rock. (Good old Patty Ratt, someone wrote on his obituary page.) He knew the difference between a symbol and a real presence.

I found the kind of faith I craved in modern poetry, which seemed, in the debate between the transcendent and immanent, to vote with the earthly. As the French poet Paul Éluard was thought to have written, “There is another world, and it is in this one.” Or, as Denise Levertov writes, “The world is / not with us enough

/ O taste and see.” The poetic daughter of William Carlos Williams (no ideas but in things!), Levertov’s immanence was religious in implication (no God but in this world!). What a relief, to know that this world—whatever its difficulties—was also paradise, in which we both hunger and can pluck the fruit.

Across cultures and time, poets have had a long-standing wrestle with religion. In the Venn diagram of language, religion, after all, has a healthy overlap with poetry. “When we look at religious language,” Cunningham and Kelsey propose, “we find something very close to poetry: Believers (and poets) use ordinary words, yet they want to convey a sense of something that they consider larger, more profound.”

Yet the tension between the modern poet and the religious temperament comes from the orientation toward mystery: the modern poet often stays on the plane of questions, the plane of complex experience, while religions, by their very nature, offer a fully formed answer, a worldview, in the shape of faith. It might be possible to say of religion, tongue firmly planted in cheek, what Emerson said of language in his essay “The Poet”—that it is “fossil poetry.”

That isn’t to say that poets don’t have worldviews or that religions don’t understand mystery. But if (again Emerson) “the quality of the imagination is to flow, and not to freeze,” the codification necessary to make a durable religion is in tension with a durable poetic impulse, which is to honor uncertainty and flux.

V.

God in All Things (?!)

Poetry (and in poetry, I include the lyrics that I studied like a monk studying Scripture) grounded me in the earthly, even as my soul keep darting to the skies. During an eight-day Spiritual Exercises silent retreat as a freshman in college, I learned to see how the simultaneous impossibles—an intimate God and a distant God, the world and the otherworld, my body and my soul—were connected. I’d begun to wonder, if I really did believe in God, whether I should cast aside my poetry, whether poetry wasn’t an exercise in ego and vanity.

It was there that I read Saint Ignatius of Loyola’s First Principle and Foundation of the Spiritual Exercises and reflected on its meaning. In David Fleming’s paraphrase, Ignatius invites us to contemplate the goodness of creation and the love of God: “All the things in this world are also created because of God’s love and they become a context of gifts, presented to us so that we can know God more easily and make a return of love more readily.”

What if I could see creation itself, and ourselves in particular, made in the image of God, as good—even as sacred? The Ignatian notion that our very lives could be a text in which we read the movement of the Spirit excited and unnerved me. Still does. The Ignatian idea of “God in all things” was alternately dizzying and consoling. How could God be present in all this hugger-mugger, the chaos of every day?

Could anything at all be that door, that threshold, between—but between what? I want to say, without hard evidence, speaking from the gut: between our inmost being and the Being of Beings, or Being itself. Where the circle of our self-enclosure opens into that which we all, in the end, become. What if places, occasions, encounters could become the threshold between the earthly and the infinite? The Irish have a term for the geography of the spirit: “thin places.”

The sacred, perhaps, is a recognition of what Gerard Manley Hopkins observed, ecstatically, as that which is “charged with the grandeur of God”—that pulsing beauty that we, at moments, glimpse, gaze upon, or are overcome by. Everything from dappled things to sublime craggy mountains or surging seas.

But everything?—the skeptic in me wondered. Pornography? The meaningless suffering of children? Murder? Covid-19? War? Like those platitudes about maintaining the attitude of gratitude, the God in All Things concept ushers forth its own kind of terror. Why can’t we just also despair about—or have some mercy to breathe in— the absence of God? Every religious or spiritual poet must confront the presence of evil, or whatever we mean when we say evil—suffering caused by humans that could otherwise be avoided, whether it’s a singular act of violence or systemic racism.

Sometimes the absence of God might be a reprieve. The filmmaker Chris Marker once said, “I’ve been around the world several times, and only banality still interests me.” Can the banal and profane also be themselves, or must God be rolling about everywhere, bowling us over like candlepins?

In his Penguin Book of Spiritual Verse (2022), Kaveh Akbar proposes that sacred poetry, from his experience as a Muslim, is “earnest, musical language meant to thin the partition between a person and the divine, whether that divine is God or the universe or desire or land or family or justice or community or sex or joy or.” It’s in that list that we feel our postmodern awareness that whatever idea of God we might have, there are others out there—other people finding their way, and other gods as well. There is more to heaven than is dreamt of in our theology. I don’t have answers to these unfolding and perhaps ultimately obdurate questions. And that is why I go to poetry, as a reader and as a writer.

And wherever I look, I see poets—whatever their religious background—struggling with the same unanswerables, with the limits of our received notions of earth and spirit and their relations. The so-called faiths of the Book—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—come from the radical notion of a person-like God—a God like and unlike us, figured most often as Father, but sometimes as Lover, sometimes as Child, et cetera. How radical to employ the metaphors of our most intimate human relationships to talk about this relationship with something beyond our conception. That sense of a God whom we could apprehend as filial, as familial, meant that we were not created by a clockmaker, but attended to, down to the hairs on our head (Luke 12:7). (Of course, such figurings cause us to pause over the Mother Goddesses and pagan practices that these faiths often attacked, consumed, and erased.)

Against the backdrop of grief, what sort of God or gods can one believe in?The Hebrew poets and prophets capture so keenly the human roil of emotions about the divine—from abyssal distance to warm tenderness. Consider Isaiah 49:16: “Behold, I have inscribed you on the palm of my hand.” That notion of God is so different from the whirlwind unknowable God that Job encounters in the desert of his suffering. Consider the work of Kaveh Akbar and Mohja Kahf, or Erika Meitner and Yehoshua November, grounded in and sometimes wrestling against their Muslim and Jewish religious upbringings, and you will see far more in common than otherwise. A clearly Protestant poet like Christian Wiman, who struggles most fiercely against an absent God, has written such beautiful poems, like “From a Window,” about the beauty and presence of God as well. A Catholic poet like Angela Alaimo O’Donnell sings the feast of the human, but also its famine, in a poem called “Feast & Famine”:

Me, with my moonface and my thinning hair,

these coca-cola lenses that let me see

the mighty world and all that’s in it.

There is so much sorrow, so much beauty

Which is to say, I look to poets not to confirm my ideas of the world and of God but to be shaken awake by their vision, which invariably touches on the sheer mystery of existence—whether it’s because of the question of death or the question of how to live in (and sing) a world that has violently oppressed oneself and one’s people. These are the questions that attend the recent work of Victoria Chang and Yusef Komunyakaa.

VI.

I Am Still Angry with God and All the Patterns We’re Forced to Follow

In the last few years, Victoria Chang has become the poet laureate of grief. With Obit (2020); Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief (2021); and now The Trees Witness Everything (2022), Chang confronted the losses of her father (whose stroke left him utterly changed in 2009) and her mother (who died due to pulmonary fibrosis in 2015) and became an informal companion to many readers as we collectively face the wider grief of the Covid pandemic.

Not surprisingly, Chang’s confrontation with death shakes the foundations of her worldview and her ideas of God. Grief, after all, is the soul’s honoring of the beloved, who is sacred to us. What has come between us, we might wonder, but an indifferent God? Chang grew up going to a Presbyterian church, where her family found community among other Chinese and Taiwanese churchgoers. She shared with me that her mother “would often say, ‘lao tien yeh,’ which means God, and add, ‘is watching,’ or ‘don’t say that because lao tien yeh will hear you.’ She also believed in the concept of fate and often talked about ‘ming’ or fate—she would often say, ‘that is just your ming,’ meaning, ‘too bad, that’s what your fate is.’” There is, of course, a tension between a theology of a living, watching God and a universe where we must face our fate. And that tension is alive in The Trees Witness Everything. If in Obit, as one interviewer noted, there was no mention of God, the word God appears a number of times in The Trees.

Against the backdrop of grief, what sort of God or gods can one believe in? Her poems in The Trees, mostly following the strict syllabic structure of the Japanese waka (five lines of five, seven, five, seven, and seven syllables), feel restrained, compressed, and bounded. There is a double honoring happening here, as she’s taken the titles of her poems from the late W.S. Merwin’s catalog of titles—another honoring of an elder recently departed. Following a strict form with predetermined titles offers a poet a sense of boundary and containment, but form can also feel like a jacket one size too small, in which it’s hard to move one’s limbs.

I was supposed to

return to the fields daily.

I haven’t been there

since birth. On some nights, I smell

smoke that I think is

God calling me… (from “Green Fields”)

The fields suggest some open space, a pastoral breadth that suggests paradise and which she associates with her childhood, but there, Chang smells smoke and only finds a clothesline with “half a life / clipped on it.” Midlife, as Robert Frost has explored in “The Oven Bird,” is often the question of “what to make of a diminished thing.” As we face the limits of our own bodies and the deaths of our beloved elders, we can feel hemmed in, and like Job we cry out in protest, in anguish. Perhaps the strict waka is the ideal form for Chang, as she struggles against the limits of a life, against the enormity of death and the distance of God.

Or even the nonexistence of God. Such losses throw into question whether we believe at all in a divinity who cares, who can intervene in the affairs of mere humans. All around us, we have signs of that indifference.

The Gods

The fact that leaves can’t

be put back on trees makes me

think that you do not exist

What do we make of a material world where entropy rules, where death is our inevitable end? Where does the Christian idea of a loving God fit in? It often doesn’t. It enrages us, as it does Chang.

I am still angry

with God and all the patterns

we’re forced to follow.

I still can’t look beyond death… (from “The Wild”)

These tight wakas, like our fate, bridle us, raise our rage, make our hearts beat against their impossible, immovable cages.

And yet, in a poem toward the end of her collection, Chang offers some small consolation.

For the Anniversary of My Death

So many people

don’t yet know they are not here.

I am still here in the rain,

waiting to be called.

The water is still bluish,

God is still the minute hand.

Death is a strange thing. The person who was once so alive is now gone, and yet they live, somehow, in us. We are the urns where they rest. Our grief tears us from the present, exiles us in the living past. We wait to be called.

“For the Anniversary of My Death” vibrates with the uncanny boundaries between life and death—the way some are living dead, and some are dead still living. The final line of the poem can be read in different ways. Is God the “minute hand” of a clock, present in each moment, slowly ticking forward? Or is God a “minute” or small hand, whose reach and grasp is small but “still” there. I recall, in a Russian church outside Moscow, a sculpture of Jesus with short arms, and it struck me with such force—that this is, so often, in our grief and suffering, how we see God. The silent God. The moved but unmoving God. The God of Tolstoy’s story “God Sees the Truth but Waits.”

VII.

Nothing Goes to Heaven without Going through You First

If Victoria Chang’s recent poetry aptly demonstrates how grief work shakes the foundations of the idea of God and the recompense of afterlife, Yusef Komunyakaa’s Everyday Mojo Songs of Earth (2022), a selection of poems from the last twenty years, illuminates a poet’s tenacious urge to call forth spirits and hold on to song in the face of dehumanization, cruelty, and war. The title itself—like so many Komunyakaa titles (Neon Vernacular, Talking Dirty to the Gods, Chameleon Couch)—is paradoxical. It’s an everyday workingman’s blues, yet is also marked by a magic (mojo, from the Creole meaning “magic”) that makes it possible to get over. The “of earth” signals his immanentist leanings. Komunyakaa is a sensual poet, a poet of earthly and earthy matters. In one interview, he observes the blurred lines between God talk and blues song: “We talk about the sacred and profane within the context of the blues as well, because often on the weekdays and Sunday some of these blues singers were very connected to the church. Saturday night was a different thing. It was a place of revision, but also it was a place of confrontation.” For much of his career, Komunyakaa has been a poet of careening Saturday nights, seeking structures and cadences of freedom, as Saturday bleeds into Sunday.

In fact, Komunyakaa’s first readerly experience, as a child, was the Bible, which he read twice through, noting that “the hypnotic biblical cadence brought me close to the texture of language.”

Despite the Bible’s ongoing influence—it still figures significantly in his repertoire of allusions—Komunyakaa is a roving poet whose mojo bag is stuffed with ingredients from nearly every continent and civilization.

Yet in a recent poem, the plaintive “A Prayer,” he shows the primal longing for home, offers up a petition as he witnesses a man dying in an airport café, as people stream around him on their phones:

Great Ooga-Booga, in your golden pavilion

beside the dung heap, please

don’t let me die in a public place.

…

Let me go to my fishing hole

an hour before the sun sinks

into the deep woods, or let me swing

on the front porch, higher & higher

till I’m walking on the ceiling.

That Komunyakaa has addressed the divine as “Ooga-Booga,” a term of uncertain origin redolent of minstrel performances, offers a level of ironic distance to what is a haunting poem of the fear of dying alone, anonymous, far from home. This is a poet who knows he’s slowly traveling to the unending night, the Saturday that may not turn to Sunday.

To reduce Komunyakaa to a religious poet is to miss his full-armed embrace of the earthly. But to pretend that his love song for the earth does not have another register is to miss his lifelong wrestle with those biblical stories and cadences that first woke him into poetry.Throughout his work, Komunyakaa proves his faith in the earthly. Two poems that I continue to return to are “Venus of Willendorf” and “Ode to the Maggot” from Talking Dirty to the Gods. Both give homage to something that’s small that packs big magic. Komunyakaa describes the legendary “Venus” as “big as a man’s fist / Big as a black pepper shaker / Filled with gris-gris dust.” She’s not a distant, ethereal spirit, but “earthy & egg-shaped,” a figure whose beauty “forces us to look / At the ground.” The poet ends, “In her big smallness / She makes us kneel.” While he’s not “talking dirty,” the poet does hearken to the flesh-centered theology of Baby Suggs in Toni Morrison’s Beloved, who calls upon the formerly enslaved to love their flesh, to reclaim their bodies from the brutality of ownership: “In this here place, we flesh; flesh that weeps, laughs; flesh that dances on bare feet in grass. Love it. Love it hard. Yonder they do not love your flesh.”

Descending even further into the earth, “Ode to the Maggot” praises a very unlikely creature, calling it “Brother of the blowfly / & godhead,” that works its own dirty magic. The poem ends:

Ontological & lustrous,

You cast spells on beggars & kings

Behind the stone door of Caesar’s tomb

Or split trench in a field of ragweed.

No decree or creed can outlaw you

As you take every living thing apart. Little

Master of earth, no one gets to heaven

Without going through you first.

This ode kneels down to examine—but not to dissect—the maggot, this gateway between death and life, animal and god. I love those final lines: the slant rhyme of “earth” and “first,” the forceful enjambment that postpones the attainability of heaven, and the journey of each of us through the maggot’s body. It is funny and poignant, unflinchingly considering our earthly end.

In a late poem, “Ecstatic,” Komunyakaa departs from his immanent mojo singing to explore the desire for transcendence, mashing together Hafiz’s image of a brawling God and Donne’s longing that his heart be beaten open:

Joy, use me like a whore.

Turn me inside out like Donne

Desired God to do with him.

…Please, good God,

Put everything into your swing.

It’s a shocking poem, calling for God (Joy) to beat him until he achieves ecstasy. All the more shocking given how, in institutional religions, the abuse of the powerful has cratered people’s trust in churches. Yet there’s something so bracingly honest about the speaker’s longing. Sometimes we long to slough off our bodies and all their pains. This is the peace of death, one that the poet of “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” has yet to understand, still in the throes of grief. “Ecstasy” reminds me, weirdly, of T.S. Eliot’s admission that “only those who have personality and emotions know what it means to want to escape from these things.”

To reduce Komunyakaa to a religious poet is to miss his full-armed embrace of the earthly. But to pretend that his love song for the earth does not have another register is to miss his lifelong wrestle with those biblical stories and cadences that first woke him into poetry.

VIII.

Open Temples

In the end, poets, like their theologian kin, find recourse in both the immanent and transcendent modes. Spirit, the breath, after all, is both in us and outside of us, moving through us, keeping us alive until we breathe our last. We are its open temples. Yeats describes it well in “Vacillation,” a poem pitched between the claims of the heart and the call of the soul. There, he recalls a moment past midlife, sitting alone in a bustling London café, looking out at the street when some sudden joy overcame him:

My fiftieth year had come and gone,

I sat, a solitary man,

In a crowded London shop,

An open book and empty cup

On the marble table-top.

While on the shop and street I gazed

My body of a sudden blazed;

And twenty minutes more or less

It seemed, so great my happiness,

That I was blessed and could bless.

Sometimes, in those fugitive moments when I’m struck by a sudden flash of such grace, I don’t care if it’s a trick of endorphins or Otto’s non-sensory sense or the Ignatian God in all things. In those moments, something in me thrills, transports me beyond myself and my petty suffering. Riven by feeling, buoyed by delight, I sense both my utter smallness and the total immensity of existence. We are not magnificent, as Bon Iver sings in “Holocene,” but at times, perhaps, we are the shape of such grace.

___________________________________

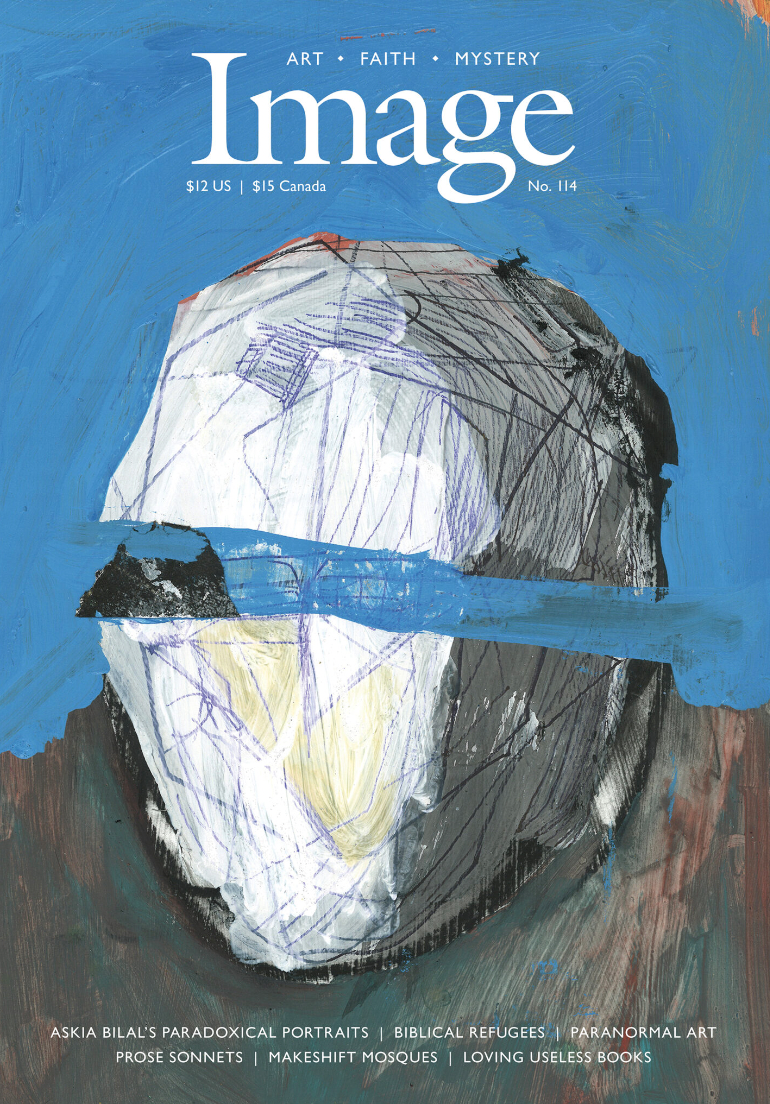

This essay was originally published in Issue 114 of Image.