David Baptiste’s dreads are grey and his body wizened to twigs of hard black coral, but there are still a few people around St. Constance who remember him as a young man and his part in the events of 1976, when those white men from Florida came to fish for marlin and instead pulled a mermaid out of the sea. It happened in April, after the leatherbacks had started to migrate. Some said she arrived with them. Others said they’d seen her before, those who’d fished far out. But most people agreed that she would never have been caught at all if the two of them hadn’t been carrying on some kind of flirty-flirty behaviour.

*

Black Conch waters nice first thing in the morning. David Baptiste often went out as early as possible, trying to beat the other fishermen to a good catch of king fish or red snapper. He would head to the jagged rocks one mile or so off Murder Bay, taking with him his usual accoutrements to keep him company while he put his lines out—a stick of the finest local ganja and his guitar, which he didn’t play too well, an old beat-up thing his cousin, Nicer Country, had given him. He would drop anchor near those rocks, lash the rudder, light his spliff and strum to himself while the white, neon disc of the sun appeared on the horizon, pushing itself up, rising slow slow, omnipotent into the silver-blue sky.

David was strumming his guitar and singing to himself when she first raised her barnacled, seaweed-clotted head from the flat, grey sea, its stark hues of turquoise not yet stirred. Plain so, the mermaid popped up and watched him for some time before he glanced around and caught sight of her.

“Holy Mother of Holy God on earth,” he exclaimed. She ducked back under the sea. Quick quick, he put down his guitar and peered hard. It wasn’t full daylight yet. He rubbed his eyes, as if to make them see better.

“Ayyy,” he called across the water. “Dou dou. Come. Mami wata! Come. Come, nuh.”

He put one hand on his heart because it was leaping around inside his chest. His stomach trembled with desire and fear and wonder because he knew what he’d seen. A woman. Right there, in the water. A red-skinned woman, not black, not African. Not yellow, not a Chinee woman, or a woman with golden hair from Amsterdam. Not a blue woman, either, blue like a damn fish. Red. She was a red woman, like an Amerindian. Or anyway, her top half was red. He had seen her shoulders, her head, her breasts, and her long black hair like ropes, all sea mossy and jook up with anemone and conch shell. A merwoman. He stared at the spot of her appearance for some time. He took a good look at his spliff; was it something real strong he smoke that morning? He shook himself and gazed hard at the sea, waiting for her to pop back up.

“Come back,” he shouted into the deep greyness. The mermaid had held her head up high above the waves, and he’d seen a certain expression on her face, like she’d been studying him.

He waited.

But nothing happened. Not that day. He sat down in his pirogue and, for some reason, tears fell for his mother, just like that. For Lavinia Baptiste, his good mother, the bread baker of the village, dead not two years. Later, when he racked his brain, he thought of all those stories he’d heard since childhood, tales of half-and-half sea creatures, except those stories were of mermen. Black Conch legend told of mermen who lived deep in the sea and came onto land now and then to mate with river maidens—old-time stories, from the colonial era. The older fishermen liked to talk in Ce-Ce’s parlour on the foreshore, sometimes late into the night, after many rums and too much marijuana. The mermen of Black Conch were just that: stories.

It was April, time of the leatherback migration south to Black Conch waters, time of dry season, of pouis trees exploding in the hills, yellow and pink, like bombs of sulphur, the time when the whoreish flamboyant begins to bloom. From that moment, when that red-skinned woman rose and disappeared as if to tease him, David ached to see her again. He felt a bittersweet melancholy, a soft caress to his spirit. Nothing to do with what he’d been smoking. That day, a part of him lit up, a part he’d no idea was there to light. He had felt a sharp stabbing sensation, right there in the flat part between his ribs, in his solar plexus.

“Come back, nuh,” he said, soft soft and gentlemanlike after his mother-tears had dried and his face was tight with the salt. Something had happened. She had risen from the waves, chosen him, a humble fisherman.

“Come, nuh, dou dou,” he pleaded, this time softer still, as if to lure her. But the water had settled back flat.

*

Next morning, David went to the exact same spot by those jagged rocks off Murder Bay and waited for several hours and saw nothing. He smoked nothing. Day after, the same thing. Four days he went out to those rocks in his pirogue. He cut the engine, threw out the anchor, and waited. He told no one what he had seen. He avoided Ce-Ce’s parlour, the property of his kind-hearted, bigmouth aunt. He avoided his cousins, his pardners in St. Constance. He went home to his small house on the hill, the house he’d built himself, surrounded by banana trees, where he lived with Harvey, his pot hound. He felt on edge. He went to bed early so as to rise early. He needed to see the mermaid again, to be sure that his eyes had seen correctly. He needed to cool what had become an inflammation in his heart, to pacify the buzz that had started up in his nervous system. He had never had this type of feeling, certainly not for no mortal woman.

Then, day five, around six o’clock, he was strumming his guitar, humming a hymn, when the mermaid showed herself again. This time she splashed the water with one hand and made a sound like a bird squeak. When he looked up he didn’t frighten so bad, even though his belly clenched tight and every fibre in his body froze. He stayed still and watched her good. She was floating port side of his boat, cool cool, like a regular woman on a raft, except there was no raft. The mermaid, with long black hair and big, shining eyes, was taking a long suspicious look at him. She cocked her head, and it was only then David realised she was watching his guitar. Slow slow, so as not to make her disappear again, he picked it up and began to strum and hum a tune, quietly. She stayed there, floating, watching him, stroking the water, slowly, with her arms and her massive tail.

The music brought her to him, not the engine sound, though she knew that too. It was the magic that music makes, the song that lives within every creature on earth, including mermaids. She hadn’t heard music for a long time, maybe a thousand years, and she was irresistibly drawn up to the surface, real slow and real interested.

That morning David played her soft hymns he’d learnt as a boy, praising God. He sang holy songs for her, songs which brought tears to his eyes, and there they stayed, on this second meeting, a small patch of sea apart, watching each other—a young, wet-eyed Black Conch fisherman with an old guitar, and a mermaid who’d arrived on the currents from Cuban waters, where once they talked of her by the name of Aycayia.

__________________________________

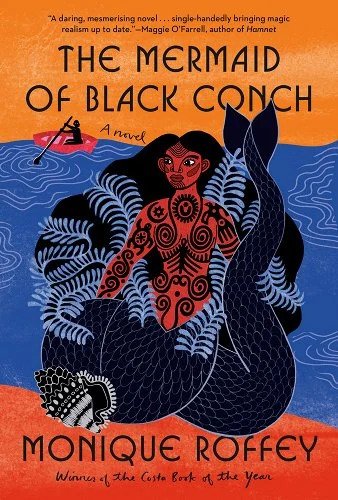

From The Mermaid of Black Conch by Monique Roffey. Used with permission of the publisher, Knopf Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Monique Roffey.