Cal’s daughter was always telling him what he could and couldn’t say. She kept reminding him that he was retired—unlike every single one of her friends’ fathers—therefore unacceptably old, therefore doddering around in a kind of anachronistic limbo that was deeply mortifying for those forced to live in close proximity to him. One thing he wasn’t allowed to do, she’d informed him, was to say that his tenant had a silly name. Rain was his name.

“How is that spelled?” Cal asked, when he met with Rain’s wife to have her sign the lease. He couldn’t remember the wife’s name because he’d been so bowled over, when they met, by the fact that her husband’s name was Rain.

“Rain,” said the wife. “R-A-I-N.”

“Like rain from the sky,” said Cal.

“Yes,” agreed the wife.

Cal thought she looked a bit embarrassed.

Cal had never met Rain. In July the couple moved into the tiny post-war house he owned (bought in 1989 for $30,000 and now with a market value, everyone kept shrieking at him, of at least $300,000). Rain had just been hired by the political science department at the university, and was never home. Cal only ever dealt with the wife.

“She’s a stay-at-home wife?” demanded his daughter, Terry.

“Yes,” said Cal. This new term: stay-at-home wife. How was it different from housewife? Who had found it necessary to make the change? This was something else he was not allowed to say.

“But she must do some kind of work,” insisted Terry.

“Well, I don’t know,” said Cal. “Maybe she’s looking.”

He stood up from the table to find the HP Sauce and paused to pet his daughter’s head a couple of times. He didn’t know how else to show affection anymore. Anyway, it was instinctive with him. Her hair was so straight and smooth; it invited hands. Sometimes, petting her head, he would sigh dreamily, “I wish we had a dog,” and leap out of reach as Terry whirled to punch him. Soon she would move away from home. She wanted to go to an elite arts college in Montana to study dance. The only reason he’d held on to the house near the university for so long was so that she could live in it while she attended school in the city.

“Whatareya gonna do with the house?” everybody slobbered at him. Big money! Big payoff! To own property that close to the university was, this past year, like sitting in your backyard and having the ground suddenly start to rumble and spew oil like on The Beverly Hillbillies. It was a city of Beverly Hillbillies lately—everyone cashing in. But Terry still could change her mind. Surely someone out there—not him, but someone at school, some adult she actually looked up to, her band teacher maybe—would talk her out of studying dance. He’d made the mistake of calling it dancing once, in front of some relatives who’d been passing through town. “Terry thinks she’d like to study dancing.” The thinks had been bad enough. Calling it dancing, however, he still hadn’t lived down.

Cal had a knack for tenants. As a rule, he didn’t rent to undergraduates. Not that he had the instinctive loathing and distrust of them that some of his property-owning neighbours did, but just because he knew that if he wanted to keep the place in decent shape for Terry, he couldn’t have kids in their early twenties living there. He rented to graduate students—most often couples—or sessional instructors, or new professors like Rain. People in training for home ownership and the middle class. Good tenants appreciated reasonable rent at a time when everyone living near the university was being milked like cattle, so when they moved out they recommended equally good tenants, who would appreciate it in turn. If you treated people fairly, they returned the favour. You didn’t just gouge people because you could—because it happened to be the thing to do.

Cal would never forget his first landlord. He’d gone up north on a construction job and rented a basement from one of the managers. The manager had stipulated no smoking and no drinking.

“Fine,” said Cal.

“No visitors,” added the manager about a month after Cal had moved in.

“Pardon?” said Cal.

“No visitors.”

“Oh, okay,” said Cal, who didn’t know anybody anyway.

“No music,” added the landlord shortly thereafter.

“I’m sorry,” said Cal. “Was I playing the radio too loud? I can turn it down.”

“No,” said the landlord. “You don’t turn it down. You turn it off.”

Three months into the rental, Cal realized he was brooding about the landlord almost every waking moment. Whispering outraged comments to himself on his way down the hill to the site, gritting his teeth over the circular saw, breaking into a frustrated sweat at the thought of going home in the evenings.

I hate going home, he kept thinking to himself. He has made it so I can’t stand to go home.

So Cal started staying out.

“No staying out past ten,” the landlord said to him one morning when Cal was on his way down the walk.

Cal stopped and turned around. The landlord was standing by his Honda, key in hand. He had offered to drive Cal to work every morning, but Cal had made excuses about enjoying the walk—the site was just down the hill. It was what had made the rental so attractive in the first place.

Cal walked over and stood on the other side of the landlord’s Honda as if he had changed his mind about the drive and was about to climb into the passenger’s side.

“Pardon?” he said.

“No staying out past ten,” repeated the landlord. “We can’t have you waking us up at all hours.”

“That’s ridiculous,” said Cal.

“Well, that’s the rule, I’m afraid.”

“You can’t treat people like this,” said Cal. His armpits blasted sudden heat.

The landlord looked astonished. “I own this property,” he told Cal, gesturing at the house behind him. “This is my property.”

The way he made these statements—as if they were even pertinent, as if they answered for everything—stayed with Cal for years. When Cal built his own home—and then, on a whim, purchased the house near the university—he made a vow to himself with his first landlord in mind.

“I’m here to pull some snow off the roof,” he said to Rain’s wife.

“You’re here to . . . ?” she repeated, looking worried.

I should have called first, thought Cal. “I’m sorry,” he said, “I should have called. It’s just that it’s not good for all that snow to be piled up there.”

“Oh!” said Rain’s wife. Now she looked guilty.

“It’s my job to look after this sort of thing,” Cal assured her. It wasn’t really. But Rain and his wife, Cal knew, were from somewhere unspeakably cruel, considering the deep-freeze they had moved to. Santa Cruz, California. Terry had been excited by this. It was the reason she wouldn’t leave him alone about the tenants. That magic word: California.

So Rain and his wife couldn’t be expected to understand the culture of cold and all it required. Moments ago when he approached the house, for example, he’d almost dislocated a hip slipping on a frozen sediment of snow that had caked up on the second step. They hadn’t shovelled, and there had been some melt, and the snow had solidified into ice.

“Maybe I’ll just clear your steps for you while I’m here,” said Cal.

“Oh,” said Rain’s wife a second time. “You don’t have to do that.”

“Well,” said Cal, and stopped himself from finishing: somebody does. “You could hurt yourself.”

Cal asked her about the salt and the chipper in the basement, and once it was clear she had no idea what he was talking about, he asked if he could retrieve them himself. She backed into the foyer, saying, “Of course, of course.” Californians, thought Cal, bending over to pull off his Sorels. You’d think Californians would be—I don’t know. More sure of themselves. Rain’s wife seemed so timid and deferential. Terry would be disappointed, to say the least. He took off his boots in the foyer and saw there was no mat nearby. Salt and grit from previous outings had discoloured the hardwood floor.

“Cal,” said Rain’s wife. “Now that you’re here, could you do me a favour? Could you check out the furnace?”

Cal stood there noticing two things simultaneously. The floor was cold. It was so cold, the chill was already seeping through his thermal socks. And Rain’s wife was wearing a fleece jacket over a thick wool sweater. As Cal registered this, she wiped her nose—twitchy and pink, like a rat’s—on the sleeve of it.

He picked up his boots and carried them with him to the basement.

It was only when he returned to deliver the space heater that she told him Rain had gone. He was leaning over, after plugging the thing in, holding his hand in front of it to make sure it worked. She leaned over to do the same. They stood there, leaning together, feeling for heat.

“There it is,” said Cal after a moment. He wiggled his fingers. “It doesn’t feel like much right now, but these things are great. We used to use them on construction sites.”

“It’s just,” said Rain’s wife, “that Rain is gone.”

Cal straightened up a bit creakily. His hands went to the small of his back. Rain’s wife was rubbing her nose on her sleeve again.

“He’s not here?”

“You’re—” said Rain’s wife. “I’ve been meaning to tell you. I mean, you’re the landlord. It’s just me living here now.”

“Oh, I see,” said Cal.

He drove home troubled.

“About how old is she, Dad?” Terry wanted to know.

Cal guessed about thirty-five, unaware of the trap he’d just stepped into.

“Thirty-five, Dad? A thirty-five-year-old girl?”

Cal rolled his eyes. He mentioned that Rain’s wife had struck him as “a nice girl.” This was something else he couldn’t say.

“Well, what’s she going to do?” asked his wife, Lana, as Terry guffawed over her spaghetti. “Is she moving out?”

“She didn’t say,” said Cal. “She just said she’s by herself now.”

“What happened to the husband?”

“I don’t—Terry, will you stop?” Terry was making a big production of pounding her fist on the table, convulsed with mirth. She was at the age where she took everything too far. Actually, it seemed to Cal that she should have passed through this phase long ago.

It snowed again and didn’t stop for three days. He thought of her, alone in the house. He picked up his address book and dialled the number he’d scrawled beneath the word Rain.

“Hello there,” he said when she picked up. He was calling her “there” because he didn’t know her name. “It’s Cal. How are you getting along in all the snow?”

“Oh,” she said, “I keep thinking I should shovel, but there doesn’t seem to be any point!”

You should shovel anyway, thought Cal. The neighbours. And she seemed to have no idea it was also her responsibility to clear the sidewalk in front of the house. But he said, “No, I know. It’s, ah—it seems like an, an exercise in futility.”

“That’s exactly it,” she said. “It’s like an insult.”

“Insult to injury,” replied Cal.

“Yes,” she answered faintly.

Cal pictured her rubbing her twitchy rodent’s nose on the sleeve of her fleece, saying, It’s just me now.

“Not like California!” he crowed, suddenly hearty.

She laughed like a sob down the wire.

Terry, home from school because of the snow and still in pajamas at two in the afternoon, stood in the living room window watching him plow the walk on his ride-on. Then he trundled down the sidewalk, clearing that, and finally cleared the walks of the neighbours on either side. It took no time at all and was an easy enough courtesy.

“You looked so happy,” Terry told him when he came in. “You looked like you would’ve cleared every driveway on the block if you could get away with it. That’s so sad, Dad. You are such a sad, sad man.” She flounced away with her hot chocolate.

When the snow stopped, he loaded his plow into the back of the truck, drove north toward the university and thanked God for four-wheel drive when he turned onto the apocalyptic side streets. City hall was being bombarded with complaints, because it contracted snow removal out to private companies, and the private companies answered to no one. They were too busy, they claimed. There was the Costco parking lot to be cleared, the Best Buy. Cal bounced over Himalayas of ice and packed drifts. Past buried cars. It was like with construction these days—too much work, too few companies. There were always bigger, more lucrative jobs. Workmen tore holes in people’s walls, went away, and never returned.

What was the good of all this money? If it made no one responsible to anyone else? If it made life not easier, but in some cases impossible? He thought this as he pulled up to the non-existent sidewalk of Rain’s wife’s house; buried, like everything, in snow. There she stood, up to her kneecaps in it, stabbing wildly at the second step with the ice chipper. It made an awful, echoing clang every time it hit concrete. When it didn’t hit concrete, when it just bounced uselessly off the unyielding ice, it made an unsatisfying thuck. The sound of her helplessness dully resonating. Another insult.

The furnace man had not come. Cal was incredulous.

“You’re kidding.”

“They’re probably so busy this time of year.”

“Yes but—Jesus Christ,” said Cal. “I called three weeks ago.”

“The space heater works fine,” she assured him.

Cal frowned at it. She was responsible for the electricity bill. It would be through the roof by month’s end.

“Listen, dear,” he said. Terry would castrate him for calling a grown woman “dear,” but he had to call her something. “Take a hundred dollars off the rent this month.”

She blinked at him. She was wearing the same fleece over a thick turtleneck. Over the fleece she had draped the knitted throw that, during his last visit, had adorned her shabby ottoman. The ottoman, he noticed, was nowhere in sight. The place was only semi-furnished now. Rain had subtracted his things, presumably, and the room stood half nude, throwing weird echoes now that there was less furniture to absorb human voices.

“Cal,” she said, softly, because she wasn’t so stupid as to dig in her heels about the rent. “There’s no—”

“No, no,” he shouted, causing her to cringe a little. He just wanted the conversation with its hollow echoes to end. “It’s absurd. It’s just absurd,” he said. And went outside to finish de-icing her step, forgetting to say goodbye. Then he changed the blade on his snowplow and annihilated the layers of tramped-down snow that had caked up where the sidewalk used to be.

He sat in his truck and took out his phone in order to yell at the furnace man—a man he knew, a man named Mike—but all he got was a recorded, vaguely seductive female voice, which informed him Mike’s inbox was full.

He looked up at the house and Rain’s wife was staring out her window at him, just standing there, not looking off or turning away as he gazed back, as if she wasn’t aware she was doing it.

“Why don’t you go home?” he said out loud.

The wife was a web consultant, she’d mentioned back in July. What did that mean? Terry had told him that anything having to do with the internet meant pornography. The only people who made any money via the internet, she said, were pornographers. They were legitimate business people now, she proclaimed, not sleazy pervert types. They had BlackBerrys and took meetings and it was good business, just like anything, just like oil and gas. Some of them were even women. (Oh good, thought Cal. Terry is considering this. This is her fallback if dancing doesn’t work out.)

So Cal could only assume that Rain’s wife made no money. He imagined her work as a “web consultant” to be one of those nominal jobs that stay-at-home wives sometimes had. A job that wasn’t actually meant to furnish any income other than what his mother used to call “pin money.” That was why she didn’t go back to California. Rain’s wife was trapped.

“Terry is too confident,” Cal told Lana one night.

Lana laughed at him.

“I don’t think you understand,” he persisted. He wasn’t sure how to approach this with her. It required laying out the kind of home truths women seldom liked to hear.

“Confidence is good, Cal. We want our daughter confident.”

Lana had stopped speaking to her own father at the age of twenty-five. She didn’t know he had died until a couple of weeks afterward, because her mother had long since passed, and her other sister didn’t speak to him either. And when she did find out, Lana gave no indication that she cared. Lana’s father had terrorized and oppressed both daughters every day of their lives. They couldn’t date, they couldn’t go out, they had to come home immediately after school, they would not be sent to college because college was the place where women behaved like sluts.

“We will not be doing that to our daughter,” Lana told Cal, often.

So Cal had been terrorized in turn with the idea that if he ever spoke a word of reproach to any of the females of his household, their mouths would snap shut and they would saunter out from under his roof, leaving him to age in silence, to decompose in an empty house.

“She takes certain things for granted,” Cal persisted.

“Like what?”

“Like her safety. She’s sheltered, she’s protected. She’s lived a comfortable life, and she thinks she’s invulnerable.”

“Well, let her think it.”

“No,” said Cal. “She’ll be going to Montana, or wherever, next year. She knows nothing about it. The world is a dangerous place. What about all those street women who were murdered?”

“What we do is,” smirked Lana, “we take precautions. We discourage the use of crystal meth, for example. I think we should take a hard line on that.”

At that point, Cal climbed out of bed and put on his bathrobe all in one motion.

“Cal,” said Lana, startled.

“I’m not a fool,” said Cal.

His daughter wrestling with him when she was little, angry that he could so effortlessly break out of her grip. She wanted him to pretend that she was stronger than he was, and he of course had obliged, bemused but also a little horrified. The blithe way women took the gentleness of men for granted. The kindness of strangers. Early in his marriage to Lana, he’d been stunned to realize how different their perception of sex was. While he was ever aware of how protective, how careful he was being with her, it seemed she never was. This amazed and troubled him, because for Cal, the restraint was part of the sweetness. He could have been rough with her, could have grabbed her and pushed her and maybe she would have even liked it, but he never did. It didn’t seem to occur to Lana that things could be any other way. This was the stunner: she didn’t even know. My dear, he wanted to say to his daughter sometimes, if a two-hundred-pound man wants to drag you into an alley, he will drag you into an alley. It won’t matter how well you do in school or how assertive you are with telemarketers. It won’t matter how many times you correct an old man for calling a woman a “girl.” You’re still going into that alley. It is an ugly thing to think, and to say, but there you go.

“MIKE,” CAL SAID to the furnace man. “Five weeks now, Mike.”

“You have no idea of our workload right now, Cal.”

“This is north,” said Cal. “It’s February. People could freeze to death. Senior citizens living by themselves . . .”

“No one’s freezing to death, Cal,” said Mike. “My God. Just get her a space heater, you’re the landlord.”

“You are . . . an asshole, Mike,” Cal stuttered.

He’d never said this to another man before, and he’d never hung up on anyone. It enraged him that he didn’t know how to fix a furnace in his own house. If he proposed to have people living under his roof, wasn’t it incumbent upon him to ensure that the necessities of life, such as warmth in the wintertime, were provided? Money wasn’t enough. That was the mistake men always made—assuming money was enough. To think that he could end up the kind of man who was helpless without money, who wasn’t able to just do it himself if he couldn’t pay someone else to do it, made him sick. Because that wasn’t a man. That was just another kind of asshole.

It went to forty below.

When he arrived, she was outside, flailing away at the sidewalk. She wore her hood up and a toque pulled down over her eyebrows, and a voluminous cotton scarf wrapped around everything but her eyes. She looked like one of those veiled women from the Middle East, except puffed out by her down coat, and with a gargantuan head. Nothing visible but squinting eyes. Crisp white clouds plumed from beneath the scarf and hung in the air like solid objects.

“I love this,” she said to Cal as he approached. She had figured out how to use the chipper. She lodged it beneath a layer of ice and then threw her weight upon it and an enormous wedge of the ice layer broke off and came free of the sidewalk.

Cal understood her satisfaction immediately—force overcoming resistance, over and over again. He surveyed her work. She’d cleared the entire walk and had done about a foot of sidewalk. But it was a big lot. There were hours of work ahead of her, which he doubted she would finish by sunset.

“That must’ve taken you all day,” he said.

“It did,” she said. “I thought I would hate it, but I love it. It’s therapeutic.”

“But, dear,” he said. “This temperature—you’re making it too hard on yourself. Better to wait until it warms up a bit.”

“I can’t,” she told him. “I got a note from the city this morning.”

This broke Cal’s heart and enraged him all at once. The city—the city who would not even clear the street—had left a note in the mailbox of his house, demanding he live up to his most basic responsibilities as a homeowner.

“And the mailman left a note too,” she added. “He stopped delivering the mail.”

Mail-person. Letter carrier. Postal worker. She had no idea what she was doing to Cal.

“I’m so sorry,” he fretted. “About the furnace. I just don’t know when the guy’ll be out.”

“Oh—” She pulled down her cotton scarf a little to wipe the condensation off her face, and he could almost feel the moisture freezing his own cheeks. “The space heater’s fine. And I started cooking roasts! I never cooked roasts before. I used to be a vegetarian.”

Cal could only stare at her.

“It heats up the kitchen,” she explained. “Cooking roasts.”

He had an image of her huddled in front of the space heater amongst her bare-bones furniture, gnawing away at a glistening slab of pork butt. Instead of dropping to his knees before her on the patch of sidewalk she’d managed to unearth, he turned and made for his truck.

“Call me,” he yelled without turning his head. “Just call me if you need anything.”

He did not phone to check up on her for well over a month. He had never avoided anyone out of shame before.

Then spring happened, the way it sometimes does in extreme climates. That is, it broke wildly over the city like a piñata. Sun and heat blazed down and suddenly there were rivers of melt in the streets. A new kind of chaos took over as the city overflowed. Cal knew his own basement would be fine, because he had built it himself. But he wondered about hers. He hadn’t been to her basement since he went down to get the salt and chipper—months ago. He tried to remember if she had anything important-looking stored down there. If she’s having any trouble, he told himself, she’ll call. And she didn’t.

Terry would graduate in a few months. They still hadn’t heard back from Montana, but he had persuaded her to apply to the local university as a fail-safe, and she’d been accepted.

“Whatever,” Terry had said, refolding the acceptance letter.

“Whatever,” repeated Cal. “I’m getting one of the best educations in the country. I get an entire house to live in for free—whatever. Tuition has gone up another twenty percent and my education is bought and paid for. Whatever.”

Lana, who had been putting away groceries with her usual impatient rush, glanced over and started moving in slow motion as if he’d pulled a gun.

“All right, Dad,” said Terry, rising so as not to be in the same room with him anymore.

Rents in the city had skyrocketed in the past year. A basement “studio” for twelve hundred dollars. He’d read a piece in the paper that said five Chinese exchange students had been discovered living practically stacked on top of one another in such a place. Fire hazard, said the city. The landlord denied any wrongdoing and was contesting it. These people gotta live somewhere, he told the reporters.

Cal started fantasizing about calling Rain’s wife in June and telling her she had to move out by the summer because Terry needed to move in for school. It started out as a kind of masochism, taking root in his guilt and dread. But he kept coming back to the scenario, rehearsing it a little too compulsively, and after a while it became almost pleasurable to contemplate. He imagined her helpless, flailing silence.

But Cal, she would stammer at last. I don’t have any money.

Not my problem, I’m afraid.

I don’t know anybody here. Wherever shall I go? Whatever shall I do?

Frankly, my dear . . .

Please, Cal. I’m begging you.

I’m sorry, Rain’s wife. (No, he wouldn’t even say he was sorry. He didn’t have to say that.) I can’t help you, Rain’s wife. There’s nothing I can do for you. Absolutely nothing. You have one month. To get out. To get the hell out. To hell with you.

Then, as if she had heard all this—as if the shameful echoes in his head had somehow transmitted themselves to her—she called.

“It’s Angie,” she said.

“What?” said Cal, even though he’d recognized her voice at once.

“Angie. At the house?”

“Oh, yes. Hi, Angie,” said Cal.

“How are you?” she said.

“I’m fine, dear,” said Cal. “Everything okay?”

“All of a sudden,” she said, laughing a little, “it’s so warm!”

“I know,” he said. “Strange weather.”

“I see there’s an air conditioner in the basement.”

It was too early for an air conditioner. And not nearly hot enough to justify one. She was supposed to be from California.

“Oh dear,” he said. “You have to understand about the weather here. We’re just as likely to get another snowstorm next month.”

She laughed again like he was kidding. “I was going to fire it up,” she said. “But then I realized the storm windows were still up.”

“Honestly, dear,” he said, “I’d keep them up for a while yet.” And how did she suppose she was going to get the air conditioner up the stairs herself?

“It’s just so warm,” she persisted. “And I can’t really open the windows to get a cross breeze.”

“Right,” he said. “Well, I could come by.”

“Would you?”

“Of course,” he said.

But he put it off for over a week. Then she called again.

Cal apologized. He’d been very busy. His daughter’s graduation coming up. Lots of activity. To his surprise, the fine weather hadn’t abated. He had supposed the temperature would drop again and she would see the wisdom of putting off the storm windows for later in the season. He told her he would stop by as soon as he had a moment. She was grateful. But he didn’t go until the following Wednesday, and he didn’t call to tell her he was coming.

“Oh no,” he yelped at the sight of them. “No, no, no!”

Angie and a man were in the yard, struggling to remove one of the storm windows from its hooks at the top of the frame. It had come free of one hook, but they were having trouble with the other, so the entire five-by-three-foot pane was dangling by one corner. The man had barely the arm-span to manage it. They had dragged the picnic table, of all things, over to the side of the house and the man was standing on it, on his tiptoes, stretching to his very last inch in the attempt to hoist the window free of the hook. He didn’t have the height or the strength for this. His T-shirt rode up and Cal registered a queasy contrast of black hair against white belly, the hair thickening considerably as it approached his crotch. This could only be Rain.

Angie stood on the ground beside him, ineffectually reaching up to steady the window.

It seemed only Cal was aware that the moment the thing came free of the hook, it would fall backwards, shattering on top of both their heads. Rain, face blank with exertion, glanced over as Cal scrambled up onto the table to take charge.

“Let’s get it back up there,” said Cal, grabbing a side. “Get it back on the other hook so you can take a rest.”

Rain grunted in agreement and the two of them managed to reattach the other corner.

“This is Cal,” Angie said from somewhere behind him.

Standing together on the brutalized, corpse-yellow lawn, the men shook hands.

“Rain,” said Rain. He was wearing a sports jacket and black basketball sneakers. His T-shirt said Talk Nerdy to Me. His bushy head of hair, unlike the hair on his belly, was almost completely grey.

This was a professor, Cal reminded himself. At the university. The university had hired him to teach students political science. Would Terry be taking political science? Rain tried not to pant, his grey mop soaked in sweat. Cal wondered how long the two of them had struggled with the window. The thought of them like that—Rain helpless with the oversized pane, Angie helpless on the ground beside him, both about to be grated like cheddar—made his bowels flutter.

“Rain,” repeated Cal, and the name was like a mouthful of spoiled food. “Listen, that window might be rusted onto the hook up there. You just leave it to me. I’ll get a stepladder and—” at this point, had he been talking to Angie, Cal would have stopped himself—“do it properly.”

“Yeah,” agreed Rain. “Thanks, bro. Seriously. Angie says you’ve been great.”

“Oh,” said Cal, flustered by a near-irresistible urge to shove Rain as hard as he was physically capable of doing.

“So I should get going,” said Rain.

“I’d like a word with you,” said Cal.

Angie went inside the house and the two of them stood in the alleyway together. Cal had no idea what he would say, he only knew he wanted to talk at this man. He felt it like a sudden, stabbing hunger, when you know you’ll eat whatever’s put in front of you. He opened his mouth and listened to himself as he would an authoritative voice on the radio.

“You have abandoned this girl,” Cal heard himself saying. “This is Abandonment.” He said it over and over again, hearing the capital A in his voice, as if he were charging Rain with a crime—wanting to impress upon him the seriousness of his transgression. Rain stood with his hands on his hips, gazing at the ground and shaking his head. Sometimes he shook it tightly, as if in defiance, and other times loosely, in apparent disbelief. Cal realized with disgust that Rain was never going to raise his head and look him in the eye.

At the same time, Cal knew men left women and women left men and it was all perfectly legal—even natural. It was a tragedy, but only in the way that all of nature was a tragedy. But there were rules, there were truths and virtues, and that was all he wanted Rain to acknowledge.

The question was, what if Rain didn’t know? This is what kept Cal talking, fast and mindless, in a voice that sounded abraded and high-pitched, like Angie’s chipper scraping concrete. What if Rain, who continued to stand there and shake his head with loose, angry amusement, who was from Santa Cruz, who merely wanted someone to talk nerdy to him—what if Rain had no idea what Cal was talking about? What if Rain was oblivious? What if Rain—who should have been laughable, and who instead made no one laugh—what if Rain, himself, laughed?

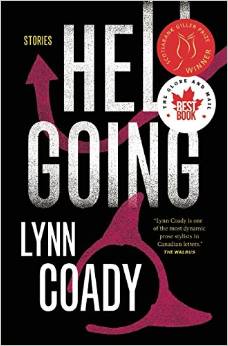

From HELLGOING. Used with the permission of the publisher, House of Anansi Press. Copyright © 2015 by Lynn Coady.