A rainy, early spring day in Gloucester, Massachusetts. The whole town seems to be holding its breath for the tourist season, just about to begin. For months the town has sheltered in place through the winter, like any seaside town—half the houses empty, the businesses with reduced hours. Any weekend now, though, the tourists will be back, breathing life once more into Cape Ann.

Down on Cressy Beach, on a shoal of rocks beneath a promontory, there is a mural of the sea serpent. On a large boulder that marks the end of the beach, a long, loosely coiled creature that looks a bit like the ampersand on the Dungeons and Dragons logo. It has four stubby legs, each with ferocious claws, and a long jaw and red sliver of a tongue.

Robert Stephenson had only graduated from high school when he painted the beast in 1955, before joining the Army. After he retired, he returned to Gloucester and formally began his training as a painter, and became a local fixture until his death in 2013. Stephenson’s sea serpent mural, likewise, has become a fixture of the community, perhaps more so than the monster itself.

And truth be told, it looks very little like the descriptions recorded during that 1817 summer, whose dominating feature was the humps rising out of the water. This serpent, its long body spilling onto itself like a pile of rigging, lacks that simple elegance—though it has its own dragonlike charm.

No one here wants to talk about the sea serpent. The docent at the Maritime Museum has heard about it, of course—everyone has—but it’s just some local legend. It doesn’t mean anything. At two different bookstores I stop into, nobody knows much about the sea serpent, but they both point me to the book Wayne Soini’s The Gloucester Sea Serpent. It is everywhere books are sold. It seems to be all Gloucester wants to say about their sea serpent.

Soini refers to the botched taxonomy job by the New England Linnaean Society as a “flop”: “because a Loblolly Cove snake distracted and confused” the committee, they “lost their chance at scientific acclaim.” The story of the sea serpent has become a story of a committee duped by a rickety snake and the limitations of taxonomy.

But the sea serpent’s tale is more than just a failure, and any serious discussion of cryptozoology should have the Gloucester sea serpent front and center. It may not have the pull of Nessie, or Bigfoot, or even Lake Champlain’s Champ. It doesn’t even have a diminutive nickname. It’s just the sea serpent. But it is, I think it’s fair to say, special.

Most cryptid sightings are one‐on‐one occurrences: someone alone at night, on a backcountry road or in an isolated woods. Sometimes it’s a small group. Maybe there’s a fuzzy photograph, but soon enough the creature vanishes, never to return. But the Gloucester sea serpent was different. Scores of people saw it—people came from all over, gathered on the shore to gawk, and there it was.

Visible from shore or from a boat, exactly as expected. Different people on different days, all independently, all with more or less the same basic descriptions. No other cryptid in the long history of such beasts can boast such visibility—not Bigfoot, not Nessie.

Whatever it was, it was not a hoax or a hallucination. The Gloucester sea serpent faded from memory because the New England Linnaean Society got it wrong, creating a new species based on a snake plagued by rickets. When their error was exposed, the original sightings, it seems, were forgotten. But while Jacob Bigelow’s analysis of the rickety snake disproved the holotype specimen, Bigelow didn’t disprove the sightings themselves. The people who saw the sea serpent all agreed it was much bigger than a normal snake anyway.

The sightings defy all of the modern tropes for cryptid sightings, and yet the sea serpent has none of the cachet that other cryptids do. It seems possible, a rationalist could argue, that it was an oar fish, or some other animal that’s since been cataloged. It would be impossible to know for sure, of course, since we have nothing but those eyewitness reports. But this is as good a story as cryptozoologists are likely to find, in terms of the preponderance of evidence. Why doesn’t it get more love? Two hundred miles north of here, there might be an answer.

Loren Coleman’s International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine, remains the hub for all things Sasquatch and Nessie, as it has since 2003. It’s moved locations over the years, but is now situated in a relatively new development called Thompson’s Point—there’s a wine bar and a taco joint, and a pretty busy brunch spot, along with an adjacent concert venue.

It feels like one of those shopping/nightlife destinations that hasn’t quite materialized yet. Inside, the narrow museum doesn’t occupy much square footage, but is crammed to the gills with stuff. The Jersey Devil, New England’s water monsters, and all manner of Wild Men are represented here.

If a Bigfoot—or a sea serpent, or a giant bird, or Nessie—is really out there, there’s simply no excuse anymore for not being able to get a good, clear video of the dang thing.Disappointingly, though, a good deal of the exhibits are pop culture ephemera—action figures, lunch boxes, movie posters—which tend to overwhelm the newspaper clippings and other “evidence.” At times it feels like one is in a comic‐book store rather than a museum—there are a few cast footprints and grainy photos here and there, but it’s best not to visit the International Cryptozoology Museum hoping to be convinced by the preponderance of documentation.

That doesn’t mean that Coleman himself isn’t serious about his work. Indeed, Coleman is the last of a long legacy—he got interested in cryptozoology in his teens, and now is the last living remnant of that earlier age of heroic adventurers like Tom Slick, who plunged into the wilderness in hopes of glory.

He’s published dozens of books on cryptozoology, and while his writings often veer toward the speculative, he nonetheless has maintained credibility as residing on the scientific end of cryptozoology. In a disreputable field, Coleman remains among the most reputable.

I’ve come to the Third Annual International Cryptozoology Conference to see where the future of monster hunting lies. There are a good fifty or so attendees this Labor Day weekend; more than you can find at some other venues, but less so than you might expect. The vendors’ tables are a bit sparse—not more than two dozen in all. If this was once a major destination, it is no longer. During the breaks between the talks, a surf rock band obliterates any chance of conversation, their riffs echoing through the open hall, ricocheting off the concrete and steel at deafening levels.

The logo of the conference this year is a giant panda. Thought by zoologists in the West to be mythical until 1869, its story mirrors that of the mascot of the Cryptozoology Museum itself: Latimeria chalumnae, the coelacanth. When Marjorie Courtenay‐Latimer, curator of the East London Museum in South Africa, discovered one in a sherman’s trawling net in 1938, the animal had long been presumed extinct—the fossil record indicated it had last been seen on Earth some 70 million years ago.

Coelacanths and pandas are enticing mascots for cryptozoology, because they remind us that the animal kingdom still holds mystery for us, and there are still creatures—even large, charismatic megafauna—that might be waiting to be found. But they also raise problems, precisely because their circumstances are so different from most cryptid stories. Rather than a blurry photograph or a dubious eyewitness account, the coelacanth appeared in the 20th century as a corpse, an actual specimen that could be studied, documented, preserved.

Once scientists went looking for more, they found them. Any potential for a hoax was dispelled as more and more specimens were retrieved, including living specimens, and the animal was documented on film. In other words, unlike cryptids, the panda and the coelacanth refused to remain hidden.

The talks at the conference seem almost of a different time. They don’t break much new ground: there’s a short film on the Florida skunk ape, a talk on the Beast of Gévauden, and a lecture by Dawn Prince‐Hughes titled “Songs of the Ape People.” Most of the speakers rely on the same data set that cryptozoologists have been working for decades: eyewitness accounts, interpolated folklore, occasionally a bent tree or a weird‐looking footprint, and some blurry photographs.

Then Todd Disotell gets up. A primatologist at Columbia University, he’s a popular figure in the cryptozoology world because, in addition to being a gregarious speaker and all‐around genial guy, he seems more willing than many of his colleagues to take amateur cryptozoologists seriously. In 2014, he cohosted the reality show 10 Million Dollar Bigfoot Bounty, in which Bigfoot hunters sought evidence of the cryptid’s existence that would stand up to scientific scrutiny. (None did.)

Still, the audience is friendly toward Disotell, who shares their sense of adventure and their love of the undiscovered. He starts by discussing the Tapanuli orangutan, an extremely rare species that lives in a single forest in Sumatra; only in the past ten years was this species identified as distinct from other orangutans, and though their numbers are small (critically endangered, their population is estimated at 800), they are nonetheless a newly discovered species. In other words, Disotell tells the audience that there are still unknown primates waiting to be found. We haven’t fully exhausted the world’s largesse.

But it’s also a not so subtle rebuke of the way Bigfoot hunters continue to go about their work. Building to an exasperated crescendo, Disotell tells the audience, “Stop sending me hair samples and grainy photographs!” If Bigfoot hunters want to be taken seriously, he exclaims, they need quality video, a body (or at least a body part), a live specimen. Plaster casts of footprints simply won’t cut it.

What Disotell’s talk makes plain is that the tried‐and‐true methods of documentation among cryptozoologists—footprint casts, blurry photographs, lone eyewitness accounts, shaky video—are not only unacceptable as proof of a new species, but increasingly anachronistic in a world of high‐definition cell‐phone cameras. If a Bigfoot—or a sea serpent, or a giant bird, or Nessie—is really out there, there’s simply no excuse anymore for not being able to get a good, clear video of the dang thing.

Cryptozoology, in many ways, seems stuck at an impasse—mainstream science has repeatedly evaluated the kinds of evidence that cryptozoologists have offered, and rejected it as insufficient. Cryptozoologists, meanwhile, have doubled down.

How do you bring together the antiscience cryptid hunters with folks like Disotell, who are trying to remain open‐minded while continuing to insist on some kind of actual evidence? The fact remains that there are new species being discovered every day, things that would in another context easily fall under the heading of cryptozoology, and yet these things remain outside the sphere of interest for cryptid enthusiasts.

At the same time, those things proffered by Sasquatch hunters as incontrovertible evidence remain uninteresting for scientists, precisely because they’re anything but incontrovertible. The two communities remain at odds, talking past each other.

Meanwhile, a new creature has been seen stalking the woods of North America. Dogman gets described in multiple ways: either as a canine‐looking creature walking upright or a Bigfoot type with an elongated snout. Though Dogman believers claim that evidence of the creature may go back to ancient Egypt (the dog‐faced god Anubis, some claim, is actually a literal cryptid), in the cryptid lore it’s a far more recent development.

Most contemporary Dogman legends can be traced back to a Michigan DJ, Steve Cook of WTCM‐FM in Traverse City. For April Fool’s Day 1987, Cook recorded a song about the Dogman called “The Legend,” basing it on Native American accounts he’d come across.

Cook received calls from listeners who’d claimed to actually have seen the thing, and after an appearance in 2010 on an episode of MonsterQuest, the Dogman broke out of Michigan and began to appear throughout North America.

It’s described as significantly more dangerous than Bigfoot—whereas the latter is a gentle, silent, solitary figure, Dogman seems threatening and aggressive. A report from Broome County, New York, collected on the website Dogman Encounters, comes from a woman who came home with her two children to an eerie silence, creeping her out and prompting her to grab her children and bolt for the door.

While she fumbled to get her house key in the door, she heard a low growl coming from her left: “As the growl continued,” she recounted, “it seemed to melt into audible words, spoken in a very deep and gruff tone, that seemed to have a rough sort of reverberation quality to them. What I heard as clear as day was, ‘You can’t get in.’ The only word that I’m unsure of is the first, ‘You,’ as the sound of growl transitioned to English words and it sounded more like ‘Yyyyhhh.’”

Until I started talking to contemporary cryptozoologists, I’d never heard of Dogman before—it doesn’t show up in the traditional accounts and doesn’t have the storied history of a water monster or the Jersey Devil. But Dogman’s popularity is on the rise these days. For Blake Smith, cohost of the skeptic podcast MonsterTalk, it’s a noteworthy shift, because, as he notes, “There is no evolutionary basis for bipedal canids and the whole Dogman thing feels a lot more like a supernatural or magical (or folklore) type of event.”

Descriptions of a menacing gure that can speak English certainly departs far from the standard cryptid description, and Dogman’s rising popularity suggests that cryptozoology may be veering toward what Smith calls “magical and ultraterrestrial thinking” in cryptozoology.

“I see that as bad for anybody who wants to really bag one of these things for scientific study because it’s hard enough to get people with scientific credentials interested in doing eldwork around cryptids. Nobody’s getting grant money to study werewolves—which is basically what Dogman seems to be.”

The Dogman appears to blend into the supernatural rather than merely the untaxonomized. It is as if the impasse that defined cryptozoology—between the blue‐collar adventurers and the would‐be scientists—has finally given way; those who now pronounce the Dogman as a viable cryptid are no longer seeking to prove science. They’re now closer to paranormal investigators than scientists. This is a shame for those hanging on and trying to do serious scientific work outside the academy, but it’s also possible that this may be for the best—particularly if you look at someone like Henry H. Bauer.

“A belief in the reality of Nessies is not harmful,” Bauer wrote in 1986 in his book The Enigma of Loch Ness. Bauer, who at the time was a professor of chemistry at Virginia Tech and would go on to be the dean of its College of Arts and Sciences, worked hard in his early career to distinguish between harmless speculation and dangerous conspiracy.

Questions of “quackery in medical matters (psychic surgery, extreme forms of faith healing, laetrile, and so forth) or of cults led by fanatics or impostors,” are one thing, he notes, but belief “in cryptozoological phenomena—Loch Ness monsters, sea serpents, Bigfoot, Mokele‐Mbembe (dinosaurs in Africa)—seems to me singularly harmless.”

The further divorced cryptozoology becomes from science, perhaps the less likely it will be to actively disrupt scientific consensus.But the problem with fringe beliefs is that often one conspiracy begets another: once you’ve decided that the consensus is wrong about a given arena of scientific knowledge, it’s easier to cast suspicion on other consensus beliefs as well, and once you’ve made the choice to doubt mainstream science, it can be hard to pick and choose which orthodoxies to discard.

It’s true that Bauer’s interest in Nessiedom is itself fairly harmless (as is the interest of anyone else who spends their days taking sonar readings in the Loch), but since he began his fascination with the mysterious water beast, Bauer has himself ventured into murkier waters. After retiring from Virginia Tech, Bauer became the editor of the Journal of Scientific Exploration, which focused on various fringe studies, including paranormal activity, UFOs, ESP, and so forth.

Under Bauer’s direction the journal also began to publish pseudoscientific critiques of AIDS research, and Bauer ultimately published his own AIDS denialist hypothesis. Though Bauer has never done any research on AIDS or HIV, his book became a major citation by AIDS denialists, who used it to bolster their unfounded claims that “many of the epidemiological aspects of HIV . . . are literally incompatible with the hypothesis that it causes AIDS.” Bauer’s credentials and his ability to mimic the pose and rhetoric of serious scholarship while not engaging in any direct research on AIDS have had a devastating effect.

In Loch Ness Bauer found what he perceived to be the arrogance of the scientific edifice: “The Loch Ness affair well illustrates, I believe, some general and important aspects of the interaction of science with the wider society; for example, that science generally dismisses (at first, at least) claims by laymen of unusual events, phenomena, or theories; that outsiders can rarely induce scientists to take such things seriously; and that the interested observer finds it difficult to make sense of the ensuing argument and to reach a reasonable judgment.”

It didn’t matter that this was an institution that he himself had once been a part of as a notable chemist; the refusal of mainstream science to take the possibility of Nessie seriously was a glaring act of hubris, one that cast into doubt much of scientific orthodoxy.

“To find a circumstantially made case compelling,” Bauer admits, “one must be prepared to see coherence, a pattern of relationship, among phenomena that are not incontrovertibly related.” Taking as his truth the existence of Nessie forced an entirely new mode of inquiry, one based on circumstantial evidence and blurred photographs, one that required discounting the scientific method and ignoring the absence of evidence. Once down that road, Bauer was prone to allow his homophobic views to guide his skepticism toward the AIDS narrative, to the detriment of science.

So long as fringe belief is engaged with mainstream, institutionalized science, there is a tension that threatens to spill over past shadowy water creatures and bipedal apes. The further divorced cryptozoology becomes from science, perhaps the less likely it will be to actively disrupt scientific consensus.

It’s not that there aren’t cryptids out there to be found—but they won’t be mythical monsters. The Gloucester sea serpent has lost its fascination for us because it’s been bested by even weirder things we’ve since found in the ocean: deep‐sea isopods, colossal squids, feathered lobsters—things that are beautiful and strange but that still belong in the realms of taxonomy.

These creatures do not exist for our own symbolic matrix. Just as geologic evidence of the real “Lemuria” has little to do with the mythical civilizations of Lemuria, the new species discovered constantly by scientists have no symbolic meaning for ourselves, as the natural world once did.

Our disappointment with the natural world has to do with the fact that it no longer serves to reflect back our values and fears to us. Moving away from cryptids involves more than just a reaffirmation of objective science and verifiable evidence—it will take reconceptualizing the world away from a sense that Man and his God are at the center of all things, and that all things exist to reflect us back to ourselves.

__________________________________

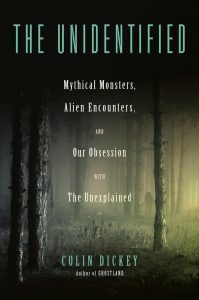

From The Unidentified by Colin Dickey, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2020 by Colin Dickey.