The Necessity of Return: On Years of Ritual Killings in Nigeria

Adedayo Agarau Describes the Trauma of Returning to the Street He Grew Up On

In a dream on one of my first nights in Iowa, I was weeping into a river. The river was flowing swiftly, washing away many people. In the logic of the dream, I knew their faces—they were the same children who once dribbled past me on the dusty streets of our childhood. How were they grown if they had died in the first years of the taking? When I woke up, I cried into my hands in the small room of the apartment I shared with Tyler in Coralville, Iowa, and for the first time, I felt the sharp sting of survivor’s guilt.

I wrote the first poem in my collection on my flight out of Nigeria. A sudden flood of childhood memories had left me gasping for air, as if from tachypnea. The dust of Ogunleye, the crooked end of the street, the large canal by my uncle’s shop, the small stream of water that flowed behind our house into the large canal at the other end of the street, the foul smell that overcame the street the first time, the getting used to, the boys. The boys of my childhood. Throughout my MFA at Iowa and my fellowship at Stanford, I folded my traumatic childhood into odes and elegies. Four years later, as I was editing the collection, the past began to pull at me again.

When the bones of memory rise inside you and the birds of home arrive at your door, you will carry your bag and leave. I had been invited to two weddings: my best friend, Kosemani, was marrying her talented drummer lover, and my cousin, Tobiloba Adeyemi, was finally marrying his childhood sweetheart. I hadn’t told anyone I was coming. While Tobi and Kosemani are both incredibly important to me, the real reason I had to go back was simpler: I needed to walk again, as an adult, through the long stretch of houses on Ogunleye Street—the street of my trauma, the street that took and took until the cries of children began to sound like vultures.

I was four years old when I first witnessed a kidnapping.

I considered the logic of my decision to go to Nigeria without informing my family. I knew my parents were always in front of their TVs. They must have seen the daily news reports, the tally of kidnappings and murders that justified their fear. On December 4th, my father’s birthday, I called the family WhatsApp group and announced that I was heading to Canada for a writers’ retreat to spend a few days with Salawu Olajide, a Nigerian poet and scholar living there. I wasn’t yet brave enough to tell them I was heading to Nigeria. How do you tell your migrant parents you are returning to the country they ran from—not just for weddings, but to take your professional headshot in front of the house where they birthed you?

I knew about trauma—I had read about it, heard people talk about it—but I didn’t recognize my own trauma until I left Nigeria. I didn’t know the body could be its own agent, that it decided the past had been too much, and then, simply, break down. How unfortunate it is to come from a place that does not allow you to feel. My family doctor in Iowa, during my first major depressive episode in America, asked if I had ever been treated for depression. She asked about my past. Asked if I could define my trauma. I couldn’t. It would not make sense if I tried.

How could I explain a memory that was not a single story, but a flash of color, a sound, a feeling? I was four years old when I first witnessed a kidnapping. The details that remained were the reckless arrival of the yellow and brown minibus as our long line of schoolchildren filed down NTC Road, marching toward the YMCA for Sports Friday. My school shared the field with other primary schools, so the procession was a long mix of uniforms, hundreds of children led by their teachers. The sepia of memory still has not mitigated the fear I felt when hefty men jumped out of the bus, loaded a score of children into it, and zoomed away. The chaos that followed.

We clapped when the plane landed in MMA. I hurried, like everyone else, to grab my hand luggage from the overhead bin and joined the long line of impatient returnees. We were many, and we all looked like we had been deprived of the misfortune of home—as if we had all returned from safety into necessary chaos. You learn the rules quickly. The officers scrutinize you, especially if you’re young, until you squeeze a few notes into their palm. Then they sing your praises.

My sister met me at baggage claim, pressing folded naira notes into my palm. The customs officer smiled and said, your madam na very good woman o, concluding she was my partner. She had done the rites of passage.

The automatic doors of the arrival terminal slid open, and a wall of familiar heat hit me. My sister and I loaded my bags into the trunk without needing to say much—the shared look of relief was enough. In the car, my sister navigated the chaotic Lagos traffic while I watched the city go by. The silence between us felt heavy, so I filled it with the horrors I’d read on Nairaland—stories of ritual murder that confirmed nothing in the city had changed.

I knelt by the canal and wept into my hands, letting the grief swallow me.

In the years leading up to the general election in 1999, my parents locked us in the house—the one-bedroom apartment on Ogunleye Street where my elder sister and I were born—because children were being kidnapped for money rituals. The elders on the streets said democracy was coming and they needed blood to fortify their powers. On such afternoons, my sister and I played hide and seek. I would hide under the bed, and she would find me. We would hear our neighbors’ children playing in the backyard and sometimes in the rain. Through the netted window, we watched the sun sinking into the blouse of sky, counting the number of birds that perched on the clotheslines. Years later, in therapy, it came to light that my fear of small spaces is because this body that was kept alive in those small rooms is finally admitting its own trauma.

We pulled into my uncle’s compound, and the gatekeeper, a man I’d known since I was a boy, broke into a wide grin. “Ah, Oga, you are back!” he shouted. That was the moment it felt real. I was home. The next day, I drove to Ibadan with my photographer friend, Victor Olatunji, and we went straight to Ogunleye Street. The afternoon sun licked the windscreen of the car, and the heat boiled my skin.

I pointed to the dried river that overlooked the house. We swam there as children until the day we found Teslim floating limbless—the boy who taught us to swim, missing for weeks. When we saw him, we screamed like a chorus. The dried river is now a canal where people dump their refuse. I knelt by the canal and wept into my hands, letting the grief swallow me.

Unlike our final days living here, the street was alive with children returning from school, a band of boys already flying their kites, and some in the corner of the street, near the canal, were playing soccer. Victor and I joined them briefly, giggling as they watched us juggling the ball. The afternoons of those years wore gold like jewelry, and the sun kissed our skin as dust rose behind us in small clouds that the wind. Our kites pulled against our hands, as if trying to lift us into the eyes of God.

A woman burst from a tiny shop, the fashion posters on her wall fluttering in her wake. She screamed her child’s name—“Adeeeeeee!” Like the clang of bells, the sound bypassed my ears and punched the air from my lungs. It was the sound a throat makes at its most desperate—a long, tearing vowel trying to pull a life back from an empty sky. Then, a memory detonated. A mother, one evening, staggered onto our street. Her voice shredded as she screamed the names of her four children, one after another, clawing at the air as if she could pull them from it. She threw her body against the pavement beside Iya Dele’s shop, performing the frantic theatre of loss. Her children had left for school that morning. All four of them. They never made it home. My father, in the company of the committee of fathers, carried her when she fainted by the gutter and bathed her with buckets of water. When she became conscious, she had become too weak to name her children, so she mumbled incoherently. A man, I recall, whispered that she was going mad.

The street I knew operated on multiple temporalities—at the break of dawn, mothers held their children’s wrists tightly as they walked them to school, while the birds broke the first light with music, and the men opened their shops. Some women hung their laundry behind their houses, and daughters served their fathers by reading newspapers on wooden benches outside their houses. The evenings were dotted by us. We were loud even as we played catch under the floodlights pouring into Ogunleye Street from Liberty Stadium.

And when kidnapping started happening and our parents worried for our safety, and we stopped frequenting school because the ritualists started targeting children returning from school, the wind swirled alone outside, and we heard the whistles. The sun lit the sky, scorched the roofs, but there were no longer shadows of boys running shirtless down the streets. Our shadow did not form, for months, on the walls of houses—we did not watch it gesturing as we giggled. For months, we did not break car windscreens or our neighbor’s louvers because we were safely tucked away in our fathers’ houses.

The years slowly moved away from us, its silence uncanny, but the smell of carcasses was unfathomable.

At night, while our parents made dinner, we listened to crickets and frogs make the dark their orchestra. I read Ralia the Sugar Girl, straining my eyes under dim lamps. I watched the candlelights dance, flames escaping through the window, collected by the winds outside. I had several dreams of my father folding me gently into his breast pocket, but I did not know what it meant. What does it mean to fold your child into your breast pocket? The years slowly moved away from us, its silence uncanny, but the smell of carcasses was unfathomable.

When Taofeek was taken from us in 1999, his school uniform, bag, and shoes were discovered by what was then an uncompleted building. The house is now painted yellow, and there are tenants. I asked myself if this is how a house becomes haunted. A woman, whom I assumed was a tenant, was outside sorting melon seeds. She sat on a kitchen stool in the shade of the building, deshelling with her learned hands, winnowing the chaff. Taofeek was my classmate at Bodma International School. We had a crush on the same girl. The last time I saw him was the day he stole the letter I had handwritten for her and presented it as his. That was the day they took him from us, and although he lived several streets away, they found his items in the building across from our house.

I finally stood in front of my house and introduced myself to the new occupants. “I was born here,” I declared shyly to the woman who had a shop full of candies and biscuits. Her shop had replaced Iya Dele’s shop. Dele, as I recall, was the best dribbler in our age group. He was thin, and when he ran, the winds carried him. When he was kidnapped and his limbs harvested, we didn’t know what else to call his mother, so we kept calling her Iya Dele. We kept redressing her wound, reminding her what she had lost, what she could never find whole, even if the river returned her son’s body.

I could not tell the woman about my trauma on this street. I met her children, one of whom attends Ibadan Boys High School. The woman asked me why I had come back from America to visit, and I lied that I just wanted to see what it looked like again. I wanted to, but most importantly, I wanted to finally stand on the street of my own fear of disappearance. I wanted to show myself why I could no longer get into any large body of water to swim. To piece together the cursed memory and tell my dead band of boys that I am finally remembering and writing about them. I asked the woman if I could take a photo. And when she asked why I wanted one, I said, “I am writing a book about this place.” I have written a book about this place.

Victor set me in front of the veranda, and asked me to smile. I formed a slight, cursive smile and let a tear fall. I hadn’t felt a tear fall down my face since 2023, since I have been heavily medicated for anxiety and depression. The thoughts of my mother, the day I went missing, arrived. Perhaps the dreams were finally revealing their intentions—a child in his father’s breast pocket is his father’s child. That day, my father took a bus ride to visit my grandfather, a high priest in Ijebu Igbo. When, later, I asked him what happened, he said “wèrè la fín wo wèrè,” that is, we use madness to cure madness.

__________________________________

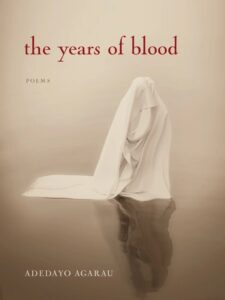

The Years of Blood by Adedayo Agarau is available from Fordham University Press.

Adedayo Agarau

Adedayo Agarau’s debut collection, The Years of Blood, won the Poetic Justice Institute Editor’s Prize for BIPOC Writers (Fordham University Press, Fall 2025). He is a Wallace Stegner Fellow ‘25, a Cave Canem Fellow and a 2024 Ruth Lilly-Rosenberg Fellowship finalist. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Agbowó Magazine: A Journal of African Literature and Art and a Poetry Reviews Editor for The Rumpus. He is the author of the chapbooks Origin of Name (African Poetry Book Fund, 2020) and The Arrival of Rain (Vegetarian Alcoholic Press, 2020).