Henry and Edith were in north Norfolk, on the second day of their honeymoon. Arriving the day before in the heat of the early afternoon, they had thrown down their bags in the hallway of the rented cottage and gone out walking across the salt marshes, on the banked, coiling paths Edith likened to the leavings of giant sandworms. They both exulted in the place. The landscape was so 8at, a tint of green, yellow, brown printed under a great rectangle of sky, that the trees and houses in the distance seemed only a smudge on the fine line of the horizon; the fields of reeds fanning round them made tidal sounds in the wind, premonitions of the sea. After a mile or two they had taken off their boots, turned orange by the dust, and descended onto the mudflats in bare feet. They sank in up to their shins, the black mud sucking and squeezing, and walked stork-like to the shoreline, washing their legs in an inlet where a small dog was hopping madly, before climbing back onto the path and sitting on a grassy promontory stalled in its rush to the sea. They talked a little, and read their books, and went down to the water, and then walked back to the cottage, stopping for a glass of beer at the inn along the way. They made a small supper, their elbows arguing in the cramped kitchen, and afterwards worked companionably in the sitting room. When it got late, they went to bed. It was, almost, the kind of day they could have had at any other time, in the time before they were married.

So was today. Henry was lying in his shirtsleeves in the garden correcting the proofs of an article he’d written on Whitman. It was a beautiful morning and he had to squint at his pages, against which the intruding blades of grass seemed positively to shine green. He felt tickled by the heat, or the grass; it was a comfortable discomfort, lazily endured. A large tree whispered over the low wall in the warm wind, its branches reaching to touch the stone and then racing away again. Edith was working at the desk in the sitting room—when he looked over his shoulder he could just make her out through the window, her features partly obliterated by great streaks of sunlight, smears of sky and tree on the glass. But he was looking at his proof page, where was printed:

Whitman has made the most earnest, thorough, and successful attempts of modern times to bring the Greek spirit into art. The Greek spirit is the simple, natural, beautiful interpretation of the life of the artist’s own age and people under his own sky, as shown especially in the human body. “If the body were not the soul,” he asks, “what is the soul?” This is Whitman’s naturalism; it is the re-assertion of the Greek attitude on a new and larger foundation. Morality is thus the normal activity of a healthy nature, not the product either of tradition or of rationalism.

He reread this paragraph, wondered about replacing “larger” with “grander,” and then decided against it. Behind him he heard a sound. He rolled onto his hip and turned his head to see Edith pushing out the top window, her small white hand stealing into the sunshine,

Fixing the latch and withdrawing as she sat back down, safely obscure again behind the streaked glass with the restless leaves reflected in it. There was something in the brisk purposefulness of the gesture, in the fact that she hadn’t even looked over, that pleased him. It was one of the things their marriage was intended for: the perpetuation of this sort of oblivious together-working.

Still, there was a twinge under his contentment, reminding, like a splinter he couldn’t work out. It was only as they went upstairs last night that the scale of the silence they had constructed together on the subject of consummation finally became apparent, nearly crushed him with its awful weight and totality. There was the room, with its chest of drawers and wardrobe, into which Edith began placing the things from her case, the mystery going out of them, their intimate connection with her body and personality exposed as a sort of deceit. The bed, on which she periodically perched, was menacingly white. He stood there uncertainly, watching, until he was seized by the realization that he should do the same, hanging up his few shirts and his jacket, folding his spare trousers and his underwear into the drawer she had left for him. Once this was done Edith looked up from where she was sitting on the edge of the bed, and he saw for the

First time a tremor of uncertainty on her face. She looked as though she were nerving herself for a jump.

“Do you think we should undress together?” she said. “There’s downstairs.”

For a moment he struggled to see the angle of her concern. Then he understood that what was at stake was their vaunted openness, their insistence on the simple beauty of the body, threatened now by the supple shynesses and proprieties of their youth, into which he too felt an overwhelming urge to retreat. “I think we should,” he said, fear and excitement constricting his voice.

“Yes, all right,” she replied, not quite holding his eye, beginning concentratedly to loosen her cream-colored cravat and unbutton her blouse; beginning to undo the effect she had made that morning once he was capable of seeing her properly, seated in their compartment as the train began to crawl, the view through the window still showing the security of the station. When she had looked at him, still breathless from their run, her face flushed, and said, “Here we start, Henry.” He turned from her now, not thinking this dishonest, and slowly removed his boots and socks. He wound his watch. He could hear Edith behind him, tutting over something, and then the soft rushing of cloth lifted and allowed to fall. He glanced over to catch her still seated on the bed, her nightdress bunched around her waist; in the seconds before she tugged it down over her legs he saw the plumped cushion of hair, some of it copper in the light from the lamp. She looked back at him, and he knew that he had misused his time: she had nothing to do now but watch him. It seemed impossible to talk: the atmosphere was too heavy with their responsibility to their past selves, the man and woman who had sat fully clothed in brightly lit rooms and bandied around the word “sex.” Edith pushed herself backwards on her palms to the head of the bed and got under the bedclothes. The shadows in the room peeled back a little as the lamp shone out without obstacle. Henry unbuttoned his shirt and took it off. Edith was leaning against the pillows, observing him frankly, somewhat boyish. The light played over the keys of his ribs and he scratched the hair on his chest before fiddling with his trousers. As he stepped out of them, stooping to pull a leg over a heel, he staggered and put a hand out to the wall to steady himself, feeling at that moment more exposed than ever before in his life. But when he stood up in his drawers, Edith’s eyes still on him, the ripple of a smile on her face, he felt himself going helplessly, unexpectedly hard. This experience, standing at the foot of the bed in the silence of the lamplit room, his member ratcheting upwards in small hiccups, with Edith watching him, perhaps watching it—its notations in the fabric of his underwear—was unlike anything he had ever imagined for himself, even in Australia, in that lonely cabin at Kanga Creek. His eyes met Edith’s over the white expanse of bed. Words retreated. There was nothing for it. He seized at the strings to loosen them and pushed his drawers down, his erection bending and springing. He could not look at Edith now—he reached for his nightshirt and pulled it over his head, feeling it catch ludicrously at the front, and advanced to his side of the bed, lowering and collapsing himself into it, stretching out his legs under the cover. His face was hot but the rest of him felt preternaturally cold, so that he rubbed his feet together fiercely.

“Shall I put out the lamp?” Edith said.

The embrace of darkness was welcome, almost warm. He breathed into it, adapting to the unfamiliar dimensions of the bed, the answering weight of a body close by. He could not bring himself to shift to face her, but could see her hands, dark like his, laid over the white cover. His erection, pitched against his shirt, invested Edith’s every breath with significance; he could not believe it existed in such proximity to her, to a woman, could not bear now for something not to happen to it. “Edith.” It came out in a parched gasp, so that he cleared his throat and repeated it: “Edith.” He had the idea of the word being swallowed up by the darkness, disappearing into it like food into a child’s mouth.

She did not answer. He did not want her to. She rolled onto her side; her right hand reached across—he shivered as it passed over him—took his, and brought it between her legs. Their joined hands traveled under her nightdress into the space between, grazed by hair; then her hand was guiding his fingers into an enveloping warmth, wet. Her fingertips were on his knuckles, pushing; he let himself be directed, pushed, until he picked up the rhythm. Her breath was close on his cheeks. He was breathing heavily too, as though they were exhausting each other.

“Now.” She said it urgently, on an outward breath, rolling onto her back.

Henry moved with her, barely conscious of his actions, compelled by something other than himself. He found he was still hard and got himself onto his knees at her side. He remembered they hadn’t kissed and leaned over where he thought he could see her mouth, finding instead the side of her nose. She didn’t appear to notice, putting a hand on his ribs and lifting her legs, shifting him so that he was in front of her. Still feeling strangely like a spectator of his own behavior, Henry gathered up his shirt around his waist and then, thinking better of it, dragged it over his head, casting it off into the darkness. He could see Edith a little better, the shape of her defined by the hazy gray of her nightdress. But she suddenly seemed quiet, passive, tense with waiting: he realized they had reached the limits of her knowledge. His senses pinching into alarm, the air picking at his nakedness, he nudged her nightdress up over her stomach, soft beneath his fingers, wanting but not daring to reveal her breasts. He shuffled forward on his knees, the sheet bunching under them and making him clumsy, and leaned into the gap between her legs, bracing his arms at either side of her head. Her face was under his now, but she looked past him, over his shoulder; her eyes closed and opened, she was breathing very quietly through her nose. He didn’t know what to do; his cock was almost 8at on top of her, her hair tickling it, and his arms were already beginning to hurt. It was ridiculous, to have attended births, to be able to name constituent parts, but to be so ignorant of technique, so unmanned by the dark. He hesitated to discern her body with his hands. “Open your legs,” he whispered, hoping it would become obvious. She did, wider, and he backed away a little, pulling himself onto his elbows, feeling panicked as she turned her chin up to him. He pushed forward hopefully from his hips, felt his cock skim over her inner thigh, into a mesh of hair. The contact was so thrilling that he wasn’t immediately embarrassed. He tried again, adjusting his position, and this time felt himself within the ambit of that surrendering warmth—though he seemed to travel somewhere across or above it. Edith lay prone beneath him, eyes glittering in the dark. Sweat prickled at the beginning of his buttocks; his arms ached. Heat was spreading up over his back, across his shoulders. He went once more, thrusting it forward like an unwanted offering, the sheet slipping treacherously under his knees: again it was misdirected. In response Edith shifted, slightly, as if in sleep, though he could see her expression in the speckled dark, the crease of worry in it, a sort of fixed concern—and his panic seemed to slow, to coagulate in his mind: no thought, no action could form in it. The heat washed rapidly along the full length of him and he felt his cock slacken, dip and drop, stagger into softness.

It happened with such instantaneousness that this too seemed some inevitable working out of physiological destiny, a further, ultimate abnegation of control. He remained staked on his elbows, wishing himself out of his body. It took a moment for Edith to realize what had happened. She pushed down her nightdress like a shutter. A hand spread on his chest. “Dear boy,” she said.

The sun was seeping into him. His eyes were closed and he was lying on his back, a finger pinned to the right page in his Whitman proofs. All he could hear was the tree’s whispering, the rustle and scrape of its returns and retractions. He and Edith had not yet made reference to last night—the sunlight already pouring into the room when they woke had seemed to question the reality of what had taken place in the darkness. And their nightclothes had all the warm, safe sleepiness of childhood on them. Would the coming of the evening make it unavoidable again? He felt ill-served—by his body, by his understanding, by Whitman even. For he did not want to go back to the bed, to the dark. Old certainties rode rampant in his mind, coldly trampling the newer: he would never perform the act, it was not in his nature; what was in his nature was not communicable, it narrowed to him alone. And yet, still it was wonderful, to feel the heat of the sun pushing idly through his senses, to think of Edith working in the sitting room, behind the glass. They were married. In some way, perhaps, the worst of the anxiety had lifted. They had faced experience together. Edith did not seem angry or concerned. He thought of the way her hand had stolen out into the sunlight. Marriage brought with it the possibility of permanence, permanent possibility. The tree rustled and scraped in the bright world beyond his eyelids.

He must have fallen asleep. For Edith was above him; a blackish shape knocking its head against the sky. And behind this shape another. He brought a hand to shadow his eyes.

“Call this work, Henry Ellis?”

He sat up, hot and oddly dizzy, his proofs sliding off his chest and sprawling in his lap.

Edith smiled down at him. As did the woman standing behind her.

“Henry, this is Miss Britell. She lives a little over yonder and stopped by to say hello.”

“Very nice to meet you, Miss Britell.”

“And you, Mr. Ellis.”

Edith looked between them happily: Henry still squinting up from the grass, Miss Britell in an extraordinary green dress, covered with printed sunflowers. “I thought we might go for a walk,” she said.

__________________________________

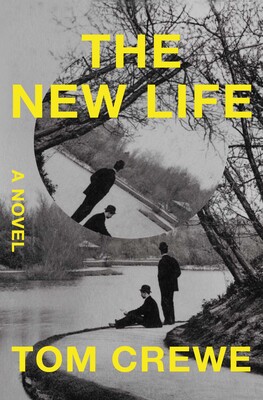

From The New Life by Tom Crewe. Used with permission of the publisher, Scribner. Copyright © 2023 by Tom Crewe.