The child held on to Clem’s hand throughout the bus ride. There were lots of stops and the brakes were jerky, and after an hour she murmured, “I feel sick.” Back at Sinclair House it would have been a risky admission, but Clem didn’t seem cross at all. “Nearly there,” he said, elbowing her as he rummaged in his coat pocket. “See if you can’t hold on another ten minutes.” She nodded as Clem blew the fuzz off a mint imperial and pressed it into her mitten.

She was glad to have the new mittens when they got off the bus. Clem didn’t wear gloves, but his hands had the impervious look of old leather, so perhaps they repelled the cold by themselves. Apparently, Lorna had knitted the mittens specially for her and they’d bought the coat brand-new, last Saturday, from the big department store in town. It was navy blue with a square collar like a sailor’s, and it was a bit tight at her shoulders, but thank goodness she hadn’t gotten sick on it. She shivered as the bus pulled away, and Clem said, “Warm enough?” She nodded and he stooped to straighten her scarf, which had gotten tangled with the strap on her gas-mask box.

The child hadn’t been outside without her gas mask for months; not since the start of the war. Everyone was supposed to carry one, in case the Nazis dropped poison-gas bombs—the government had said so. At the orphanage you got a proper telling off if you went anywhere without one, so Virginia was troubled—and impressed—to see that Clem had left his at home.

The bus had dropped them by an old church with a tower like a stubby finger pointing at the sky and a sign that said St. Dunstan’s, Tollbury Point. The little girl turned slowly, taking in the bare trees and the whitewashed cottages, and tried to guess which one was her new home. Most of the cottages already had their blackout curtains drawn; one risked an uncurtained window and an open fire, and looked the nicest in the raw dusk. But Clem adjusted his hold on her slippery mitten, picked up the suitcase, and led her away, down a different road.

Beyond the village, the silence was immense. At Sinclair House there’d been no such thing as silence, even when Matron ordered it; there’d been too many children and too many echoes in the tall, bare rooms.

Clem didn’t seem one for talking. When they were trudging down the drive, away from Sinclair House, he’d said, “Best do the buttons up on that coat, Virginia,” and she’d obeyed, but perhaps she should have smiled as well, or made some reply, because he’d not said anything after that; not until the mint imperial. When they were on the bus, and now, as they were walking along the road, she kept trying to scrutinize his face without being noticed. It wasn’t easy; he kept catching her eye and winking.

Clem nodded at a woman on a bicycle, and they pressed into the hawthorn hedge as a tractor rattled by with an empty trailer. There wasn’t much traffic. While they were walking, the afternoon became evening, and when Clem said, “Here we are,” she was puzzled. She thought there must be a tiny house hidden in the hedgerow, and she looked for it, warily, all along the verge, but all she saw was a narrow road turning onto a potholed lane. The lane was bounded by a low wall, and she knew then where the great silence was coming from.

Virginia stood on tiptoe to see the silence beyond the wall. What she saw was a silhouette-bird perched a great distance away on a tilting wooden post, amid horizontal strips of earth, air, and water; black and pearl and gray. She saw an emptiness that she could taste on her tongue, although it wasn’t the sea. She moistened her chapped lips and gathered herself to ask her first question.

“Clem?”

But a car was coming toward them on the main road, sleek and quiet and all but invisible in the dusk. The blackout laws forbade light, for fear of guiding German bombers, and it was presumably in obedience to this that the car had only one headlight, which was fitted with a slit mask. It drew up beside them, and Virginia forgot what she’d been going to say.

“Wrathmell? That you?” The driver had to lean across the empty passenger seat in order to shout through the window. It would have been easier for him if Clem had gone to the other side of the car, but Clem stayed put at the top of the narrow lane, holding Virginia’s hand. He didn’t even stoop so as to come level with the window.

“Evening, Deering.”

The driver’s face was pale, and it seemed to glow in the twilight.

“Oh! Is this…?” He indicated Virginia with a nod, and although Clem made no perceptible response, the man said, “Goodness! Congratulations!” as if he had.

Clem nodded.

“Marvelous thing for Lorna,” the man went on.

“Yes.” Clem’s quietness was beginning to sound like parsimony, as if talking was charged at tuppence a word.

Virginia looked at the murmuring car, with its great curling wheel arches, and longed to touch it, just to see what it felt like. It was shiny black, like a patent leather shoe.

“Well?” said the man, looking her over once more. “Do I get an introduction to the new Miss Wrathmell, or not?”

Clem lifted his gaze over the roof of the car and squinted at the sky. “Virginia, this is Mr. Deering,” he said. “Mr. Deering, Virginia.”

Mr. Deering pulled his driving glove off with his teeth and stretched even farther across the passenger seat in order to proffer his hand. Clem nudged her gently in the back, so she approached the car and gripped the outstretched fingertips. Mr. Deering laughed and said, “A breath of fresh air! Just what we need around here!” and Virginia was surprised by a squeamish desire to remove her mitten and touch his handsome moustache, to see what that felt like. It was the same shiny black as the car, and it didn’t look as if it was made of hair. Perhaps he painted it on every morning, with a thin brush and a little pot of lacquer.

“What age?” said Mr. Deering pleasantly, over her head.

“Vi was ten in August.”

“Ah-ha. Same age as Theo. Perhaps a spot of matchmaking is in order? What do you say, Miss Wrathmell? It’s his birthday party on New Year’s Eve.”

Virginia stepped back to the verge and Clem reclaimed her hand.

“Next year, perhaps.”

Virginia thought it a rather awkward refusal, but Mr. Deering didn’t seem to mind.

“Well,” he continued pleasantly. “Hop in, both. Won’t take a minute to run you down to Salt Winds.”

Clem tightened his hold. “Thanks, Deering, but we’ll walk.”

“Bit of a stretch for little legs, isn’t it?”

Something whistled across the silence—a rising, bubbling echo that repeated again and again—and the men stopped talking in order to listen. Virginia thought of a piccolo.

Clem took a quick breath and looked up, as if he’d heard a cautionary whisper in his ear. There was a new resolution in the way he said, “Listen, Deering, we should catch up properly, and soon. Perhaps you’ll bring the children to Salt Winds in the New Year, once Vi’s had a chance to find her feet? Afternoon tea, or something?”

Mr. Deering withdrew from the passenger window and sat up properly in his own seat. Virginia studied him in silhouette as he pulled his glove back on, wiggling the fingers until they were straight and tight.

“That would be marvelous,” he called. “I’ll hold you to it.” Virginia could tell he was still smiling, even though his features were invisible. He pushed some pedal, or pulled a lever, and the purring motor roared, drowning out any goodbye. Clem didn’t have a free hand, but he raised the little suitcase in salute as the car disappeared around the bend in the road.

Tollbury Marsh is good for birds but bad news for people, so you must promise me that you’ll not set foot on it. Never ever. Understand?

Clem squeezed Virginia’s hand and led her into the narrow lane. She wished he’d said “Yes” to Mr. Deering’s offer of a lift, because her shoes were pinching and the lane seemed to stretch on for miles, straight as an unrolled ribbon, without letup. If you followed it for long enough you came, eventually, upon a gray square, which might be a house—but it was a long way away.

“Here,” said Clem, putting the suitcase down and poking about in his coat pocket. “Have another mint to keep you going.”

This one was a humbug, and it had stuck, over time, to the bottom corner of a paper bag. Clem peeled most of the paper off in tiny, white shreds, and she popped it into her mouth.

“Do you want to walk on the wall?” he asked. Virginia responded with the beginnings of a smile, and he helped her clamber up on her hands and knees, both of them careful not to scuff the navy coat, or catch it on bird muck. The top of the wall was wide and undulating, like a stone road, and when she stood tall and looked down the lane, the top of Clem’s hat was lower than her shoulders.

They started walking, and Virginia glanced at the flatness to her left. It was too dark to see the silhouette-bird now. The deep, arctic blue of the sky was reflected, here and there, in streaks of water, and there was a single star in the sky, but everything else was dark. There was a low, cold wind that Virginia hadn’t felt when they were coming from the village, and it numbed the left side of her face as she walked.

The humbug flooded her mouth with minty saliva as she passed it from cheek to cheek, but it hardly shrank at all, so she bit down on it with a loud crack.

“Steady on, old thing,” said Clem. “You’ll have no teeth left.”

She laughed at that: a breathy, stifled sound, which encouraged Clem to go on. “Lorna will be put out if you arrive without teeth. I can hear her now: I could swear that girl had teeth when I last saw her.”

“What will you say?”

“I’ll say, ‘Stop your nagging, woman, she had them all in this morning. I reckon she must have taken them out and left them on the bus.’”

Virginia was outraged; she could barely speak for laughing. “I don’t have false teeth! Look!” She stopped and bared her teeth in a fierce grimace.

Clem looked, but before he could say anything the whistle noise sounded its repeated echo across the emptiness, and Virginia forgot about her teeth. She looked left, across the void, and fixed her scarf so that it covered her chin as well as her neck. Her breath dampened the knitted wool, and made it prickle against her lips.

“Clem?” she said. “May I ask you something?”

“Anything. Fire away.”

Virginia hesitated, because he’d said “anything,” and she took him at his word. She saw half a dozen questions lined up like fancy chocolates in a box, and it was hard to choose a favorite. She was tempted by the chance to find out something about Mr. Deering, but her nerve failed and instead she chose “What is that whistling sound?”

“A curlew. It’s a type of wading bird. There are lots of birds on Tollbury Marsh; they like it here. I can tell you all about them, if you’re interested. All their names, and so on.”

Virginia nodded eagerly, and, as if by agreement, they stopped walking and stared into the wind. She already knew that Clem made his living by writing books about wildlife. It had surprised her, when she first found out, because Clem didn’t look like a writer; he looked too sturdy and weathered, as if he spent all his days outside. Of the two Wrathmells, it was Lorna who came across as the rarefied, indoorsy one, and on one occasion Virginia had plucked up the courage to ask whether she was a writer too. The three of them had been sitting in the visitors room at Sinclair House, and Lorna had smiled at the question, but before she could answer, Clem had said, “I think Lorna’s got enough on her plate, looking after me. Wouldn’t you say so?”

“Is this the marsh?” Virginia asked, indicating the darkening vastness with a nod. “When you say ‘Tollbury Marsh,’ do you mean all of this?”

“Indeed I do, and Tollbury Marsh is good for birds but bad news for people, so you must promise me that you’ll not set foot on it. Never ever. Understand?”

Clem made her look at him. The upper half of his face was hidden by the shadow of his trilby hat, but she could see how his jaw set, and she nodded. The follow-up question of Why not? died on her lips.

Clem stuck his free hand in his pocket after that and walked with his head down. Virginia worried she’d done something to make him cross and trotted to keep up with him, her gaze fixed on the trilby hat, and before very long she tripped on a raised stone and banged her knee. Clem noticed straightaway, even though he was well ahead and she hadn’t cried out. Her skin was grazed, and, worse, the navy coat had picked up a smear of mud, but she managed not to cry and Clem seemed himself again as he helped her up. He spat on a handkerchief and dabbed at the broken skin.

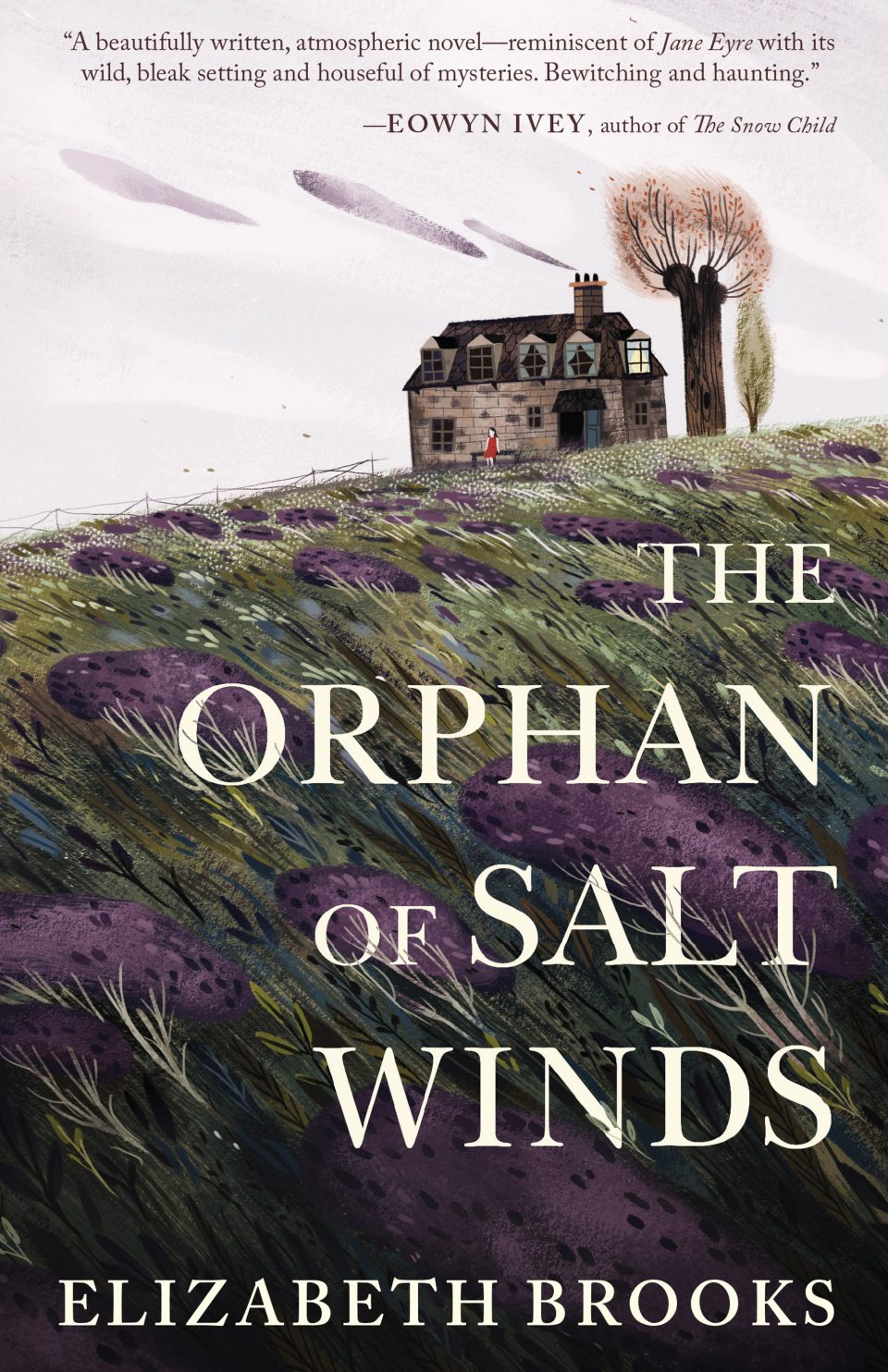

“Piggyback?” he suggested, and she wrapped her arms around his neck and shuffled onto his back. He hitched her up and they were off, much faster now. She laid her head gingerly against his neck and watched the world through the space between his hat and collar. They were closing on the gray square now, and she could see that it was indeed the front of a house, with long windows and tall chimneys. There wasn’t so much as a crack of light, and the only proof that the place wasn’t boarded up and abandoned was the smell of woodsmoke that grew stronger the nearer they came. Virginia stared up at the gaunt windows, searching each one for a sign of life, but found only reflections of the evening sky and the backs of curtains.

She closed her eyes and let her head loll on Clem’s shoulder. The drone of the wind and the rhythmic swing of his steps made a kind of lullaby. As cold and tired as she was, she didn’t want their walk to end.

“Lorna won’t be cross, will she?” Virginia was careful to speak softly, so close to his ear.

“What? About the coat?” His words vibrated against her cheek, from deep inside his chest. “She’ll have me to deal with if she does. Anyway, I’m sure she won’t. It hardly shows at all.”

Salt Winds. Virginia raised her head in time to read the name of her new home, carved in a stone gatepost.

*

Clem flicked the hall light on and eased Virginia off his back. She blinked in the brightness as Clem set her suitcase down and tossed his keys into a bowl. It felt warm inside the house, and there was a strong smell of cabbage and gravy. As soon as she could see well enough, Virginia searched for the mark on her coat and began to scrape at it with her thumbnail.

Someone was tearing about on the floor above them, slamming drawers and making the floorboards squeak underfoot. A terrier came bounding and yapping down the stairs, wagging its stump of a tail, and a woman’s voice shouted after it, “Bracken!”

Clem took his hat off and called up the stairs, in much the same tone of voice, “Lorna!” He ignored the dog, though it was racing around his feet and worrying his shoelaces.

“Clem? I’m coming, I’m coming, I’m sorry.” There was a final flurry of sound and a pause, as if she’d stopped to gather herself, and then Lorna was coming toward them down the stairs.

“Virginia,” she smiled, her hands outstretched in a gesture of welcome. “How wonderful to have you here at last!”

She wore an emerald-green dress with a narrow belt and a necklace of pearls, and she made the stairs and hallway, and even the dog, look drab. Virginia had met Lorna several times at Sinclair House, so she was familiar with that oval face; with her creamy skin and pencil-thin eyebrows and plump mouth. She hadn’t seen her yellow hair before, though, or not properly, because Lorna had kept her hat and coat on when they were sitting in the visitors room or walking about the orphanage grounds. It was the sole part of her that didn’t seem quite in control. Despite her obvious efforts to keep it combed and lotioned and pinned, curly strands kept flying loose all over, and she kept trying to poke them into submission.

“Welcome, welcome!” Lorna held Virginia at arm’s length, her hands trembling. She surveyed the child with a fixed smile and planted a perfumed kiss on her cheek.

Virginia’s voice had jammed in her throat, and she didn’t dare return the kiss, for fear of marring the powdery perfection of Lorna’s face. She cobbled together an awkward, blushing gesture instead, something between a bow and a curtsy, which made Lorna laugh uneasily.

“You must be hungry as a hunter!” she said. “Dinner won’t be long.”

Clem was on one knee, trying to extract his shoelace from the jaws of the ecstatic terrier. “How long?” he demanded, frowning up at his wife. “The poor child has walked her legs off on the strength of a sandwich lunch; she needs a quick supper and straight to bed.”

Lorna’s hostess smile barely wavered. “It’ll be five minutes; ten at most. Mrs. Hill made a splendid rabbit pie this morning while I was doing the beds. It’s in the oven now and coming along very nicely.” She turned back to Virginia and bent down, so that their faces were level. “We usually eat in the kitchen, but I’ve set the table in the dining room today, as it’s a special occasion. Do you want to come and see? I’ve put a white tablecloth out, and the silver cutlery, and it couldn’t look smarter if we were expecting the king to dinner.”

There was nowhere for Virginia to look other than her new mother’s expectant face. She felt the tears rising at the back of her eyes and contorted her lips into odd shapes in an effort to stop them falling. It was impossible to explain how much she feared the sumptuous dining room; impossible to confess she wasn’t hungry.

“I got a mark on my new coat,” she faltered, as the first drops slid down her face. It was the only sensible-sounding apology she could think of. Bracken chose this moment to notice her, and busied over to inspect her ankle socks.

“Let’s have a look.” Lorna studied the offending patch of coat and brushed it with the back of her hand. “Well, not to worry, it’s just a bit of mud. There’s surely no call for tears?”

Clem came up behind Virginia and shuffled the coat off her shoulders. “Told you she wouldn’t be cross,” he murmured in her ear. Virginia slipped her mittens off, and Clem popped them in the coat pockets, one on either side.

“But of course I wouldn’t be cross,” Lorna exclaimed, her smile hardening. “Goodness, I’m not a dragon, am I?”

Salt Winds was a large house; she hadn’t expected that. It was large enough to be a small-scale orphanage, if someone wanted it to be, although it would have to be stripped and sterilized first.

Lorna was so patently un-dragonlike that it seemed pointless to say so, but perhaps someone should have bothered to state the obvious because the ensuing silence felt heavy. A tear dropped off Virginia’s chin and splashed on the dog’s nose. It gave a shrill bark and jumped up at her like a jack-in-the-box.

“Oh Bracken, give it a rest,” said Clem, touching the dog’s belly with the toe of his shoe. Bracken snarled and pounced, catlike, on his master’s foot. Virginia smiled at that, so Clem teased it all the more, moving his foot around the wheeling terrier, with one eye on the child’s tear-stained face.

All at once Bracken stopped chasing and began to bark in earnest.

“Stop it!” Lorna swooped on the dog, smacking it hard across the nose. Clem winced. When Lorna hoisted the animal into her arms, its back legs scrabbled and pulled threads from her dress, but she didn’t seem to notice.

Virginia shuffled closer to Clem until she was half-hidden by his arm, and Lorna glanced at the pair of them, a blush rising up her neck. “I’ll check on the pie,” she muttered, stalking off with the wriggling terrier still in her arms. Clem ruffled Virginia’s hair. “I’d better go and offer my services to the chef,” he whispered.

He showed her into the dining room where a snow-white cloth was laid, as promised, for three. A wood fire crackled in the grate, and the silence was like velvet, except for the occasional clatter from the kitchen. “Have a seat, Vi,” he said. “Give those poor old feet a rest.” He hovered in the doorway for a moment, as if reluctant to leave, and she managed to smile at him over her shoulder.

After he’d gone she stood by the fire for a moment, with her back to the warmth. The dining chairs were made of dark wood with tapestried seats, and she had to tense both arms in order to pull one out. At first she was content to sit on her hands and watch the firelight dance on the cut-glass water jug, but after a while she picked up her knife to find out if it was as heavy as it looked. It was even heavier, so she tested her fork, and her crystal glass, and after that she slid the silver ring off her linen napkin and rested it on her flat palm.

Salt Winds was a large house; she hadn’t expected that. It was large enough to be a small-scale orphanage, if someone wanted it to be, although it would have to be stripped and sterilized first. The ivy-patterned wallpaper would have to be painted over, and the threadbare carpets replaced with linoleum. The greenish curtains would have to be mothballed and replaced with safety bars. There would be no more leather-bound books on the shelves, no glass-fronted cabinets, no china shepherdesses on the mantelpiece. She twisted in her chair, perversely pleased by her snap calculations. Some of those age-dulled oil portraits might stay on the walls, but the framed photographs—the family weddings, the men with dogs and guns, the sepia babies in sailor suits—would go.

She jumped when the door squeaked, but it was just Bracken nosing his way in. He padded across the carpet, ignoring her proffered hand and friendly cluckings, and slumped down in front of the fire. The voices in the kitchen were a muddle of sound. A tap gushed, and when it stopped she caught the end of Clem’s question.

“. . . that the two of you enjoyed your little tête-à-tête in my absence?”

Virginia barely recognized his voice, it was so stony and hard.

“I don’t know what you mean!” Lorna hissed. “Where did you get that from?”

“Straight from the horse’s mouth. He came cruising by when we were walking from the bus, and passed on his ‘congratulations.’ Well, who told him, if not you? He even gave me a little lecture on ‘what a marvelous thing it is for Lorna’—he being the great expert, of course.”

“I’m sure he did no such thing,” said Lorna tightly. “Mind out of the way, this is hot.” Her voice moved to a different part of the kitchen. “If you must know, we met by chance in the line at the post office. He asked after you, and naturally I told him you’d gone to fetch Virginia. What’s wrong with that? She’s not some unmentionable secret, is she?”

Clem sighed, and there was a long silence between them.

“No, of course not.”

An oven door slammed shut. Plates were fetched from a rack and stacked angrily, one by one.

“I’m surprised he didn’t offer you a lift,” Lorna observed.

“He did.”

“But you walked?”

“I wanted to. It was our daughter’s first view of Salt Winds, Lorna; I’d pictured it so often in my head.”

“You made Virginia walk all the way up the lane, when Max could have driven here in five minutes flat?”

“I’d rather not be beholden.”

“Beholden? Oh, for God’s sake—” Lorna’s voice stopped abruptly. There were scuffling noises and fierce whispers, and the sound of someone trying not to cry out. Then there was silence.

Bracken raised his head from his paws and cocked his ears. Virginia held tight to the sides of her chair and fixed her gaze on the water jug. The cut glass made a miniature world, so beautiful and complex that if you stared at it for long enough you could lose your way among its flickering slivers of light.

__________________________________

From The Orphan of Salt Winds. Used with permission of Tin House Books. Copyright © 2019 by Elizabeth Brooks.