The Maternal, Feminist Utopias of Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Famous for "The Yellow Wallpaper," Gilman Had an Optimistic Streak

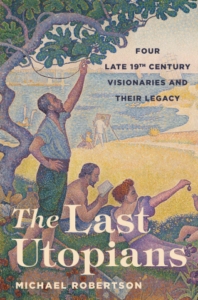

Charlotte Perkins Gilman is best known today for “The Yellow Wallpaper,” a widely anthologized and frequently taught short story that mixes gothic conventions with feminist insights—a chilling dissection of patriarchy that seems as if it could have been coauthored by Edgar Allan Poe and Gloria Steinem. Yet when the story was published in 1892, no one—including Gilman herself—thought of her as a fiction writer. Her contemporaries knew her as a speaker and writer on behalf of Nationalism, the political movement inspired by Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888). Bellamy may have conceived his utopia as a thought experiment, but Nationalists regarded it as a feasible political blueprint. They chose the name of their movement not as an expression of American exceptionalism but as a tribute to the national scale of Bellamy’s economic model, in which the state served as the sole producer of goods and employer of labor.

Nationalists were, for the most part, middle-class socialists who were dismayed by both the plutocratic excesses of Gilded Age America and the violence that attended many of the working-class strikes and demonstrations of the period. They were drawn to Looking Backward’s vision of a near-future America of absolute equality, a utopia achieved through a peaceful process of quasi-religious individual conversion.

Many were also drawn to Nationalism by Bellamy’s stance on women’s economic independence; in the society depicted in Looking Backward, every woman and man earns an equal salary. A substantial proportion of Nationalists were women, and a surprisingly large number of women played leading roles in the movement. Gilman, for example, was Nationalism’s unofficial poet laureate, publishing numerous poems in support of the cause—bouncy light verse that poked fun at conservatives and made an egalitarian future seem tantalizingly possible. Her first lecture to a Nationalist club, “Human Nature,” was characteristic of her distinctive approach. Gilman lauded Nationalism’s challenge to laissez-faire capitalism, saying that it had “struck at a great taproot in striking at our business system, the root of the struggle between man and man.” However, she added, there was another root as deep, or possibly deeper: “the struggle between man and woman.”

Edward Bellamy was certain that, once his version of socialism was established, gender equality would follow. Gilman took a different approach. She believed that women’s independence was a precondition of socialism and that the realization of utopia depended on women’s distinctive contributions. Gilman’s immediate goal throughout her career was to end both women’s economic dependence on men and the middle-class ideal of domestic femininity, in which the obedient daughter left the protection of her father only to assume a supporting role to her breadwinning husband. Other women’s rights activists shared this goal, but for the most part they lobbied for women’s freedom to compete alongside men in the capitalist marketplace. Gilman argued instead that once women were liberated from compulsory domesticity, they would be free to bring their unique perspective as mothers into the social sphere.

“Gilman’s immediate goal throughout her career was to end both women’s economic dependence on men and the middle-class ideal of domestic femininity.”

Edward Carpenter spoke for the larger socialism; Gilman advocated what she called the “larger motherhood.” She believed that women’s “mother instinct” could save the world and usher in utopia. As she wrote in her poem “Mother to Child,” “For the sake of my child I must hasten to save / All the children on earth from the jail and the grave.” Gilman argued that women’s motherly impulses were only waiting to be freed from the constraints of conventional domesticity and extended into society as a whole. Her life’s work centered on the concept of what she called the “World’s Mother”—the selfless, nurturing woman-spirit who loves, protects, and teaches the entire human race.

The all-embracing World’s Mother was especially attractive to Gilman given her disastrous experience within the conventional nuclear family. After the birth of her daughter in 1885, when Gilman was 24, she was plunged into a horrendous depression, an episode that she drew on for “The Yellow Wallpaper.” When her daughter was three, Gilman separated from her husband; six years later, she divorced him and gave up custody of their child. Gilman’s actions, at a time when divorce was socially abhorrent and paternal custody almost unheard of, required considerable courage. Against enormous cultural odds, she chose to live out her commitment to women’s independence. During the early years of the twentieth century, Gilman went on to write a series of utopian fictions, including Herland (1915), a witty portrait of an ideal all-female society. Her entire adult life and work can be seen as an extended utopian experiment, an effort to imagine and enact women’s transformative powers under conditions of gender equality.

![]()

Over a ten-year period, Gilman produced a remarkably large body of utopian work: three novels, a novella, and a flock of short stories. Almost all of these, like Looking Backward, place the ideal society in the future, differing from Bellamy’s novel principally in the interval required to effect the utopian transformation. Moving the Mountain (1911) is set thirty years in the future, “A Woman’s Utopia” (1907) only twenty. Both works, like the utopian short stories Gilman turned out during the same period, depend on two mechanisms to initiate radical change in a short period.

The first is the figure of the enlightened capitalist. Gilman never abandoned entirely her commitment to Bellamyite socialism, but her association with the American Fabian movement brought her into contact with socialists who made room in their vision for what now is called “social entrepreneurship”—business people who want to do well by doing good, investing money and energy into projects designed to improve society as well as to generate profit. The capitalist godfather in “A Woman’s Utopia” is conservative New Yorker Morgan Street, in love with reformer Hope Cartwright. Street, about to go traveling around the world for twenty years, leaves Cartwright and her friends $20 million to realize their cockeyed schemes. On his return, he is startled to find that they have succeeded in turning New York into a utopia by investing his money into housing complexes with kitchenless apartments, where cleaning is done by commercial services and childcare is managed by experts.54

The second utopian mechanism is religion. Both “A Woman’s Utopia” and Moving the Mountain devote extensive attention to the new religion of the future. It has no name—it’s just “Living” and “Life,” a character in “Woman’s Utopia” explains—but it is essentially the post-Christian spirituality of personal denial and service to the larger, social self that Gilman worked out as a teenager. The last news from the outside world that the narrator of Mountain hears before thirty years of isolation in Tibet is that Mary Baker Eddy had died and that “another religion had burst forth and was sweeping the country, madly taken up by the women.” Gilman had no fondness for Christian Science doctrine, but she could admire its female founder, the gender equality of its clergy, and its rapid spread during Eddy’s lifetime. Why should not her rational religion of world-service enjoy the same sort of popularity?

Between 1907 and 1913, Gilman wrote numerous variations of the same utopian blueprint: the ideal society could be achieved peacefully in a remarkably short time if only women were freed from the household to work in the world and to promote the new religion of social service. Then in 1915 she broke the mold with Herland, a fantasy that combines the plot of Tennyson’s The Princess (1847) with the conventions of the masculine adventure tale. Three chums since college—Terry, Jeff, and Van the narrator—have joined a scientific expedition to a remote part of the globe, where their native guides tell them fearsome stories of a land inhabited only by women, located at the crest of an inaccessible mountain range. Fired with desire to be the first to explore this mythic woman-land, the three men decide to return on a secret expedition of their own.

Terry, a wealthy pilot, brings along a disassembled biplane, which they put together and launch from a lake just below the mountainous cliffs that shelter the hidden women. Once in the air, they spy signs of civilization and decide to land in a remote area miles from the city they have glimpsed. The three men are armed and confident; however, the natives have told them that no man who ventured into the mountains ever returned, and the explorers advance warily—just in case.

“Gilman wrote numerous variations of the same utopian blueprint: the ideal society could be achieved peacefully in a remarkably short time if only women were freed from the household to work in the world and to promote the new religion of social service.”

The first people the three friends encounter as they explore this brave new world are three beautiful young women, who will reappear later as the men’s love interests. The volatile Alima fascinates Terry, a high-testosterone womanizer who enjoys the challenges of a difficult courtship. Jeff, a courtly southerner, is attracted to the sweet Celis, while Van forms an easy friendship with intelligent, curious Ellador. However, before the couples pair off, the men, upon their landing, first pursue the three women, intending to capture these native specimens. The athletic young women, in their sensibly reformed dress, easily outrun the men, who upon arriving at the town are surrounded by a phalanx of unarmed but well-disciplined women who capture and chloroform them.

The men wake up inside a remote fortress, where they are placed under a gentle house arrest and provided with tutors who teach them the Herland language. They try to escape but are recaptured, then are granted their liberty in exchange for a promise not to attempt another escape. At this point Van, the narrator, addresses his readers frankly: “It is no use for me to try to piece out this account with adventures. If the people who read it are not interested in these amazing women and their history, they will not be interested at all.” Van’s announcement signals a change in genre, from masculine adventure tale to utopian exposition. Fortunately, the ensuing exposition is handled gracefully. Since each of the three male protagonists has a tutor as well as a love interest, there are multiple potential expositors, thus avoiding the necessity for a Dr. Leete or Old Hammond to go on at numbing length. And the fantastic nature of Gilman’s premise seems to have liberated her from the obligation to treat at length many of the concerns of other utopian fictions, including her own earlier ventures that purported to portray an America of two or three decades hence.

Herland gives remarkably little attention to the topics that dominate earlier utopian fictions from Thomas More on, including work, the economy, and government and politics. The three female love interests work as foresters; there’s a Morrisian nod to artisans’ pride in their handicrafts; but aside from these bits of casually dropped information, the novel offers little sense of what people do for a living—or of what it means to make a living in Herland. It’s not clear how the economy is organized, how goods are produced and distributed, or how people are compensated for their labor. Herland appears to be technologically and industrially advanced—the men are transported in electric cars over an extensive system of paved roads—but in Van’s enamored descriptions, Herland’s verdant landscape is free not only of air pollution but of factories and, indeed, of the sight of any workers not engaged in agricultural pursuits. The treatment of government and politics is similarly scanty. One Herlander refers to the Land Mother—“what you call president or king”—but it is not clear how she is appointed or elected, or if elections even exist. Politics is almost certainly nonexistent. When Terry balks at the “evident unanimity” of everyone in Herland, Jeff explains that this is because women are “natural cooperators” and compares Herland to an ant colony or beehive, with each working for the good of all.

With the areas of labor, economics, government, and politics casually dismissed, Gilman felt free to explore her own idiosyncratic utopian interests, such as house pets. She devotes a section to the cats of Herland, which have been trained not to hunt birds and bred not to yowl. She gives several pages to dogs—rather, to the three men’s explanation of canines, which do not exist in Herland. The women are horrified by what they hear—nearly as horrified as a dog-loving reader of Herland is likely to be by the women’s defamiliarizing summary of what they have learned: that dogs are kept indoors as prisoners and taken out for meager exercise on a leash, are susceptible to the violent madness of rabies, and, even when healthy, are liable to bite children.

“Mothering, of every sort, is at the center of Herland society, from biological processes of conception and birth to child-rearing and education.”

Gilman’s hostility to keeping dogs as pets is linked to a larger, Carpenterian interest in animal rights. Herlanders have eliminated all domesticated animals because of the cruelty inherent in slaughtering them for food or even obtaining milk. The men’s auditors turn white as they listen to a description of “the process which robs the cow of her calf ” and beg to be excused; any interference with the natural processes of mothering is horrific to them.

Mothering, of every sort, is at the center of Herland society, from biological processes of conception and birth to child-rearing and education, from social theories of mother-love as the basis of community to religious conceptions of a universal “Mother Spirit.” The word “mother” or its variants appears over one hundred times in this brief novel—more than enough to make the hypermasculine Terry fume with exasperation. He is the first to ask outright, once the men have mastered the Herland language, “Are there no men in this country?” The answer is no: for the past two millennia the women of Herland have reproduced parthenogenetically, bearing only daughters.

Absent men, Herland society has been shaped by a communal maternalism. Women are fond of their own children, but they regard each child as the child of all. “We each have a million children to love and serve,” Van’s tutor explains to him. Gilman, keenly interested in economics, must have felt no need to explain Herland’s economic system because it seemed to her so obvious: these “natural cooperators,” whose “whole mental outlook” is collective, have no use for the individualism and competitiveness inherent in capitalism. Instead, a motherly state evidently assures every citizen’s basic needs.

This socially diffused motherliness is reinforced by Herland’s religion, a “Maternal Pantheism.” Under the gentle but pointed questioning of his sweetheart Ellador, Van is forced to admit that the “Hebrew God” of Western religions reflects the patriarchal family structure, with a father/ruler who is both loving and cruel, kind and jealous. Herlanders originally conceived of a Mother Goddess, but over their history this anthropomorphized figure has turned into an impersonal, uplifting force, the essence of mother-love “magnified beyond human limits.”

Herland served Gilman as a testing ground for ideas she would develop more fully a few years later in His Religion and Hers (1923), which locates the origins of Judeo-Christian religion in the prehistoric patriarchal past, when the human male was principally a hunter and warrior. His religious ideas were “death-based,” developed in response to men’s frequent experience of death and intended to counter their primal terror of extinction with a promise of eternal survival to the pious individual. The religion of the future, once women’s equality is achieved, will be “birthbased,” arising from women’s experience of motherhood, centered not on the individual’s survival in the afterlife but on present service to others.

Herland is, in many ways, an extended challenge to its era’s widely held conceptions of women’s essential nature. According to the gynaecocentric theory that Gilman had borrowed from Ward and elaborated over the course of her career, conventional femininity was merely a response to women’s subjection by men after the matriarchal period of human prehistory. Dependent upon men for economic survival, women developed a fascination with physical adornment, a swooning interest in heterosexual courtship, and an intense devotion to the private home and family. In Gilman’s language, they were “over-sexed,” their supposedly feminine traits developed at the expense of the human characteristics that they share with men. Freed of any reliance on men, the women of Herland aren’t “womanly,” according to Terry, which to him means that they are indifferent to his sexual swagger. The sociologically inclined Van realizes that what he has always thought of as “feminine charms” are “not feminine at all, but mere reflected masculinity—developed to please us because they had to please us.”

“Herland is, in many ways, an extended challenge to its era’s widely held conceptions of women’s essential nature.”

With no need to please men, the women of Herland are, to a certain extent, androgynous, their hair cut short, dressed in sporty leggings and tunics, capable of every physical and mental task required in an industrially advanced civilization. At the same time, Gilman insists on their differences from men—differences centered on women’s “maternal instinct.” She repeats the phrase; the novel’s entire premise depends on the idea that everything in an all-female society, from food to religion, would be shaped by women’s inherent motherly feelings.

Gilman held to her theory of women’s instinctive maternalism despite her own experiences as a mother. After Katharine’s birth, she was so overwhelmed by depression that she could not bear to hold her baby. Later, when Katharine was nine, Gilman sent the child across the country to live with her father and stepmother and then saw her only occasionally for the next six years.

Herland provided its author with a chance to reconcile the contradictions between her utopian celebration of maternal feeling and her personal experience of mothering. It turns out that although every woman in Herland is capable of giving parthenogenetic birth, only an elite is entrusted with rearing children. Collectivized and professionalized childcare was as central to Gilman’s utopian vision as the kitchenless home. Her commitment to professional childcare came in part from her conviction that women, like men, owed it to the world to work outside the home and in part from her self-exculpating belief that, as Van’s Herland tutor explains to him, the raising of children is so important to the future of the race that it must be entrusted to professionals.

Gilman derided the smallness, the possessiveness of the average woman’s conception of motherhood: my children, my family, my home. She argued for a “Wider Motherhood” with the same zeal that Edward Carpenter brought to his advocacy of the Larger Socialism. Herlanders see every child as theirs, the entire population as one family, the nation as home.

![]()

From The Last Utopians. Used with permission of Princeton University Press. Copyright © 2018 by Michael Robertson.

Michael Robertson

Michael Robertson is professor of English at The College of New Jersey and the author of two award-winning books, Worshipping Walt: The Whitman Disciples (Princeton) and Stephen Crane, Journalism, and the Making of Modern American Literature. A former freelance journalist, he has written for the New York Times, the Village Voice, Columbia Journalism Review, and many other publications.