The Moment When Punk Collided With Poetry

On the Rock 'n' Roll Art of Patti Smith, Sam Shepard, and More

Patti Smith began pivoting from Off-Off-Broadway to poetry and rock ‘n’ roll around the time she befriended playwright and drummer Sam Shepard. They first met after a Holy Modal Rounders show downstairs at the Village Gate, where Shepard had previously worked as a busboy. Smith was planning to write about the Rounders for the rock magazine Crawdaddy, but as Shepard’s bandmate Peter Stampfel said, “As soon as she saw Sam she forgot about the article. They took up with each other right off the bat.”

“It was like being at an Arabian hoedown with a band of psychedelic hillbillies;” Smith recalled, describing seeing the Holy Modal Rounders in action. “I fixed on the drummer, who seemed as if he was on the lam and had slid behind the drums while the cops looked elsewhere.” Near the end of the set Smith was struck by Shepard’s song “Blind Rage,” which he sang: Stampfel described it as a “power-punkish number;” with lines such as “I’m gonna get my gun/ Shoot ’em and run.” Smith told biographer Victor Bockris that Shepard’s “whole life moves on rhythms. He’s a drummer. I mean, everything about Sam is so beautiful and has to do with rhythm. That’s why Sam and I so successfully collaborated.”

When Smith met Shepard, he had recently married 19-year-old actress O-Lan Jones at St. Mark’s Church, home of Theatre Genesis. The ceremony was filled with poetry, music, and purple tabs of acid distributed by some members of the Holy Modal Rounders, the wedding band, which also worked with Shepard on many of his shows. Melodrama Play, performed at La MaMa in May 1967, was the first of a series of Shepard’s rock-infused plays, followed by several more over the next few years.

After Melodrama Play, Shepard began incorporating Holy Modal Rounders songs into his plays whenever possible, particularly in Operation Sidewinder. It was his most elaborate and sprawling work, addressing the failures of a counterculture that was increasingly in disarray at the end of the 1960s. “We were out in California at the time,” Stampfel recalled, “and Sam was writing Operation Sidewinder. He thought that a lot of the scenes really tied to a lot of the songs that the Rounders were doing so he put them in the play.” Written in 1968, it debuted at the Vivian Beaumont Repertory Theater at Lincoln Center in March 1970 with the Holy Modal Rounders performing the music. The uptown setting was not a good fit, and Shepard was disappointed with the way the show was cast and with the director’s decision to concentrate on spectacle. “The first time he came to rehearsal, he hated it so much he left,” Stampfel said. “When he came back a few days later, he hated it even more, so he never came back.”

Shepard met Smith not long after Operation Sidewinder‘s debut, though at the time she had no idea that the Holy Modal Rounders’ drummer was a celebrated playwright. She didn’t even know his real name—he told Smith it was “Slim Shadow”—and when they began their love affair, she also didn’t know that he had a wife and child. On one occasion early in their romance, Shepard asked Smith if she liked the lobster at Max’s Kansas City, and she admitted that she never had tried it. After living off of Max’s free bowls of chickpeas, she jumped at the chance to have this mysterious Slim Shadow fellow buy her a fancy lobster meal (two South African lobster tails cost $2.95 at Max’s back then, a luxury far beyond the reach of many back room inhabitants).

As they ate, Smith noticed Jackie Curtis giving her hand signals from another table and assumed she wanted some of their food. Smith wrapped some lobster meat in a napkin and met Curtis in the ladies’ room, where she was interrogated.

“What are you doing with Sam Shepard?”

“Sam Shepard?” Smith said. “Oh no, this guy’s name is Slim.”

“Honey, don’t you know who he is?”

“He’s the drummer for the Holy Modal Rounders.”

“He’s the biggest playwright Off-Broadway. He had a play at Lincoln Center. He won five Obies!”

Smith said that this revelation was like a plot twist in a Judy Garland-Mickey Rooney musical. By this point, she and Robert Mapplethorpe had moved out of the Chelsea and were living across the street on 23rd Street in an apartment that gave them more space to pursue their art (he was focusing more on photography, and Smith continued to create visual art and write poetry). She was happy to return to the Chelsea after Shepard began living at the hotel, where they spent hours in his room reading, talking, or just sitting in silence. During this time, Smith wrote two sets of lyrics for songs that Shepard used in his play Mad Dog Blues, and they also began to collaborate on a one-act, Cowboy Mouth.

“After Melodrama Play, Shepard began incorporating Holy Modal Rounders songs into his plays whenever possible, particularly in Operation Sidewinder. It was his most elaborate and sprawling work, addressing the failures of a counterculture that was increasingly in disarray at the end of the 1960s.”

One evening Shepard brought his typewriter to the bed and said, “Let’s write a play.” He proceeded to type, beginning with a description of Smith’s room across the street: “Seedy wallpaper with pictures of cowboys peeling off the wall” described the stage notes. “Photographs of Hank Williams and Jimmie Rodgers. Stuffed dolls, crucifixes. License plates from Southern states nailed to the wall. Travel poster of Panama. A funky set of drums to one side of the stage. An electric guitar and amplifier on the other side. Rum, beer, white lightning, Sears catalogue.”

Shepard introduced his own character, Slim Shadow—”a cat who looks like a coyote, dressed in scruffy red”—and he then gave her the typewriter and said, “You’re on, Patti Lee.” Smith called her character Cavale. “The characters were ourselves,” she recalled, “and we encoded our love, imagination, and indiscretions in Cowboy Mouth.”

Theatre Genesis playwright and director Anthony Barsha first met Smith when she and Shepard performed Cowboy Mouth on the same bill as Back Bog Beast Bait, which starred James Hall and Shepard’s estranged wife. “It was pretty crazy.” said Hall. “He cast his own wife in a play that was followed by a one-act about his affair with Patti.” Barsha, who directed Back Bog Beast Bait confirmed that it was a complete debacle—though he acknowledged that Cowboy Mouth itself was quite stunning “Their chemistry was like Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor,” he said. “It was an excellent performance, Patti and Sam. It was a treat to see. It’s too bad it had to end abruptly.”

Cowboy Mouth opened and closed at the American Place Theatre on West 46th Street at the end of April 1971. “Patti and Sam’s thinly disguised characters’ relationship was destined to end.” Hall recalled, “just like what really happened between them. Then we found out that Sam had disappeared, and even Patti didn’t know where he went.” Shepard found the emotional strain too much like being in an aquarium,” he later said—so he fled to a Holy Modal Rounders college gig in Vermont. Like his character in Cowboy Mouth, Shepard returned to his family and responsibilities; meanwhile, Smith set off on new adventures.

Around this time, Smith met her future musical collaborator Lenny Kaye at a downtown record store. After playing in garage bands during the second half of the 1960s, he was working at Village Oldies while also freelancing as a music writer. “You work in a record store, you’re surrounded by music,” Kaye explained, “and then you think, ‘Hey, it’s not unreasonable for me to try to make that music and be one of a hundred million records that we’re selling here.’ It makes it less mysterious in a certain way, and gives you a sense that you could perhaps participate.”

“Those older records also provided me with the way that I met Patti,” he added, “because I wrote an article about those songs for Jazz and Pop magazine around 1970.” Kaye’s article spoke to Smith about her own youth, when boys would gather to harmonize on doo-wop songs in southern New Jersey. She called him up and began dropping by Village Oldies, which sold vintage 45 rpm singles. “I’d play some of our favorite records—”‘My Hero’ by the Blue Notes, and ‘Today’s the Day’ by Maureen Gray, and the Dovells’ ‘Bristol Stomp’,” Kaye said, “and Patti and I would just sit around and shoot the breeze.”

They were attracted to not only classic group harmony records, but also artists like John Coltrane, Albert Ayler, and others who pushed jazz beyond traditional Western harmonics. That improvisational spirit influenced their later musical collaborations, but before the two began playing together Kaye took one last deep dive into the world of rock ‘n’ roll singles. When Kaye was working at Village Oldies, he came to the attention of Elektra Records president Jac Holzman. “Jao called me in one day and asked if I would be an independent talent scout for the label. And he also had an idea for an album called Nuggets, which would compile songs that had kind of fallen between the cracks.”

“Kaye’s article spoke to Smith about her own youth, when boys would gather to harmonize on doo-wop songs in southern New Jersey. She called him up and began dropping by Village Oldies, which sold vintage 45 rpm singles.”

Nuggets was an influential anthology released in 1972 by Elektra-sort of the garage rock equivalent of Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music. A record collector from a young age, Kaye got more serious about his obsession when he drove across the country in 1967 while listening to local radio stations and then seeking out the singles he heard, some of which made their way into Nuggets. The album was like a roadmap for mid-1970s punk bands, who gravitated toward Count Five’s “Psychotic Reaction,” the Standells’ “Dirty Water,” and Nuggets’ 25 other tracks.

The simplicity of those songs—which walked the line between proto-punk angst and playful bubblegum fun—was refreshing at a time when rock had become overly complex. “It was a way to reconnect with the virtues of the short and very catchy single, “Kaye said of the collection’s appeal to the punk bands that played CBGB. “They were just innovative bands that were taking a step backwards to see what made a great record, in the same way that Nuggets looked at that moment in time and showed that these were great records that had certain virtues.”

Kaye’s liner notes for Nuggets—which include an early use of the term “punk rock”—celebrated the kinds of bands that were “young, decidedly unprofessional, seemingly more at home practicing for a teen dance than going out on a national tour.” His friend Greg Shaw championed this kind of music in his self-published magazine Bomp! and he also wrote a rave review of Nuggets in national rock magazine Creem. Under the headline “Psychedelic Punkitude Lives!!” Shaw marveled, “I never thought I would see the day when anybody’d take this music seriously.”

While Kaye was in the thick of compiling Nuggets, he sent a letter to Shaw that captured this critical moment in his life. “At the end of the letter I said, “Oh, I’m doing some cool stuff, but next week I’m going to play at St. Mark’s Church with a local poet, and that should be interesting. This was January 1971, and I have to say at that moment my creative life begins—because in that moment, I’m thinking about Nuggets and I started playing with Patti.”

Smith was interested in doing public poetry readings, though she was wary of many of the poets’ staid, practiced delivery. Around this time, Beat poet Gregory Corso started taking her to readings hosted by the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church, a collective based at the same church where Theatre Genesis was located. It was home to A-listers like Allen Ginsberg, Robert Creeley, and Ted Berrigan, but Corso was less than reverent. He heckled certain poets during their listless performances, yelling, “Shit! Shit! No blood! Get a transfusion!” Sitting at Corso’s side, Smith made a mental note not to be boring if she ever had a chance to read her poems in public.

“The simplicity of those songs—which walked the line between proto-punk angst and playful bubblegum fun—was refreshing at a time when rock had become overly complex.”

On February 10, 1971, Gerard Malanga was scheduled to do a reading at the Poetry Project and he agreed to let Smith open for him. Her collaborations with Shepard taught her to infuse her words with rhythm, and she sought out other ideas about how to disrupt the traditional poetry reading format. “Patti kept herself kind of distant from the rest of us in the plays she was in,” Tony Zanetta recalled. “She wasn’t singing at that point, but she had a very rhythmic performance style as a poet that was very musical, very rock ‘n’ roll.” For the St. Mark’s event, Shepard suggested that Smith add music—which reminded her that Lenny Kaye played guitar. “She wanted to shake it up, poetry-wise, and she did,” said Kaye, who recalled that it was primarily a solo poetry reading, with occasional guitar accompaniment. “I started it with her,” he said. “We did ‘Mack the Knife’, because it was Bertolt Brecht’s birthday, and then I came back for the last three musical pieces.”

Setting chords to her melodic chanting, Kaye recalled that she was easy to follow because of her strong sense of rhythmic movement. “I hesitate to call them ‘songs’,” but in a sense they were the essence of what we would pursue,” he said. “But it wasn’t really meant to be a band. It wasn’t meant to be anything more than just a performance, an artistic moment in time, but as it turns out, that was the moment where everything turned around for me.” The same was true for Smith, whose reading opened up several opportunities—from Creem printing a suite of her poems to the publication of a poetry chapbook for Middle Earth Books. One of the poems she performed that night, “Oath” (which begins, “Christ died for somebody’s sins / But not mine”), was adapted for her 1975 debut album, Horses.

Punk compatriots Richard Hell and Tom Verlaine followed a similar path from poetry to music. Born Richard Meyers and Tom Miller, they met in the mid-1960s at a boarding school in Delaware and were both drawn to New York. They settled into a life of letters and worked at several bookstores, including Cinemabilia, where future Television manager Terry Ork and An American Family‘s Kristian Hoffman worked. Verlaine also hung around the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church, a block from his apartment, and Hell had already been publishing his own poetry magazine, Genesis : Grasp. “I started when I was 17 and I brought out six issues across four years,” Hell said. “It was like a high school literary magazine. I was very ignorant, and I was not a very good writer, and I was just trying to figure out what I was capable of.”

“By the time I did the last issue,” he continued, “I was printing them by myself on a $300 desktop offset printer, like the size of a milk crate. The next stage after Genesis : Grasp was about starting fresh and doing something that would achieve what I was grasping at. That was Dot Books.” Hell started the Dot Books imprint in 1971 with the intention of publishing a list of five books, including Smith’s poetry, but he wound up printing only a collaboration between himself and Verlaine, as well as a book by Andrew Wylie—who became the infamous literary agent known as “the Jackal.” Wylie, in turn, published Smith’s first poetry book, Seventh Heaven, in 1972.

Hell saw Smith perform several times between 1971 and 1973: at her poetry debut at St. Mark’s Church, in the play Island, and even in a performance at the gay disco Le Jardin. “She fulfilled Andrew’s demand for an electrifying, rock-and-roll-level poetry,” Hell recalled. “Patti was triply stunning at the time, not only because her stuff was hair-raising on the page, but because her performances were so seductive and funny and charismatic that the writing was lifted way beyond the page, and then, third, she was self-possessed and plugged in to the point that she would improvise and riff extensions as she read, like a bebop soloist or an action painter, off to a whole other plane beyond the beyond.”

“Corso was less than reverent. He heckled certain poets during their listless performances, yelling, “Shit! Shit! No blood! Get a transfusion!” Sitting at Corso’s side, Smith made a mental note not to be boring if she ever had a chance to read her poems in public.”

Smith had already published Witt, her second book of poetry, when she began working with Hell on her Dot Books poetry volume. During this time, Hell and Verlaine began writing collaborative poems, sharing a typewriter much as Smith and Shepard did with Cowboy Mouth. “Writing the poems was so much fun,” Hell recalled. “Night after night we’d be up late with maybe a quart of beer, or a fresh-scooped pint of vanilla ice cream from Gem Spa, in Tom’s bare rooms, smoking cigarettes and passing the typewriter back and forth.” As their writing experiments progressed, Hell thought it would be fun to conceive of it as a work of a separate third person. Verlaine liked the idea and suggested making the author a woman, Theresa Stern.

“Feminism and androgyny and transvestitism were in the air,” Hell wrote. “We’d cash in! I started imagining her biography: Theresa Stern became a Puerto Rican prostitute-poet who worked the streets of Hoboken, New Jersey. Her debut book, Wanna Go Out? was published in 1973 just as Hell and Verlaine were forming their first band, which evolved into Television “I had a book of Patti’s that we had compiled with me as editor, and there was a book of mine, and a book of Tom’s.” Hell said. “But it was just Andrew’s book and Theresa’s book that were actually published. The other books were ready to go, but then I got into rock ‘n’ roll and I just transferred all my energies to music. And so did Patti.”

Hell and Verlaine cared deeply about writing, but they knew they would have a more pronounced impact through music. One of their key sources of musical inspiration was Lenny Kaye’s Nuggets compilation, which Verlaine brought home one day and listened to constantly. “It was a very small self-contained world downtown and, basically, you could mix and match.” Kaye observed. “There was a lot of interweaving between the literary and the cinematic worlds, and musical performance, and it didn’t seem to have many boundaries.”

__________________________________

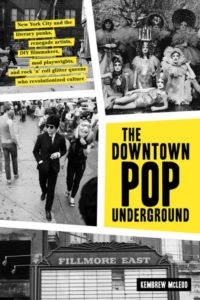

From The Downtown Pop Underground: New York City and the Literary Punks, Renegade Artists, DIY Filmmakers, Mad Playwrights, And Rock ‘n’ Roll Glitter Queens Who Revolutionized Culture. Courtesy of Abrams Books. Copyright © 2018 by Kembrew McLeod.