The Model for America’s Modern Craft Beer Boom? Inside the Small-Brewer Scene in 1950s San Francisco

David Burkhart on Anchor Brewing

As the 1950s wound down, the proliferation of mass-produced, heavily marketed light lagers took an increasing toll on America’s—and San Francisco’s—small brewers. But a number of local establishments still proudly featured Anchor’s signature product, in particular the Crystal Palace Market between Market and Mission at 8th Street. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, it was a “sprawling, pungent, cheap and exotic carnival of delicatessen and delicacy.”

During the 1940s and 50s, Austrian Joseph Erdelatz served Anchor Steam and hot dogs at his bar in the southeast corner of this vast, colorful marketplace. Locals called it the “Steam Beer Parlor,” scarcely imagining its pivotal role in Anchor’s or its beer’s survival. For had it not been for the Crystal Palace, there might never have been an Old Spaghetti Factory, and without the Old Spaghetti Factory and its charismatic owner, Fred Kuh, there might be no Anchor Steam Beer today. Fritz Maytag, who tells the story better than anyone, shared it with me a few years ago:

Ah, Fred. A man of good taste. He had lived in Chicago and been to the Sieben’s Brewery, where I later bought our bottling line. They were the last brewery in America to have a restaurant in the brewery, a little Bier stube. And when he came to San Francisco for a visit, on the way into town from the airport, the very first thing his friend did was take him for a visit to the crystal Palace Market, sort of the equivalent of today’s farmers’ market. He recognized it immediately as similar to the great traditions of good food in Europe. Then his friend took him to the taproom at the crystal Palace Market, where they served Anchor steam on draught. Fred told me that he vowed that day, in the bar, drinking Anchor steam, that he would move to San Francisco, open a restaurant, and serve only Anchor steam Beer on draught.

Photo by Bob Welch

Photo by Bob Welch

Frederick Walter Kuh moved to San Francisco in 1954, where he became a waiter/bartender at the Purple Onion. Two years later, on October 19, 1956, Kuh and fellow “founding father” James B. Silverman opened the Old Spaghetti Factory Café & Excelsior Coffee House at 478 Green Street, in the former home of the Italian-American Paste [sic] Company. The OSF became San Francisco’s “first camp-decor restaurant,” Fred later told the San Francisco Examiner, “but it wasn’t called camp then.” Early on and counterintuitively, he advertised his bohemian North Beach watering hole and its “Steam Beer Underneath a Fig Tree” in the New Yorker. And the first person Kuh acknowledged on the OSF’s offbeat menu, for his “material and spiritual help,” was “Joe Allen of the Anchor Steam Brewery.” Fritz continues:

And Fred Kuh served, on draught, Anchor Steam Beer only, all the years he was open. He had bottled beers, but no other beer on draught ever. And it was a booming place with young people. It was a target for the brewers. Imagine all the salespeople from Budweiser, Coors, and Miller, who would call on Fred at the Old Spaghetti Factory and tell him that he couldn’t possibly survive as a business if he didn’t have their beer on draught. And he told them all to go jump in the lake.

Fred Kuh had made good on his vow.

Fred Kuh at the OSF. Photo by Fritz Maytag

Fred Kuh at the OSF. Photo by Fritz Maytag

Though Kuh’s North Beach eatery was thriving, the Crystal Palace fell victim to changing tastes and times. On April 22, 1959, its landlord announced that the thirty-six-year-old market, with its legendary Steam Beer Parlor in the back, would close August 1 to make room for an $8 million, four-hundred-room “luxury motel.” “Progress,” scoffed one newspaper.

The impending obsolescence of one of his two best accounts got Joe Allen thinking. Business was good, and money, thanks to his sister Agnes’s management, was not a problem. And his brewery—the oldest in the West, the smallest in America, and The Only Steam Beer Brewery in the World—was still selling all the beer he could make, about a hundred half-barrels a week. It was more of a calling than a career, and Joe was Anchor Steam’s unflappable high priest, deeply devoted to the joys of small brewing and the integrity of his product. But he was seventy-one. The robust brewer of the robust beer could no longer hoist kegs with the gusto of his younger days. Clyde and Jene had moved on, and there was no heir apparent. He hoped that someone would come along to take his place, but nobody did. So Joe and Agnes weighed their options and made a decision.

Image via David Burkhardt

Image via David Burkhardt

*

On May 28, 1959, Joe wrote Last in his little brewbook, above the brew number (20) and date. On June 4, he made Brew #21, his last kräusen brew. He racked his last Steam Beer on June 15, his final entry simple but profound, almost like a benediction: Very Good. Anchor’s last day was Saturday, June 28, 1959. “The taps are running dry today on a full-flavored souvenir of San Francisco’s past,” lamented the Chronicle. It was the end of an era. “Many a lover of malt beverage drank his tears with his beer in California last week,” wept the New York Times. “The last surviving Steam brewery dating from the Forty-Niner era of San Francisco [has] closed its doors More than thirty taverns in California have been customers of the Anchor Brewery, which shipped out its final half barrel in late June. Some of these establishments had built their business largely on Steam beer. Their owners, as well as customers, are in mourning.”

Mourning indeed, as if for a brother lost at sea. The Chronicle interviewed the dispirited California commoners. “This has broken our hearts,” grieved Fred Kuh at the Old Spaghetti Factory. Across the Bay in Berkeley, Sam Wilkes Jr.—whose restaurant, The Anchor, got its name from the beer he had served there since 1934—described his customers as “very perturbed.” At the recently opened Old Town Coffee House in Sausalito, owner Courtland Turner Mudge had been serving five hundred glasses of Anchor a day. Distraught regulars clamored for one more taste of Steam, including “one old fellow [who] got away from his nurse and came in for a last glass.” The uproar was understandable. “The people are upset because they know they’re losing an honest product, one that’s 100 per cent malt and one nobody else has made.”

*

Among the tearful at Mudge’s place was Sausalito “ark-dweller” Lawrence Jackson Steese. A smalltown Minnesotan like Joe Allen, Steese was born in Bibawik on April 30, 1912. By 1940, Steese was coopering for a Connecticut distillery. His sundry jobs would include road builder, carpenter, seaman, plumber, handyman, homebrewer, bartender, and Death Valley talc miner. The latter “makes the throat terribly dry,” Steese told the Chronicle, “and beer is the only beverage that makes you feel better.”

But it wasn’t until he arrived in San Francisco in the mid-1950s that the beer lover found Steam. “I liked it and went to see the old man who brewed it. I’ll never forget the feeling that hit me as I entered the place. It was big, silent, and there was a smell of something alive, like when you bake bread. The whole place had the dignity of a cathedral. Where in our society can you find a place of work that has this dignity?” He was smitten.

Seeing the Bay Area’s lugubrious response to the end of Steam, Steese offered to keep the kettle boiling. Although Allen had other suitors, he was impressed by Steese’s sincerity. “I turned down all the Ivy-League briefcase boys,” Joe told Marin County’s Independent Journal (IJ), “because they didn’t look like they would be the type to carry on the old Anchor steam beer tradition.” But he had confidence that Steese would surely do it “as it should be done.” So Allen said yes.

__________________________________

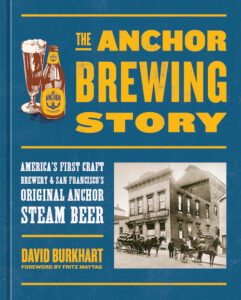

Reprinted with permission from The Anchor Brewing Story: America’s First Craft Brewery & San Francisco’s Original Anchor Steam Beer by David Burkhart, foreword by Fritz Maytag, published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House.