The Monster That Drew Crowds to a Small Midwestern Town

Let Us Now Hear the Tale of the Hodag

Case File #7: The Hodag (1893–present)

Name: The Hodag

Scientific Name: Defies Classification

Location: Rhinelander, Wisconsin

Description: Approximately 185 pounds and seven feet long, a cross between a lizard and an ox complete with razor-sharp fangs and horns. The creature is said to have glowing green eyes and smoke curling from his nostrils. Early versions of the Hodag described the beast as black; later his color changed to a friendlier green.

Witness testimony: “This is not a wood carving we are talking about, but a beast with the power to rip the belly out of the biggest bear, needle-sharp horns on the end of his tail, glowing green eyes and flaring red nostrils and a smell that would drive a skunk off a gut pile, remember? Those eyes and nostrils would send the biggest, meanest lumberjack running for his mommy, long before the horns, claws, and tail points would come into play.” –Jerry Shidell, 2017

Conclusion: The legend lives. The creature . . . not so much.

*

We have come to see the Hodag and we won’t be turned away.

“Come on,” my five-year-old son calls to me, “hurry up or we’ll miss it.” How do I tell him that we can’t miss it? That it’s impossible to miss something that doesn’t even exist? Nonetheless, I quicken my pace (“I’m coming, I’m coming”), weaving through dozens of other Oneida County fairgoers in an effort to catch a glimpse of the most horrible creature the region’s ever known.

Welcome to Rhinelander, Wisconsin—home of the Hodag. The town makes no secret of their monster; in fact, they’ve embraced it fully, as evidenced by the enormous Hodag statue displayed just outside the chamber of commerce.

But we’ve journeyed here today, not for any statue, but for the “real thing.” Or as real as a fake thing can be.

Just ahead of us on the makeshift stage, Jerry Shidell (playing the part of 19th-century Hodag originator Gene Shepard) works the crowd with his huckster’s charm.

“Step right up, folks! In eight and a half minutes the Hodag show will begin. That’s right! In eight and a half minutes you will see a real, live Hodag!”

“Like . . . the actual monster?” my son asks, wide-eyed.

“I mean, that’s what the guy says . . .” I shrug.

Jerry (or should I say Gene?) smiles as the other children in the crowd begin asking similar questions of their own parents—How big is it? How bad is it? Is it hungry? Jerry returns his attention to his partner, Junior, who straightens his lumberjack hat as he prepares for the role of a lifetime: introducing fairgoers to the Hodag itself.

Mythic as he is mysterious, dangerous as he is discrete, the Hodag (allegedly) sits tethered just behind a curtain within the tent.

Eight and a half minutes later, we anxiously await the show to begin. “You ready?” Jerry whispers.

Junior nods.

“Then here goes nothing . . .”

A cleared throat, followed by: “Greetings! Now then, who’s here to see the Hodag?”

We in the crowd surge forward, anxious for a spot inside the tent. The stale air mixes with the heat, producing a distinctly human smell: not quite body odor but close, the olfactory equivalent of anticipation, perhaps, or the pungency of fear.

“Surely by now most of you know the Hodag story,” Jerry begins, and though we do, he takes advantage of his captive audience to tell it again. We stand at rapt attention as he recounts every detail of the harrowing story—the hunt, its capture, as well as Gene Shepard’s heroic role in taming the beast.

“And now, without further ado,” Jerry concludes, his voice turning to a whisper, “Junior and I look forward to introducing you to . . . the antediluvian creature itself!”

Jerry gives Junior the nod, signaling his young assistant to move behind the white screen and reach for the bungee-cord leash (allegedly) attached to the Hodag.

Junior gives it a pull, and the beast’s silhouette pulls back.

We chuckle as Junior’s launched forward, struggling to stay on his feet. “Try it again,” Jerry coaxes, though when Junior does, he’s met with a warning growl, prompting him to drop the leash and run for cover. “Oh, come on now,” Jerry prods, “give the people what they want, Junior! And they want to see the Hodag. Am I right, folks?”

The Hodag—much like Paul Bunyan—managed to extend beyond the confines of the bunkhouses, reaching into the world of popular culture as well.

“Yeah!” we holler. “Show us the Hodag! Come on, Junior!”

At our coaxing, Junior takes one last crack at pulling the Hodag into view, stepping behind the screen once more to fight the silhouette.

Another growl, and then, chaos: hollers and screams and a cloud of chicken feathers wafting through the air.

“Shepard, I need some help!” Junior cries, his face momentarily visible over the lip of the screen. “I need . . .”

Suddenly a razor-sharp claw reaches above the screen, pulling Junior back down while their silhouettes offer a dramatic, visual play-by-play.

We watch in jaw-dropped horror as Junior at last escapes from the Hodag’s clutches, hurling himself back in front of the screen, his shirt in tatters.

Jerry scratches his head before offering his preplanned apology. “Well I’m sorry folks, but . . . we’re just not going to be able to show him today. It’s very unsafe for us to bring him out. Again, I’m sorry. The exit’s to your left.”

“Aw, man!” my son says. “We didn’t even get to see him!” Grumbling, we all make our way toward the tent flap as Jerry and Junior share the briefest of smiles.

“I guess that means we’ll have to come back next year,” I say. Which, of course, is exactly the point.

*

One hundred twenty-four years after its “discovery,” the Hodag remains as alive and well as ever. By which I mean: not alive and well at all. But at least its story remains alive and well, and some of the credit goes to 69-year-old actor, entrepreneur, and former Rhinelander mayor Jerry Shidell, who, year after year, faithfully plays Gene Shepard in the Oneida County Fair reenactments. Though the original Hodag story will always belong to Shepard, who in addition to being a successful timber cruiser, was a bit of an actor and entrepreneur himself.

As the story goes, one October afternoon in 1893, 39-year-old Gene Shepard was strolling among the pine and hemlock trees when he stumbled upon an unknown creature skulking in the woods near Rhinelander. He could hardly believe his eyes: the black beast resembled a cross between a lizard and an ox, complete with razor-sharp fangs and horns, not to mention the fire and smoke smoldering from his nostrils.

The creature weighed in at 185 pounds and was about seven feet long. Shepard froze at the mere sight of it, his eyes drifting across its spiky back as the creature’s glowing green eyes stared back at him. As horrible as it was to view, it was equally horrible to smell, its stench described by Shepard as “a combination of buzzard meat and skunk perfume.”

Startled, Shepard made his retreat into town, where he rallied the finest hunters, returning to the location to take the beast dead or alive. Upon their approach, the hunting dogs were soon torn to shreds, at which point the hunters opened fire to little avail. Desperate, they turned to their dynamite sticks, hurling them at the creature, who absorbed the blasts until catching fire and smoldering to death—but only after nine horrific hours of thrashing.

Or so one version of the story goes.

There are plenty of others, all of which serve as fine contributions to late 19th- and early 20th-century lumber camp lore. But the Hodag—much like Paul Bunyan—managed to extend beyond the confines of the bunkhouses, reaching into the world of popular culture as well. Stories were big business, or had the potential to be, and in 1896, when Gene Shepard learned that Rhinelander’s Oneida County Fair had no major draw, he took it upon himself to rectify the situation. He’d already concocted the Hodag story a few years prior; now, all he needed was the Hodag itself.

Retreating to his barn, Shepard began carving a creature befitting his tale.

I can’t help but envision this moment as the North Woods’ equivalent ofFrankenstein: the mad-with-power Shepard cobbling his creature to life as lightning blazes overhead. Reaching for his tools, he carves fangs, inserts horns, and tests the sharpness of each spike with his fingertips.

Once he’d carved the beast, Shepard needed only to revise his tale, offering a version that didn’t end with the Hodag burned to ash as he’d previously recounted. He was more than up to the task. In the days leading up to the fair, Shepard publicized his revised version of the Hodag’s “capture” by way of a front page article in the local newspaper.

In this version, a group of lumbermen were wandering the banks near Lake Creek when they came upon the Hodag holed up in his den. Well aware that the creature could never be overpowered by strength alone, they relied on their wits instead. Dousing a cloth in chloroform, they slid it onto the end of a long stick and pushed it within sniffing range of the Hodag’s snout. The chloroform did its work, downing the beast long enough for the men to restrain it. At which point the lumbermen did the logical thing: placed it in a wagon, transported it to Rhinelander, then housed it in a pit for safekeeping.

In the opening days of the fair, Shepard welcomed visitors into a tent to catch a glimpse of the beast. And, indeed, a glimpse was all he offered them. Mindful that the mystery is often better than the reveal, Shepard did his part to create the conditions to ensure that his Hodag remained conveniently out of sight. He held onlookers to a safe distance, kept the lights low, and allowed visitors only the briefest, neck-craning peek.

“To further convince the spectators,” writes Hodag scholar Kurt Kortenhof, “Shepard’s sons manipulated the bogus animal through a system of hidden wires.”

One of those sons was Layton Shepard, who for years continued to play a supporting role in his father’s ruse.

“[Dad] was just an expert of leading these people into a certain state and then scaring them half to death,” Layton recalled years later.

It didn’t hurt that the people of Rhinelander wanted to believe—at least in the beginning. After all, what town doesn’t want to be home to a monster? Or anything, for that matter, that had the power to make it unique?

__________________________________

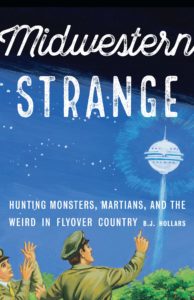

Excerpted from Midwestern Strange: Hunting Monsters, Martians, and the Weird in Flyover Country by B. J. Hollars by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. ©2019 by B. J. Hollars.

B.J. Hollars

B. J. Hollars is an associate professor of English at the University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire. He is the author of The Road South: Personal Stories of the Freedom Riders, Flock Together: A Love Affair with Extinct Birds (Nebraska, 2017), and From the Mouths of Dogs: What Our Pets Teach Us about Life, Death, and Being Human (Nebraska, 2015).