The Origins of Diane Arbus’s Most Famous Photograph

Revealing the Mysteries of Identity through "Human Multiples"

Arbus attended a Christmas Day party in 1966 that was held by the Suburban Mothers of Twins and Triplets Club of Roselle, New Jersey. It wasn’t her first time prospecting for human multiples on the other side of the Hudson. Three years earlier, she had shown up at a similar event in New Jersey seeking subjects for her camera. That time she met the Slota family and received an invitation to follow them home to Jersey City and photograph their girl triplets. She posed the sisters at the dining room and kitchen tables, in their parents’ bedroom, on the living room sofa and, many times, including the image she selected, in their shared bedroom. Dressed identically and primly in buttoned-up white shirts, white headbands and long dark skirts, they sat together on the middle bed in a room with three close-set identical beds and a wall decorated with a repeating pattern of diamonds. The girl on the left folded her hands and looked earnest. The central one appeared placidly content. The sister on the far right gazed with a faintly troubled expression and lightly gripped the shoulder of the triplet in the middle. Against the machine-made repetitions of the surroundings, each girl projects willy-nilly a human individuality. For Arbus, the triplets embodied a symbolic psychological narrative. “They remind me of myself, my own adolescent self,” she said, “lined up in three images, each with a tiny difference.”

The triplets photograph was such a success that Arbus wanted to explore the theme further. Attending the 1966 Christmas party in Roselle, she found the event “terrific” and “phenomenal,” but it didn’t provide her with the lineups of identical twins and triplets that she had envisioned. The children weren’t all identical, and the ones that were didn’t compose themselves in uniform groupings. She needed to pose them, even though she claimed she never did. “I don’t like to arrange things,” she said. “If I stand in front of something, instead of arranging it I arrange myself.” But that professed stance was in itself a pose, a pretense, an exaggeration. She wasn’t a street photographer, prowling with a Leica to catch a picture in motion. Covering competitions, she had learned that the contestants, judges and spectators usually wandered here and there, failing to fall into place within the view finder. Depending on the requirements of the photograph, to a greater or lesser degree she arranged her subjects. Yet, as she frequently emphasized, she wasn’t a fashion photographer, either. When she directed people, it was to bring out their own qualities—or, at least, the qualities that she saw in them.

At the party in Roselle, in a Knights of Columbus hall, she encountered twins and asked to photograph them side by side. She got them to stand shoulder to shoulder and depicted them frontally against a blank wall. There was nothing innovative in their pose or her camera position. In particular, a striking formal similarity exists between these photographs and those that August Sander made of paired subjects—sometimes of siblings, including twins, who wear the same clothing and stand close enough to overlap. Arbus likely found inspiration there. But the differences from Sander, in her aims and results, are telling. When Sander photographed two farm-girl sisters dressed identically, he created a portrait of distinct individuals who had been cast in the same role. Looking at Sander’s portraits of children, you see the youngsters as seeds. With individual bumps and wrinkles, they will sprout into recognizable specimens of their society.

The socioeconomic position and future of the twin girls who are the subjects of what would become Arbus’s most famous photograph cannot be surmised or teased from their image. Nothing in the picture would let you know that Colleen and Cathleen Wade were two of the eight children of a white-collar worker in the employee relations division of the Esso Research and Engineering Company (later rebranded as Exxon). You could, perhaps, correctly conjecture that the dresses the sisters are wearing, with big, at white collars and white cuffs, were made by their mother. But that is not where the picture takes you. What it indelibly evokes is the duality of a human sensibility. Because the twins are so alike—even the two bobby pins that x in place their white headbands are arranged in precisely the same way—a viewer focuses on the subtle distinctions between them. The one on the right smiles angelically. Her eyes are bright, her bangs are neatly combed, and her stockings are drawn up. The sister on the left is a bit less carefully pulled together. Moreover, her expression is slightly off. Her eyes are hooded and her mouth is pursed. She appears to be a hidden personality of the first girl, a baleful doppelgänger. For an artist who, from early adolescence, had agonized over the presence of “evil” within herself, the photograph could represent the visualization of a darker alter ego. Diane’s psychological motivations aside, the portrait delves deeply into the mysteries of human identity.

“What’s left after what one isn’t is taken away is what one is,” Arbus wrote in her notebook in 1959, early in her independent career. This tenet on the essential kernel of every individual had a practical corollary: to reveal the fundamental, a photographer must exclude what is extraneous. More than a decade later, she made the same point to her students: “I mean we’ve all got an identity, you can’t avoid it. It’s what you’ve got when you take everything else away.” Eliminating all distractions, the photograph seems to plumb the nature of the two girls. As the backdrop of a light-colored wall and a dark brick floor fades into insignificance, the eye of the spectator searches to make distinctions between the identical twins wearing identical outfits. A keen observer—and there is no eye sharper than Arbus’s— will notice that despite the congruence of tiny details (“Look at those bobby pins!” she exclaimed) the clothes aren’t precisely the same. For one, there are slight differences in the hems of the dresses. “And then there’s this incredible thing,” the artist said gleefully when discussing the picture in public, “which is they’re wearing stockings that are very, very similar, but different.” Yet if those subtle variations help bring life to the portrait, in the way that an orchestra conductor’s tiny modulations enhance the performance of a symphony, the overall impression remains that the girls are identically dressed. A modernist architect or designer would approve. All superfluous ornaments have been stripped away. The structures are expressed on the surface, the facts of personality and character exposed.

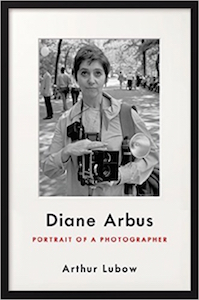

And yet, if the portrait of the Wade sisters, like that of the Slota triplets, suggested merely the changing states of a single personality, the photograph would not exert such force. It would not have become, through its evocation [see featured image, above] in Stanley Kubrick’s film The Shining and countless other reproductions, an image almost as iconic as Edvard Munch’s The Scream. Its chief quality is instead something otherworldly, a haunted stillness and strangeness. A believer in the supernatural might imagine the girls—or, at least, the twin on the left—to be possessed by an evil spirit. They might have walked out of one of the ghost stories that Diane read to her class during the New York City blackout. Unlike surrealist montages and manipulated images, which Arbus scorned, her portrait of the Roselle twins is as clear and direct as a family snapshot. Nonetheless, the girls’ parents disliked the print when Arbus sent it to them, and they put it away. “We thought it was the worst likeness of the twins we’d ever seen,” Bob Wade admitted.

Freud, in his essay on “The Uncanny,” describes how artists introduce devices that successfully evoke an impression of what in German is called the unheimlich, or, literally, the “unhome-like.” One way is by creating doubt in the mind of a reader as to whether a figure in a story is living or inanimate—such as the doll, Olympia, in E. T. A. Hoffmann’s story “The Sandman,” and in Offenbach’s opera that is derived from Hoffmann’s tales. Photographers, from the early days of the medium, have known that a living person can seem dead in a picture, and conversely, a photo- graph of a sculpture can appear to be alive. Arbus’s photographs of the murderers in the wax museum exploit that ambiguity. But another ploy that Freud cites, and one that particularly comes into play in her photograph of the Roselle twins, is the appearance of an identical double who arouses dread—in Hoffmann’s novel The Devil’s Elixirs, for instance, and in Edgar Allan Poe’s story “William Wilson” (which Freud does not mention). From his psychoanalytical perspective, Freud regarded the uncanny as the emergence of something familiar that has been repressed. Its appearance elicits recognition, and, at the same time, fear or horror. He emphasized that if the overall setting is fantastic, as in a fairy tale, the effect does not arise. It is only when the odd occurrence is inserted into an otherwise conventional and realistic background that the uncanny flicks its feathery brush and our spines tingle. Arbus had three books by Freud in her library, but not this essay, which she may never have read. Nonetheless, she understood, as she put it approvingly, that “a fantasy can be literal.” Unlike surrealist artists who attempted to represent what they saw in their minds, she found her fantasy by looking closely at the world around her. Reality is what confronted her camera. “I mean reality is reality,” she once said, “but if you scrutinize reality closely enough . . . or if in some way you really, really get to it, it seems to me like it’s fantastic.”

From Diane Arbus: Portrait of a Photographer. Used with permission of Ecco. Copyright © 2016 by Arthur Lubow.