The Mermaid, C'est Moi: Rewriting the Story of a Universal Myth

Monique Roffey on Creating a Feminist Version of a Male Fantasy

It was just after carnival, 2013, when a mermaid came to me. The annual fishing competition was taking place. I watched the boats go out and come back in, daily; saw the large fish (barracuda, tarpon, shark) being hung and weighed; noticed the gallows-type structure at the end of the long jetty, found it ominous. It gave me ideas of death as performance art; the structure had echoes of lynching, too. The famous photo of Hemingway and his family gathered, smiling, proud, in front of five or six massive dead marlin, each of them as big as a cow, maybe bigger; as big as sides of humans easily. The unconscious free associates so smoothly, and quickly. Images breed. Ideas, too.

The gallows gave me ideas about a time when killing fish this huge and glorious was considered heroic and masculine. Like all blood sports, big game fishing is an unfair fight, when the prey is vastly outmatched. While big game fishing is considered a skill (the strike, the fight, landing the fish), heroic it is not.

Strange weather too, that week in Charlotteville. Choppy seas and low grey clouds. A tourist couple had been reported lost in a kayak far off some rocks. Then, news came that a young man had hung himself in the village, a romantic relationship gone wrong, I was already working on a novel that week. But one night, while staying there, my dreams threw up an image of a mermaid hanging upside down from her tail, from those same dreadful gallows, gagged and bound, her deadly hair writhing all over the jetty. She too had been caught during the fishing competition. I reported the dream to a close friend when I returned to Trinidad; she still remembers this. From then on, I doodled and drew the image in my notebooks.

While she’s a hallucination of all humanity, she’s always been written by men. She is the product of the male gaze.

Years later, the mermaid dream had swum around a lot in my “back brain,” and I began to write the words, paragraphs and then chapters of what eventually became The Mermaid of Black Conch. Novels are strange things. They have their own energy and intentions. Within a year I had most of the novel which is now in print. But nobody in the mainstream publishing world in the UK wanted my mermaid book. She, my mermaid, is an experimental work, to be fair; told by three narrators, one a mermaid, and this voice written in verse. My novel is also written in Creole English, Trinidadian parlance, without apology or an appendix of words in the back.

My mermaid is indigenous to the Caribbean, too, dredged from antiquity, not necessarily beauteous; she is messy, dred-locked and covered in tattoos. She shits in a bucket, at first. She is silent, too, mostly. So, I accept she may have been hard to sell. But, after the novel was published by the indie press Peepal Tree Press and won the Costa Book of the Year prize, publishers paid attention. Today, as I write, the novel has now sold in thirteen countries around the world and counting, even in Japan. (I relish the idea of Trinidadian parlance translated into Japanese).

Mermaids, as I have found out since the dream, since my writing and since publication, snag on the unconscious of many. They are a pan global archetypal image. Water is often gendered feminine (La mere), and water is associated with the feminine principal. Women and the ocean have been cross bred by the collective imagination of humanity since antiquity and voila—we have created for ourselves the mermaid archetype. She collectively manifested millennia ago, long before Christ and the Buddha.

She first appears in stories around 3,000 years ago, In Assyria, with the story of Atagaris (more later). Eerily, wondrously, the mermaid is everywhere, in every ocean and many rivers. Every sea and many cultures have mermaid stories and myths. A half and half creature, she is one thing always: an outsider. Often cursed, and often a young woman with a fine singing voice. While she’s a hallucination of all humanity, she’s always been written by men. She is the product of the male gaze. This explains why she is always young and half naked. Middle aged mermaids do not exist, nor do elderly ones. We never see a mermaid with a dress or cardigan on. She is always young, naked, and tragic. She either lures and tempts men, or is herself trapped, having been lured. There are few ancient comic mermaid tales, if any. She is an entrapped creature who sometimes traps others.

While Benin’s Mami Wata will bestow great visionary gifts on those she entraps and allows back to the surface, some mermaids, the sirens in The Odyssey, for example, are to be avoided at all costs; they will lure men to their deaths. Beware: young, sexy, half naked women are dangerous. Mermaids, in my mind, needed an 21st-century update, a feminist rewrite. For starters, they need sexually liberating from their tail, the one that seals up their sex.

In the Caribbean, we have several well-known mermaid myths and legends, the Taino myth of Aycayia is just one of them. Mermaids appear in much fine and contemporary Caribbean art too, my favorite being the work of artist Canute Caliste from Carriacou. Caliste, who died in 2015, had a vision of a mermaid when he was nine years old and he began painting soon after, often mermaids. A fisherman, sea cook and violin player, his paintings, while naïve, have been collected by serious art collectors globally, including The Queen.

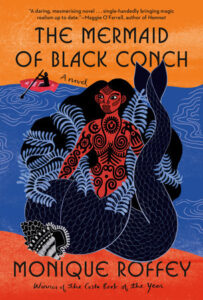

Haitian artist Mireile Delice also had visions of her future and makes vodou flags known as ‘drapos’ made from bead and needlework. She also makes mermaids and I love her image of two mermaids and a comb. In researching my mermaid novel, I also came across an image drawn by Tony Di Terlizzi in Field Guide to the Fantastical World Around You by Arthur Spiderwick. It gave me ideas about my mermaid having a big spikey dorsal on her back. In 2018, I asked my then lodger, artist Harriet Shilito, to draw me a mermaid image for the Peepal Tree Press cover of my novel. I gave her some ideas of how I envisioned Aycayia in my book (a mammoth tail, a non-passive nude) and she came back with the image on the cover of the first edition today.

In the process of researching, writing, and publishing the book I have also become a mermaidologist. I have collected myths and stories from around the world. My favorite story is our first mermaid story—of Atagaris from Assyria. She, legend tells, killed her shepherd lover during sex and the tragedy of losing him made her jump into a lake, trying to drown herself. The Gods came to her rescue and turned her into a mermaid instead. I’ve always wondered how she managed to kill her lover, though. A kinky game gone wrong, a heart attack? Did she squash him to death? There are no details; yet another mermaid story ready to be rewritten!

I’ve come to realize one thing is true: the mermaid, c’est moi. I am bi-national, bi-cultural, of variegated origins. My hair is frizzy, my skin red, my accent code switches according to where I am. British in the UK, Tringlish in Trinidad. Always trust your unconscious and write from the inside out. That’s like a rule. Aycayia, to me, is no stranger and neither are stories of mermaids. They represent the loner woman, the outsider, a half-and-half who travels solo and who now and then reveals herself, pops her head above the waves. She is a chimera, a complex character, a trickster, too, who you shouldn’t fuck with. She’s not just me, but something of her is in all women. She is fecund and alluring and yet trapped and cursed by the patriarchy. She is desirable and yet unavailable. And yes, during lovemaking, she may kill lovers off – simply with the power of her orgasm.

Our mermaid stories won’t die or disappear. They’ve been imagined and planted in our psyche long before we invented a male and omnipotent God. We will keep thinking about mermaids, I’m sure, for centuries in the future. We need them more than ever now, as our planet comes so drastically out of balance. Mermaids are a pagan fusion, from a time when we were closer to nature. They are a conjuring of two very powerful archetypes: ocean and woman. Both represent Gaia, Mother Earth, the Mighty Feminine.

__________________________________________________________

Monique Roffey’s The Mermaid of Black Conch is available now via Knopf.

Monique Roffey

Monique Roffey is a senior lecturer in creative writing at the Manchester Writing School at Manchester Metropolitan University. She is the author of seven books, four of which are set in Trinidad and the Caribbean region. The Mermaid of Black Conch won the 2020 Costa Book of the Year Award and was short-listed for several other major prizes. Roffey’s work has appeared in The New York Review of Books, Wasafiri, and The Independent. She was born in Port of Spain, Trinidad, and educated in the United Kingdom. Her website is moniqueroffey.com.