A priest is only a priest, even if he knows Latin, which would be notable. When all is said and done, what are priests for? Yes; for holy oils, for Extreme Unction. The Priest could only think about his fate in the midst of the conflagration that burned throughout Spain. He did not know what to do, he feared for his sins. He had said and done irreverent things. His greenish cassock seemed to incriminate him as an accomplice in the rebellion and he wanted to get rid of it by whatever means. Therefore, he made a decision.

The Priest decided to become an intellectual. He changed his outfit, put on a sweater half-eaten by moths, and picador pants. Then he entered a telegraph office, and with the thick, blackish ink that the state freely provided for short notices, that devil of a priest wrote a ballad in five minutes. It was a ballad exactly identical to the thousands of ballads written by Spaniards and Spanish-Americans since the Moors stopped writing them. In sum, a scribble. But when he presented himself before the comrades of the Union of Intellectuals, with that look on his face and that yellowed paper in his hands, they were filled with enthusiasm, and linked arms to make a chair to carry him into the main hall. Those present glanced at what he had written and hurried to affirm that it was true peasant poetry.

“Are you a peasant?” they asked him.

“Yes, brothers,” replied the Priest, humbly bowing his head forward to adequately mimic the labors of the harvest.

“Here there are no brothers! Here we are all comrades,” objected one of those intellectuals, a tall fellow, who was skating on the waxed floor. To which the Priest replied, “Well, yes, comrades. I am a peasant, comrades.”

“Long live the peasants!” cried a choir of voices. Another intellectual, who never knew what was going on, asked perplexedly, “Where are the peasants?”

“That fat fellow there is the peasant,” someone explained to him. “He is a peasant poet, a poet of the people.”

“Long live the people!” they cried again.

A few of them grabbed him and sat him on top of the piano. The Priest saw that he was saved, and to express his gratitude, told the intellectuals (who contemplated him dumbfounded trying to find out what true peasant poets were like), that if they behaved themselves he would teach them to fill silos and mend petticoats, as well as other practical chores of rural domestic life. They assured him that they were going to treat him like a princess, that he would see he would have nothing to complain about. The Priest excused himself and hopped away, shutting himself in a WC. He instantly prepared another ballad like the previous one, about which the intellectuals of both sexes who were wandering around were again enthused. Nonetheless, scared half to death by what had happened and for fear of what could happen, they bolted in fear each time they heard the boom of a distant explosion.

Now the Priest climbed onto the piano by himself. The intellectuals surrounded him and begged him to read the romance aloud, which the Priest proceeded to do right away. After reading it, he handed out autographed pieces of his cassock, in order to surreptitiously get rid of it, since the cassock could be seen through the holes of the sweater. He explained to his new comrades that this was how black his shirt had turned from the sweat of long years working the land of a Cordoban estate. He was explaining this when the reverberation of a bomb was heard, in the distant front lines.

“The . . . cannon fire . . . doesn’t . . . frighten . . . you?” asked a writer who was passing by, whom his comrades glared at, not without anger.

“No” assured the Priest. “For me the cannon shots are like farts.”

The intellectuals went away repeating that sublime phrase to one another, with a thousand fussy affectations, as it expressed the spontaneity and frankness of the peasant. They thus considered a decision to call him Hero Poet and Peasant from now on. But they left the decision for later, until Comrade Atún, a half animal of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, could grant his approval. In a flash, he left the Union building to engage in pertinent consultation with his immediate superiors.

The Union had been set up in a palace of the Marquis of Corozal. Like the majority of those palaces of the Spanish nobility, it smelled of rats and latrines. A group of intellectuals was examining, in a corner, a collection of photographs of the marquis and marquesa, along with two more subjects also of both sexes, composing the most improbable erotic scenes.

“A lot of those must have been retouched in the darkroom,” surmised Rosario del Peral.

“Why?”

“Because there are seventy-two postures there and only forty-nine can be formed.”

Another group nearby, commented heatedly on the depravity of the aristocracy, so clearly revealed in the photographic series.

“What degeneracy! How disgusting!” said a short and chubby comrade with a little black cap on his head, who was walking about, disdaining everything. Another, with a childlike face, added: “And dirty . . . even women!”

“Yet they are gifted acrobats. You can’t deny that,” added another.

Several writers and poets laughed, and others ran to he who had spoken that last phrase and smothered him with kisses, since it was the phrases that they loved above all. In the group that was discussing the degeneration of the upper classes in capitalist society, someone explained in full detail each of the situations portrayed. He did not need to look at the photographs. He knew them by heart. Except for one; what always escaped him was when it came to the second woman, who was underneath the marquis and by the side of the marquesa, facing the other fellow. He had to go up to the group and ask them, to please let him have that photo for a moment, to which they gladly complied, handing him photo number thirty-seven, the one he needed.

The Priest was all eyes and ears to everything that was happening there, and he was already considering a new romance. Once he had thought about it for only an instant, without writing it at all, he let loose right there at the top of his lungs, climbing on to a large Bohemian crystal chandelier. As soon as he finished, his comrades flocked around in a warm embrace. Yet not everyone could embrace him. And not because of how disgusting he was, full of drool, ash and dandruff, but because at that very moment there was a phenomenal explosion with a great crash and shuddering aftershocks. The intellectuals disappeared like lightning bolts, spreading out to every nook and cranny of the house. Later, each of them had a reason to explain their sudden absence.

“I leaned out the window, to see who had been so insolent.”

“I thought I’d heard the telephone ring.”

“I went to turn out the kitchen light.”

“I ran down to the street, to defend the Union.”

“I thought it was the neighbors making a racket.”

“I remembered that I had an appointment at five o’clock. Then I realized it was for tomorrow.”

“I thought I heard someone at the door.”

And so on. Even Valerito, a fool who had never even written romances before, began to try it out that very morning, to see if he could avoid going to the front. He had offered to guard the Union, and entered the great hall at full speed carrying his rifle backwards, and quickly squeezed himself under a rug. He left his refuge again when a group of intellectuals stepped on him unawares and without him realizing he was being stepped on.

The Priest, abandoned in a corner, set himself to writing another romance on the wall. The theme concerned the explosion of an enemy bomb. He scratched it in the stucco with his own nails and right away all the intellectuals raved about the new draft. But some writers and poets began to feel the twinge of envy, since the attention that had been focused on them was now diverted towards the Priest. One of them even dared to say to a comrade—although in a low voice—that the peasant poet seemed to him too chubby to be a genuine peasant poet. To which the comrade, looking around suspiciously, responded that in the future, once the class differences were eradicated, all poets would have the right to be pudgy or tubercular, as they wished.

The ostentatious crystal chandelier pried itself loose from the ceiling and shattered, wounding some of those gathered. A hell of a racket broke loose. Not for the detachment of the chandelier, nor for the wounds that its breakage had caused—which after all, were neither too many nor too serious—but because entering through the window, bellowing with joy, were María Tancreda, María Zutana, and María del Carmen, bursting with winks, guffaws, funny faces, and gestures.

“They look bourgeois!” exclaimed an intellectual. And another clarified:

“Well, for your information, they are excellent comrades”—and stuck his tongue out at him.

Writers and poets crowded around the three Marías, shouting, jumping, and clapping their hands. Only the Priest, out of fashion, pulled shreds from the rest of the cassock that was still stuck to his skin.

“Being left alone has to be worth something!” he affirmed.

“Ah! Let me sit down,” said Maria Zutana.

“Me too!” sighed Maria Tancreda. And Maria del Carmen was no less tired: “Uf! What a racket!”

“Yes, yes! Let the three Marias sit down,” was the general clamor.

“Let them sit!”

The three Marias sat on top of a lectern. They were so nervous that they just lost their sense of touch. The intellectuals, without stopping their jumping and screaming, gathered around sniffing them. Finally, María Tancreda spoke out, stifling a little cry:

“Co . . . !

She breathed heavily, and again:

“Comrades,”—some crossed themselves—“we bring great news!” “A bombshell,” repeated María del Carmen.

“Yes, yes,” interjected María Zutana,“bomb, bomb and re-bomb!” The cry broke out “Long live the peasant Marías!”

The Priest, startled to hear about the bombs, was about to spoil the party; armed with a blunderbuss, he started shooting right and left, howling, and all hell broke loose.

“Get back, enemies of the people! Down with the scoundrels and rogues! Death to fascism!”

When they explained to him that it was not a real bomb, but a metaphor, the Priest immediately said that he would recite his latest romance. They did not let him. The Marias objected. This was not the right time, said one of them. Besides, the crowd of poets and writers of the Union were moved by the enthusiastic revelry that had been stirred up by those who had recently sat on the lectern.

“Well—” María Zutana began,“we have won over Don Gregorio Marañon.”

“That’s it! We have conquered him, doubly-conquered!” agreed María Tancreda. “Tonight, he will speak on our radio.”

“Hurray for Don Gregorio!” multiple voices cried. Already some wanted to propose to the Central Committee of the Communist Party that Don Gregorio Marañon be named National Hero of Doctors, Poets, and Peasants. But first, according to widespread opinion, they had to await the return of that jackass Atún with the earlier proposition.

__________________________________

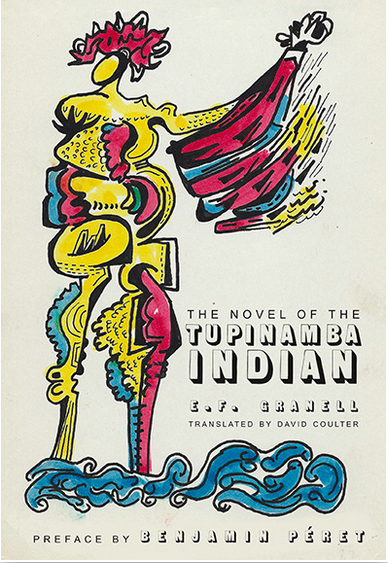

From The Novel of the Tupinamba Indian. Used with permission of City Lights. Copyright © 2017 by E.F. Granell.