The Mindfuck: Returning to My Mennonite Homeland

Rachel Yoder Goes Looking for... Rachel Yoder?

At the museum, I was eager for history to come to life before my very eyes. I was led through constructed sets that were supposed to make me feel as if I were in places of holiness. I saw stained-glass windows and a red barn wall with hay falling from an open loft. The dungeon contained a pit with a mannequin dressed in rags and a Bible sewn to its hands. Real torture devices loomed everywhere.

I became suspicious of absolute rules governing space and time as I walked through rooms and touched glass boxes containing relics of my abandoned childhood: wooden toys built for godly play, a jar of peaches I’d filled years ago with my small hands. I picked up a telephone and was connected to the singing at my grandmother’s funeral, foreign, with the melody of a moan. I passed the hull of a great ship and then bent beneath its deck, examining the graffitied walls. Martin Kintig, 1693, a pair of crosses, Noah, and vagina were chalked there, evidence that my mounting theories of simultaneity and anachronism would prove true.

Uncle insisted I enter a room in which the floor vibrated with catastrophes and he could summon the wind at will. My teeth buzzed inside my mouth, and my hair blew up around my head. Natural disasters flashed on the wall, and then happy Mennonite women offered injured natives refreshing drinks. Men raised houses from the ground with their bare hands.

Finally, Uncle shut me in the church display to contemplate what I had learned. In the pew, I waited, and then God descended from speakers. Lights flared and dimmed in coordination with His recorded words. The church perfectly built itself so as to evoke in me memories of the first church. But instead all I could think of was my grandmother’s cold face and her body laid out in this very room, or a copy of it, years ago. Beneath the fields of Shipshewana, Amish men grew their long white beards longer and pulled tight wraps of sod against the chill of the dirt. The women kneaded the dirt with their hands. Were I to walk over their graves, they would roll.

I saw myself moving over vast oceans of pure green, the earth churning beneath my feet. Soon, pale fingers sprouted through the dark earth, and before long whole fields grew with hands. I walked for seasons, watching their wrists mature into strong arms. The tops of their white heads formed ghostly islands in the dirt. They grew, and their arms waved like wheat, and I could see their heads strain against the dirt. Soon, faces appeared, and they opened their eyes as if from sleep. The fields at night glowed white with flesh, and their mouths opened and closed to catch the wind. This would be my harvest, I said. This would be my good work. In the morning, I went to the fields and took their hands. I pulled them to their feet. The God voice in the speakers suggested prayer, but instead I wandered among the dead of the land. I felt they had answers, but they would not speak.

After my moment of silence in the fake church, I informed Uncle of the evidence I’d uncovered regarding convergence and simultaneity and how one might go about approaching unity, but he accused me of being the one to pen vagina on the ship’s wall. He was convinced I would fabricate data regarding how the present changes the past and how unholy and holy commiserate. I protested, but he was already gone to instruct the ship wall be washed clean of all suspicious markings.

I perused the gift shop one last time until I found the large ruby jewel of raspberry jam glistening in its jar, which I purchased with regards. I also considered the book Plain and Amish: An Alternative to Modern Pessimism, but felt my pessimism was, to large and small extents, what propelled me, and I did not want to jeopardize what little bit of motivation I still had left.

![]()

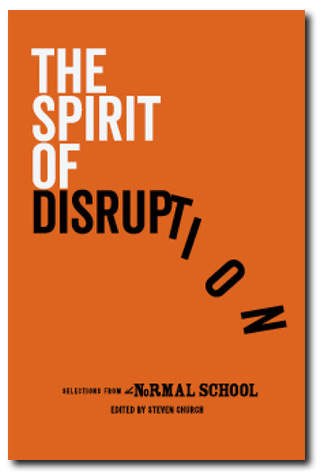

From The Spirit of Disruption: Landmark Essays from The Normal School, edited by Steven Church (Outpost19, 2018).

Rachel Yoder

Rachel Yoder is a founding editor of draft: the journal of process, which features first and final drafts of stories, poems, and essays, along with author interviews about the creative process. She is also the creator and host of The Fail Safe, an interview podcast that explores how today’s most successful writers grapple with and learn from creative failure. Her short stories and essays have recently appeared in The Southern Review, StoryQuarterly, Catapult, and Gulf Coast and her work has also been awarded The Editors’ Prize in Fiction by The Missouri Review and with notable distinctions in Best American Short Stories and Best American Nonrequired Reading. She is currently a 2017 Iowa Arts Council Fellow and lives in Iowa City. racheljyoder.com