The Mild Mannered Englishman Who Was the World’s Most Prolific Ghost Hunter

Ben Machell on Paranormal Investigator Tony Cornell

A middle-aged couple park their car outside a modest suburban house. The husband turns off the engine then returns his hands to the wheel, eyes forward and jaw set. His wife looks out of the passenger window, her expression both faraway and eager. They sit in silence for a moment. Then, from the front steps of the house, a grandmotherly figure appears and beckons them. The wife raises her own hand in tentative reply. Without a word, she opens the passenger door and makes her way down the drive. The husband watches her go. He shuts his eyes and inhales deeply. He unbuckles himself and follows.

The old woman ushers them warmly into her home, leading them through a chintzy hallway toward a living room door. She stops outside and turns to them. “He’s been waiting for you,” she says, smiling. “Come.”

Suddenly, the quiet is broken by a voice, high-pitched and smiling.

She pushes open the door and guides them into a darkened room. Heavy curtains are drawn, and a single red light bulb glows from the ceiling. Half a dozen other figures are already sitting in chairs formed in a semicircle, but they say nothing as the husband and wife join them. The old woman stands facing the room, her face cast in shadow and red light. She surveys the people present and smiles. She shuts her eyes and raises her upturned palms, and the guests do the same, gently taking the hands of their neighbors. A small cymbal begin to chime in a gentle, steady rhythm. The red light begins to flicker and dance.

The husband and wife sit side by side, hand in hand, their eyes shut. The old woman is speaking, but her voice is far away and indistinct. A heavy sense of drowsy dislocation slowly overcomes them. The old woman’s voice stops, and there is nothing but silence. It passes for five seconds, ten seconds, fifteen. Suddenly, the quiet is broken by a voice, high-pitched and smiling.

“Mummy?”

The husband and wife both open their eyes. The man draws a sharp, startled breath. The woman can only make a small sound. She puts a hand to her lips then reaches forward, before drawing her hand back. In the center of the room, swathed in shadow, is the faint spectral outline of a small boy.

“Mummy, Daddy, it’s me,” the shape speaks brightly. “I’ve missed you so much . . .”

Later, the husband and wife say goodbye to the old woman on her front doorstep. The wife embraces her. They walk back to their car and take their seats. They hold hands as they both begin to weep, smiling at one another as they convulse with grief and joy.

In the lounge of a small terraced house, a family eats fish and chips in front of the TV. Two boys sit on the floor, and the mother and father are in old armchairs. It is dark outside, and the room is quiet and cozy.

Suddenly, the father’s eyes flick toward a dark corner of the room. They widen with alarm and he sits forward in his chair. “Oh God, no,” he mutters, getting to his feet but backing away in a low, guarded crouch. “God, please, no! It’s him!” he shouts. His family all turn to look at him and then at the corner of the room. But they see nothing.

His wife springs to her feet. “Get out of the house quickly,” she urges. “Run!” Her husband makes to flee, but as he moves toward the door he cries and stumbles, then falls to the floor. “He’s on me!” he screams, writhing and wrestling with some unseen assailant. “Help me! His claws . . . the Black Dog . . . he’s tearing me!” The wife ushers the two frightened boys behind her, and watches on helplessly as her husband screams in agony and terror, thrashing his arms and legs.

After a minute of this, the man’s cries die out, as do his movements. Soon, he is a panting, shaking heap on the floor. His wife kneels down beside him to tend to him, but he brushes her hand aside. “Stay away,” he mutters. But she persists. She points to his shirt, which is now soaked through with blood in different patches up and down his chest and stomach. Exhausted, he allows her to unbutton it. And as she does, she reveals an entire torso covered in old scars and fresh, deep, bloody cuts.

A thirteen-year-old girl watches on impassively while her mother and father lavish praise upon a painting her younger brother has produced. He sits at the kitchen table proudly while his parents coo and stroke his shoulders with pride. The mother glances up and sees her daughter watching, and her expression becomes altogether less indulgent. “Shouldn’t you be starting your homework?” she asks crisply.

The girl purses her lips but turns on her heels and leaves the room. The sound of her stomping up the staircase causes her parents to share a look of weary consternation. The little brother is still contentedly working on his painting, dipping his brush into his pots and then smearing it across the paper.

Then, suddenly, he frowns.

“Hey!” he shouts, as a large drop of water lands on his artwork, spoiling it and making the paint run. Another drop falls. He and his parents all look up at the ceiling, where a sudden leak, directly above them, is beginning to build a drip-drip-drip momentum. The father runs his hands over his head in despair. The mother shouts her daughter’s name. “Jenny!” she barks, before racing up the stairs. “Jenny, where are you?”

As she reaches the second floor of the house, she sees that the carpet is drenched. Water is running down the walls and dripping through light fixtures, as though the house itself is sweating out a fever. She squelches along a landing, calling her daughter’s name again, only stopping to peer into the family bathroom, although no taps are running which could account for the deluge. “Jenny!” she calls again, furious now.

I look at the various papers being tenderly examined and wonder, prior to today, how long they had been sitting untouched, cataloged and filed away out of sight and mind.

She catches a faint reply—“What?!”—and marches toward its source. She flings open a bedroom door, and her daughter is sitting at a desk, her schoolbooks open and a pen in her hand. The room is dry and still. The girl looks at her mother glowering in the doorway. Then she looks down at her sodden feet. She rises from her desk and fixes her mother with a defiant stare, fists bunched by her side. “I’ve told you. It’s not me.”

It is a drizzly afternoon in the spring of 2023, and I’m in the Special Collections room of the Cambridge University Library, waiting at the front desk a little nervously. It is my first time here and, hidden away on the top floor of the vast building, there is a peculiar sense of having entered a place where time does not quite pass as it should. I glance around. A man sitting at one of the heavy wooden tables is wearing a pair of latex gloves, and carefully turns the pages of a manuscript that could be five, six, seven hundred years old. Two students have unrolled what looks like an incomplete treasure map, and lean over it with magnifying glasses, murmuring to one another. An elderly woman sits beside a small pile of old leather-bound books and rubs her eyes wearily.

All of these items are unique—mementos of lives and events long past—and are kept in the library archive until somebody requests to see them. I look at the various papers being tenderly examined and wonder, prior to today, how long they had been sitting untouched, cataloged and filed away out of sight and mind. Years? Decades? Generations? These thoughts are interrupted by the soft voice of a librarian, who has arrived at the front desk with a trolley, on top of which are stacked several cardboard boxes. Some of them bear the words “CORNELL,” written in black marker pen. She hands me a slip to sign, and then I carefully lift the first box off the trolley, feeling oddly self-conscious. The librarian smiles. “There’s an awful lot more in the archive,” she says, as I turn to find a table.

I take a seat and look inside the box. I don’t know what I am expecting to find or where I should begin. I pull out, at random, a typed report of some two dozen pages titled “Is Emotion the Psychic Trigger?” I place it on the table beside me and reach into the box again. This time, I produce a faded foolscap folder with “Telepathy, Apparitions and Precognition” written on it. I keep going. There are several spiral-bound shorthand notepads.

One has the words “Spontaneous Cases” written on the cover in ballpoint ink, accompanied by time stamps. Sheerness, 1987. Southampton, 1990. Thetford, 1991. I begin to skim the contents, doing my best to read the quick, slanting handwriting inside. Several pages describe a visit to the home of a trawlerman who is repeatedly attacked by a hideous black dog only he can see. This beast, nonetheless, has left many bloody lacerations on the man’s body—including “five deep cuts on the underside of upper left leg,” according to the notes—and the intervention of a local vicar has had no apparent effect.

I keep reading. Hours slide past without my noticing. I only move in order to return to the front desk for another box. There are newspaper clippings, from the 1950s through to the 2000s, concerning ghost sightings, or reports of poltergeists in market towns or children who appear to possess uncanny extrasensory powers. There is a rotting photo album containing pages and pages of eerie, Edwardian-era “spirit photographs”: disembodied faces floating in faded sepia. There are strange cards marked with odd monochrome symbols.

In one folder, I find a series of letters from the 1960s with Soviet stamps and postmarks, which have been sent from a professor at Leningrad University. These letters talk excitedly of cooperation between Russian and British researchers into psychic phenomena, despite finding themselves on opposing sides of a Cold War. Another letter, dated February 1960, is from the Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung, who writes of his lifelong interest in the paranormal, and who provides dozens of densely worded paragraphs on the subject. “In the case of telepathy, we might be able to establish a causal explanation,” writes Jung. “But in the case of precognition, such a chance does not exist.”

Most of the letters in these boxes, however, do not come from Soviet psychic researchers, or famous thinkers like Jung. Rather, I find they have been written by ordinary people. One letter, brisk and to the point, is from the neighbor of a family in Lancashire, who find that for reasons that cannot be explained, their home is regularly left sodden by water which seems to materialize from nowhere. “Every night for the past three weeks, usually between the hours of 4 p.m. and midnight, considerable quantities of water pour from out of the air in every room of the house,” the neighbor writes. “The local water board have been and ruled out the possibility of a mains leak, and the ‘experts’ have been and cannot offer any help or even an explanation . . . If you cannot come and see this, please write any suggestions. You must know how these things are tackled.”

What do you do when you are caught up in events that cannot be explained?

I keep sifting. I read a handwritten note in which a man describes how his honeymoon in an old country inn was repeatedly interrupted by the appearance of a spectral figure, which both he and his wife saw. “About 5:30 a.m. I awoke suddenly and saw a pretty young girl around 13 to 15 years of age standing near the settee in our room,” he writes. “She had blonde hair and looked as if she were in a nightdress. Her face was pale and she had some sort of garland around her head. She was not transparent but solid, and had a look of sadness on her face.”

In another letter, dating from 1963, a man complains that he is visited nightly by the ghost of a woman who subjects him to “interference, such as fondlings and pressure against my body,” which has deprived him of sleep for weeks. “My impression, Sir, is that this is some woman who has probably liked men and decided to have a go at me, even though she is no longer living in the flesh.”

What do you do when you are caught up in events that cannot be explained? When your understanding of reality is challenged in such profound and disturbing ways that the sureties of science, religion or simple common sense provide neither comfort nor closure? For decades, thousands of ordinary people who found themselves in these circumstances called upon the help of a balding, bespectacled man from Cambridge. His name was Tony Cornell, and between the 1950s and his death in 2010, he was one of the most prolific parapsychologists—which is to say, one who investigates psychic phenomena and other paranormal claims— on the planet. The contents of these cardboard boxes, stored deep within the Special Collections archive, once belonged to him.

And underpinning everything—the papers, notes, cuttings, photographs, correspondences and transcripts—is one question, asked again and again and again. What happens when we die? When our bodies fail and our hearts stop and the lights go out, is that it? Are we all faced with an eternity of nothingness, of blank, perennial non-existence? Or is there more to humankind than our physical bodies? Do we possess a soul, spirit or sense of consciousness that can transcend physical mortality? The contents of these boxes are the memories of a man who spent his life probing the very edges of reality. Testing the barrier between life and death.

I had first encountered the name Tony Cornell—and found myself drawn into the world of psychical research—some six months earlier. It began with a visit to my grandmother’s house. She was ill—she was dying—and, because she was a practical-minded woman, she began pointing out the items around her house I could have when she was gone. Among these was a leather-bound box, inside of which was a crystal ball.

I had known about the crystal ball since I was a young child and had always been fascinated by it. Sometimes, my grandmother would bring it out of the box and let me hold it, smooth, cold and heavy in my hand, and she would explain that it had belonged to an aunt who believed she possessed a supernatural gift of foresight. This aunt would look into the ball and see the face of some distant relative, and then announce that the family would be having an unexpected visitor, before dispatching someone to the butcher’s to buy the very best pork chops for the occasion. Everyone would sit at the dinner table expectantly, their pork chops in front of them, waiting for a knock at the door that would, inevitably, never come. It is possible, my grandmother conceded, that this particular aunt just really liked pork chops.

When I returned home, I thought a lot about the crystal ball that would very soon be mine. Perhaps to distract myself from the sadness I was feeling at my grandmother’s failing health, and perhaps because death and what may lie after was on my mind, I began to read up on mediums—people who claim the ability to do everything from predicting the future to communing with the spirits of the dead—and quickly fell down a rabbit hole of online research. It was during these long nights hunched over my laptop, reading about ectoplasm and disembodied voices, that I came across a reference to a man who had visited dozens of séances and investigated other potentially supernatural events that were of the uninvited and unplanned variety.

Cornell’s role as an investigator of so-called “spontaneous cases” saw him returning time and again to the unsettling spaces that exist just on the periphery of our ordered, tidy and rational lives, and which we all do our best to ignore: ghosts.

Cornell would arrive at the scene of these disturbances in a suit and tie, carrying a bag containing notepads, tape recorders, cameras and, on occasion, other, homemade instruments. Personable, matter-of-fact and meticulous, in both appearance and manner he could easily have passed for an insurance claims assessor or senior police detective rather than a ghost hunter, albeit a senior police detective who was also a skilled hypnotist and who would not balk at creating a makeshift Ouija board in order to attempt communion with the dead.

A member of the UK’s Society for Psychical Research (SPR), an institution founded in 1882, Cornell’s role as an investigator of so-called “spontaneous cases” saw him returning time and again to the unsettling spaces that exist just on the periphery of our ordered, tidy and rational lives, and which we all do our best to ignore: ghosts. Spirits. Premonitions. Psychic powers. Glimpses of other worlds that throw into question everything we take for granted about life, death and material existence itself.

At one point, during the 1980s, Cornell was invited to spend a week investigating the historic cruise liner the RMS Queen Mary, which was permanently moored in Long Beach, California, and known for its many reported hauntings. Working with American colleagues—including a group of six mediums who had all been flown in from Atlanta for the occasion—he surveilled the huge vessel, looking for signs of the ghosts who had made the old Cunard liner their home: the “Woman in White” who could be seen dancing alone in the shadows of the first-class drawing room, the unquiet spirit of a ship’s chef who had been murdered on board as well as that of a young seaman who had been crushed to death in the bowels of the ship and whose cries could still be heard by staff at night.

When a family living in a remote rural home reported that a malign power seemed to have taken over their house, Cornell was dispatched. He arrived to find a terrified mother, father and son in a bungalow where light fixtures would swing back and forth unaccountably then burst without warning, where small fires broke out suddenly but persistently, and where tight plumbing screws seemed to undo themselves, causing pipes to loosen and floods to occur. Houseplants would wither and die. Pets fared no better. “A hamster and several birds died within two days of being housed in the bungalow,” the notes on the case report. “Five puppies had died within two weeks of being brought there. All had expired in the morning with a yelp, as if they had been shot.”

On another occasion, he went to meet the Lancashire family who had reported that water continually appeared from no apparent source, soaking their possessions and, on some occasions, flying through the air. A plumber had already stripped the house bare and ruled out any possibility that the water was coming from their pipes or any other traceable source. Over the course of a weekend with the family, interviewing them and observing their lives, Cornell concluded that the thirteen-year-old daughter was somehow at the center of these events.

While she admitted that she sometimes felt jealous of the attention her parents lavished upon her younger brother, she denied that she had anything to do with the strange appearance of water, which often forced her and her family to sleep on camp beds in the living room. Cornell believed her.

She also admitted that, sometimes, she and a friend played with a Ouija board. Before he left, he carried out a psychokinesis (PK) test on the girl, and asked her to throw a pair of dice thirteen times and aim to get as high a score as possible. Then he asked her to throw a pair of dice thirteen times and aim for as low a score as possible. She was able to throw considerably higher scores when she was aiming to—the results only have a seventy-five to one chance of happening naturally.

Week after week, month after month, year after year, Cornell and his SPR colleagues sought out these events—these crises unfolding in ordinary homes in ordinary towns to ordinary people—and attempted to deduce what, exactly, was happening: a calm, steady, scrutinizing presence amid the chaos and fear. Because although he possessed a deep curiosity about the supernatural, he was also a natural skeptic.

When attending séances, he produced precise sketches of seating positions, and on more than one occasion exposed a would-be medium as a fraud. He produced transcripts of the conversations he held with hypnotized subjects, and amassed crates of cassette tapes containing interviews and telephone conversations with the people he encountered.

Reading these questions is like hearing the steady voice of a rational man methodically tapping the wall between reality and something else.

Among his papers, I discover, are copies of the incredibly detailed questionnaires he would ask everybody involved in a case to complete, which allowed him to construct a psychological profile of each individual he encountered and as clear a picture as possible of the frightening or inexplicable events they reported:

“What is your religious background?”

“What kind of books or articles have you read about psychic phenomena or the occult?”

“Have there been instances where one or more people have seen an apparition or ghost? If yes, please describe what was seen.”

“Would you say that the apparition seems to be one that is conscious or aware of its surroundings, that it is an intelligent ‘entity’?”

“Are you taking any medication or non-prescription drugs? If so, what are they?”

“What is known about the building and its previous owners? Is anything known of the location it stands on?”

“Are the events seen to occur more in one spot (or in more than one place) than in others? Where are these places?”

“If you were to pretend this were all happening in a dream, what would you make of it?”

“Have you ever had a ‘run of luck’?”

“Have you ever had, while awake, the vivid sensation of seeing, hearing, ‘sensing,’ or being touched by someone or something which you could not explain by normal means?”

And on. And on. And on. Reading these questions is like hearing the steady voice of a rational man methodically tapping the wall between reality and something else. As evening falls, I return the cardboard boxes to the front desk, leave the library and make my way back to Cambridge station, feeling both exhausted and exhilarated. For a while I come close to falling asleep on the train home, but my mind turns with thoughts of secret Cold War experiments into telepathy, of images of ghostly, garland-wearing girls and terrified trawler-men covered in bloody gashes. The complacent faces of phony mediums swirl in my head, along with unsettling spirit photographs and images of puppies that had died with a sudden yelp for no apparent reason.

Eventually, I fall asleep, lulled by the sound of the train and of a teenage girl rolling dice again and again and again.

__________________________________

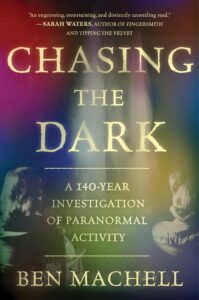

Excerpted from Chasing the Dark: A 140-Year Investigation of Paranormal Activity. Copyright © 2025 Ben Machell. Published by Grand Central Publishing, a Hachette Book Group company. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Ben Machell

Ben Machell has worked for the Times in London since 2005, and is a principal feature writer, interviewer, and columnist for the award-winning Times Magazine. His debut book, The Unusual Suspect, was widely acclaimed and shortlisted for the Golden Dagger at the 2022 Crime Writers’ Association Awards.