7 November

I’m sorting things into categories – items to be thrown out, those to be given away. I can’t help smiling as I realise I’m following the advice of decluttering influencers. A cold light filters in through the window. Spiders are clustered in corners and all around the stove. They don’t seem to have spun any webs. I find dead ones in pots and pans and dispose of them. I’ve decided to start in the kitchen, somehow it has fewer associations than other rooms. Anything that’s passed its sell-by date goes straight into a bin bag. Mustard, tomato concentrate. A jar with a lump of something white – duck fat. A whole shelf of cheeses. The fridge shudders as I launch my attack. The freezer compartment needs defrosting. The plastic has cracks in it. Véra’s only been coming back here once a month since she moved out. Potatoes in the vegetable drawer have sprouted. The smell from the cheese makes me feel nauseous. I work quickly. Mouldy jam, almost empty packets of butter, bunches of wilted herbs.

Véra is busy in our bedroom. Her presence in the house unsettles me. I listen for sounds from her. She came downstairs a little while ago to make herself some coffee just as I was sniffing a jar of stewed fruit. She asked me if I wanted some. I didn’t know if she meant coffee or stewed fruit and dumped the jar of fruit into the bin, like a rabbit caught in the headlights throwing itself under the car.

Véra’s making progress too. I’m worried we’re going to end up having too much time on our hands. What will I do with her for another six days? I make a conscious effort to work more slowly.

The kitchen is a mess. It looks more like the Véra I remember. I prefer that to the way the living room was when I arrived, all neat and tidy. Oil has leaked all over the counter. I clean up the pools of fat and lumps of grease. As I’m wiping the cloth over the bottom of a cupboard I feel a loose panel. It comes away easily when I press harder. Behind the panel there’s a space the size of a vegetable crate cut into the stone wall. It’s full of bottles of strong spirits, packets of sugar. I call Véra. She wasn’t aware of this alcove either. Does she think perhaps our father was . . .? She shakes her head, probably not. I agree, I never saw him drinking either.

‘And Maman?’

Véra looks thoughtful. I pick up one of the bottles. Quince liqueur. When I go to put it in the bin, she stops me, mimes us drinking it from the bottle. I shake my head but put it back and close the secret hiding place. I turn my attention to the sink – globs of jam floating in brackish water. I have to plunge my arm right in to fish them out.

Véra seems impressed by my system of organising. She looks at me, tugs at her jumper and points to the stairs: she wants me to go up and sort through my clothes.

‘I’m giving them all away.’

She insists. I’m conscious of her watching me as I climb the stairs. I can feel the weight of her gaze, it makes even the most trivial gestures seem significant.

My side of the chest of drawers is the same as it was before I left for the US, minus one or two jumpers. I decide to try on a pair of jeans anyway. Just for fun. My father had mended a hole in them by sticking on a patch with a flowery motif. He did it with a pan of boiling water. The jeans are loose on me. I must be thinner than I used to be. I’m surprised, I’ve put on weight these past few months. Irvin likes it, which I find both comforting and worrying. I put the jeans in a bag along with the flannel trousers I never wore. Cotton pyjamas, T-shirts, woollen jumpers. I rummage around, feeling more and more that I’m looking for something.

‘Where are my skating outfits?’ I ask Véra as I come down the stairs carrying several bags.

She hesitates, gestures vaguely with her hand.

‘You threw them out?’

She shrugs as she walks back upstairs: apparently, I told her to do what she wanted with them.

There’s a saucepan left out on the hob. Spiders teeter along the handle and scuttle away to hide under the furniture.

*

In the afternoon we go out. To get to the woodland paths you have to walk through the vegetable patch. The raspberry bush is still doubled over after last night’s downpour. The carrot tops and radish leaves too. Véra is pleased, we’ll have plenty to eat.

‘And pasta,’ I say.

Véra taps her fingers on her belly. She’s trying to cut down on gluten. I glance at her flat stomach, I can see she still exercises regularly.

‘All these fads,’ I say. ‘I’m so fed up with them. When you live in New York it’s one thing after another: organic hemp milk, avocado toast, seeds.’

Véra nods slowly in agreement.

The path runs alongside the stream. The ground is red and orange, covered with fallen leaves after the storm. Most of the trees are white oaks. I scoot along in my old boots, crushing slugs underfoot. My father always insisted on buying me boots a size too big, he was convinced my feet were still growing. I’ve ended up wearing a size smaller than I did then, probably from years of squeezing my feet into high heels.

The vegetation grows denser, we have to duck our heads as we walk. Véra clears the brambles using her secateurs and a stick. Her cheeks flush a dark red. She has rosacea. I try not to think about how unattractive it is. I can barely see her among the trees, she’s camouflaged by the brown patchwork jacket she’s wearing.

*

I’m annoyed about my skating things, I don’t remember giving her permission to get rid of them. Not that I’d have ever worn them again.

I don’t know how I did it, pushing my body to the limit out on the ice like that for so many hours each week, ankles straining to balance on the blades, tendons inflamed, music blasting from speakers.

During the winter we trained in a temporary structure erected on an industrial estate on the outskirts of Périgueux. The rest of the year, we did artistic and rhythmic gymnastics to maintain our fitness. I started quite late, when I was eight. My dream was to make it into the club in Limoges or one of the other cities further north. I used to catch the first bus at six in the morning to go and practise alone on the ice before school. The group sessions were in the evening. After practice I’d wait for the bus in front of the cathedral. I would go inside the cathedral and do my homework by candlelight. There were usually plenty of votive candles already burning but sometimes I’d light them myself. You were supposed to put money in the box but I never did.

We arrive at the pond in the dell. The surface of the water is smooth and black with peat. Down here there’s no wind. A figure of a woman carved in stone crouches on one of the rocks in an outcropping near the bank, her face turned towards the water. The château looms above us, curved in on itself like a snail, the tower and the pigeonnier its antennae. We take the shortcut through the limestone rock, along the cluzeaux, natural galleries that were supposedly once used as shelters. The path is quite steep in places. Véra hops and skips to avoid the mud. I’m amazed at her level of energy. I don’t talk. I don’t want her to notice that I’m out of breath.

The hedges beyond the gate need trimming. The kitchen garden is overgrown. Through the open stable doors I can see stalls, a car, two donkeys, one with strangely cropped ears.

Octave’s tall figure appears, wearing a green raincoat. Véra hurries to meet him. I watch them as they hug, they seem to be close. I hang back, taking in Octave’s height. He’s thirty-five, five years older than I am. He’s always been tall but now he seems immense, out of reach. Véra looks so tiny in his arms. He turns to me and says:

‘The American! Finally!’

Without waiting for me to respond he starts leading us towards the recently renovated tower. On the way we walk past the pigeonnier. I’ve never seen it like this before, surrounded by scaffolding and draped in white. Disjointed, recovering from injury.

A damp draught blows from the stairwell. Octave warns us to take care, the walls are thick and the steps are surprisingly narrow. We follow him up the stairs, exchanging platitudes as we climb. He’s gleaned a little about me from the press and social media. He tells me he’s still working with the University of Limoges as an environmental archaeologist. I have no idea what that involves.

‘It’s basically studying the way human societies interact with their environment,’ he says. ‘We look at the historical impact of humans on the environment, the way various living things have responded. Plants and animals, as well as humans.’

He stops and turns to us before adding:

‘What we’re actually trying to do, of course, is work out what’s going on right now.’

The first floor of the tower is used for storing fishing gear. Véra inspects the jars of dried worms, tests the weight of the rods, runs her finger over the blade of an axe that must date from the Middle Ages.

I go on up to the second floor, Octave following on behind me. High ceiling, disused fireplace, pumpkins lined up along one wall. A plastic bat has fallen from a wire hanging from one of the beams. Octave pulls a face, says his daughter wanted to have a party for Halloween, he hasn’t had a chance to clear up. He’d tried to make a four-poster bed. I look down at the mattress sitting on top of pallets, a fishing rod planted at each of its corners. I try and imagine him as a father. I ask how old his kid is, doing my best to sound offhand.

‘She’s five.’

‘Is she here with you?’

‘She’s at her mother’s, for the holidays.’

He scrapes his hand over his face as if he’s trying to erase something. Looking down at my feet I catch a glimpse of Véra still peering at the jars on the floor below. I can see her through the gaps between the floorboards. I walk over to the window. The glass is cracked, the pond and the statue just visible.

‘I’ve ordered stained glass windows,’ Octave says.

I make a joke about the name of the château, Le Pigeon Froid, the cold pigeon. He smiles gently.

‘I know, it’s not very appealing.’

Véra comes up to join us and we resume our climb. Octave wants to show me the renovations to the battlements. Outside, we look down through the gaps in the parapet from a dizzying height. The tower dates back to the twelfth century. It’s one of the most ancient structures in the region. Octave starts explaining about the machicolations, how they were used for defence. I can’t help feeling irritated. The explanation is for my benefit, Véra already knows all this. I do too, he ought to realise that. He used to come to our house often enough to borrow books from my father.

I kneel down, feeling dizzy. Cold sunlight on the burnished countryside, the village set out below, buildings scattered like ruins marked out in an archaeological site. Octave says the population has shrunk to the lowest numbers ever, thirty-three, including the smallholders and the artisans who work at the Hermès plant and the knife factory in Nontron. The school has closed down. But the fromagerie is still there, supplying cheese to gourmet restaurants as far away as Sarlat and Rocamadour.

There’s a clear view of the pigeonnier across the courtyard. Looking at it from here you wouldn’t know there had ever been a fire there. It happened a hundred years ago. No one knows how it started. My father had plenty of theories, he was always talking about it. I never went inside. The door was always jammed shut. I still think about the birds trapped in there, unable to fly out. I imagine macabre scenarios – are there skeletons in there still? Is the floor carpeted with the incinerated remains of the birds that perished?

In the gathering darkness of late afternoon, the pond has melted away. Only the statue is visible, her neck twisted by a trick of perspective. No longer gazing at the water, she seems to be trying to catch our eye.

Véra brushes my sleeve lightly to let me know she wants us to leave. On the way back, as we pass the stable, I look more closely at the donkey with cropped ears and realise it’s a llama.

*

In the evening I go up to the bedroom before Véra and do some work in bed. My emails have been mounting up. The internet connection keeps dropping out. There are six of us working on the screenplay. I haven’t met any of the others in person. When we first embarked on the project I suggested we get together for a meal and a work session. Everyone agreed it was a great idea. Six months later I’d still had no response to my suggested dates and had to accept that we’d be doing all our communicating online.

The novel we’re adapting is structured in two alternating parts. One is an autobiographical account of Perec’s memories of his childhood during the second world war. The other describes a fictional island dedicated entirely to sport, which gradually emerges as a metaphor for the concentration camp in which his parents perished.

I read over the ideas I drafted before leaving New York. They seem less interesting now. Moonlight filters through the window, streaking the ceiling. I savour the silence. I still haven’t adjusted to the sirens in New York. A spider twitches above my head. I could reach out and touch it. I never see any in New York. I watch it carefully, in case it decides to weave its web right next to my face. The spiders are the reason Véra has the bottom bunk. When we were growing up, we used to get into bed together more and more frequently as tension mounted between our parents.

‘Don’t worry, Véra,’ I’d say over and over again, cradling her in my arms. ‘Everything will be all right, you’ll see.’ I was never really sure which of us I was trying to reassure, Véra or myself.

I find it hard to remember that we were inseparable once upon a time. We were both timid. Both fearful of social interactions. We didn’t squabble. We were bound together by our shared language of silence and cries.

I can’t really remember how her silence began. Véra was six. We were eating, my father, Véra and I. My father asked her a question and she didn’t reply. We thought it must be a tantrum of sorts. My mother wasn’t there, she was working. My father grew impatient. Véra started breathing hard, her face contorted. Strange sounds came out of her mouth, somewhere between groaning and gurgling. Choking. She never uttered another word after that. I don’t know what it feels like to her, but I do know that since I had the epidural, I’ve understood how frightening it can be to have the impression you can’t breathe. You think you’re dying, you start to black out.

Véra never complained of any physical or emotional trauma. The doctors said the most likely cause was a ruptured aneurism, rare as that is in children. The speech therapists explained the situation to us, making it clear that aphasia can take many forms. Every case is different. Some individuals can understand the written word but are unable to speak coherently, others confuse words, saying things like ‘ballot’ instead of ‘rabbit’, or they fail to realise that what they are saying makes no sense at all: ‘I’m cold’ for example when they mean ‘I love you.’ For the family, the advice is always the same: be patient, ask simple questions that can be answered with a nod or a shake of the head, speak slowly, don’t finish sentences for the person suffering from aphasia, and don’t correct their mistakes. But what about with a child? Where do you draw the line between a disability and a normal process of learning? My father asked if there could be a psychological cause. Probably not. I think this uncertainty was the most painful aspect of it for me. I was never able to let go of the suspicion that Véra had intentionally denied me access to her inner world.

__________________________________

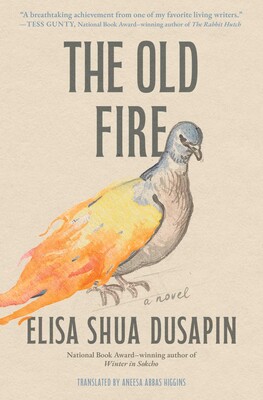

From The Old Fire by Elisa Shua Dusapin, translated by Aneesa Abbas Higgins. This book was first published in the United Kingdom in 2026 by Daunt Books Originals Copyright © 2023, Éditions Zoé. Published by arrangement with Agence littéraire Astier-Pécher. English translation copyright © 2026, Aneesa Abbas Higgins. First published in French as Le Vieil Incendie by Éditions Zoé, 2023 Used with permission of the publisher, Summit Books. Copyright © 2026.